Hughes XF-11 Prototype Reconnaissance Plane

Designed to meet the same specification as the Republic XF-12, the XF-11 was said to be scaled up from the mysterious D-2 fighter that Howard Hughes flew in secret in 1943. Resembling an enlarged P-38 Lightning, the XF-11 was optimized for the high-altitude photo-reconnaissance role. Under pressure from Congress to deliver on this project and the equally late 'Spruce Goose', Howard Hughes himself made the XF-11's first flight. Unwisely for a maiden flight, Hughes stayed up much longer. than planned - until one propeller went into reverse pitch and the XF-11 crashed into an unoccupied house in Beverly Hills. Hughes survived with head injuries, but some say he never really recovered. The second aircraft was evaluated by the USAF, who, after deciding it was twice as expensive, harder to operate and inferior to the XR-12 Rainbow, terminated the program.

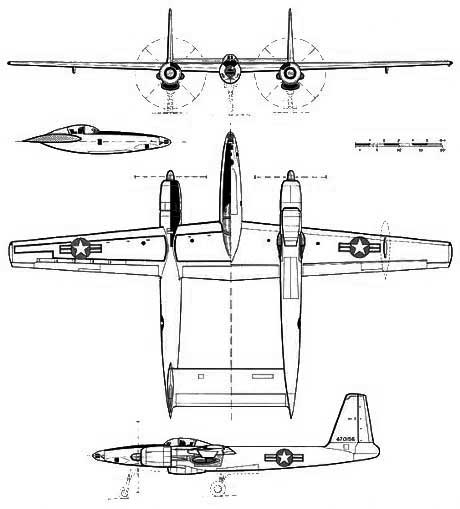

Hughes XF-11

The twin-boom Hughes XF-11 was designed in 1943 as the heaviest and fastest twin-engined aircraft in the world. Based on the Hughes D-2 wartime fighter, the XF-11 was described as 'massive and mean' by ground crew members at Hughes' California factory. The XF-11 was intended as a fast, long-range, photo-reconnaissance craft but could also have doubled as a fighter.

The twin-boom Hughes XF-11 was designed in 1943 as the heaviest and fastest twin-engined aircraft in the world. Based on the Hughes D-2 wartime fighter, the XF-11 was described as 'massive and mean' by ground crew members at Hughes' California factory. The XF-11 was intended as a fast, long-range, photo-reconnaissance craft but could also have doubled as a fighter.

The giant, shark-like XF-11 was viewed as the ideal photo platform for the anticipated 1946 invasion of Japan. When the war ended without an invasion, the future of the XF-11 became doubtful. The US Army at one point had plans to order 98 aircraft, but construction was shelved in the post-war era.

Although the first aircraft was destroyed on its only flight, the second flying version (with Curtiss-Wright propellers) was evaluated in flight tests for several years. Legend has it that Hughes masterminded the engine modifications from his hospital bed and eventually recovered sufficiently to fly the redesigned machine. The aircraft was praised for its performance - particularly its gentle stall characteristics. However, the onset of jet powered aircraft prevented the XF-11 from ever reaching production and the only flyable XF-11 was eventually scrapped.

To many people, the XF-11 was the work of a madman. Indeed, this is the reputation which the enigmatic Howard Robard Hughes took to his grave. He was a billionaire when he died in 1976, and some said he was the richest man in the world. He was also a pathological recluse who hadn't been seen in public for two decades, and some said he was stark, raving mad.

In his early years, however, Hughes was a dashing and flamboyant character. He was born rich, but he accumulated most of his fortune himself. He consorted with movie stars, started his own film company and he married glamour-girl Jane Russell. His most lasting impact, however, was in aviation. He built airplanes, and he flew airplanes. In 1938 he set a world's speed record for a flight around the world in a Lockheed Model 14 Super Electra, and a year later-as owner of TransWorld Airlines-he was responsible for nudging Lockheed down the road that would lead to the Constellation, one of the two greatest piston-engined airliners in history.

It was the airplanes that Hughes built during World War II that are seen as his greatest failures, and the factors that may very well have sowed the seeds of his madness.

The plane which would ultimately evolve into the XF-11 had its genesis in 1939 under the Hughes Aircraft experimental model designation DX-2. Hughes originally proposed it as a bomber, but the key element of his interest seems to have been the idea of constructing a large airplane by the Duramold process. This process had been developed and patented by Colonel Virginius E Clark, the Army's chief aeronautical engineer during the First World War. Duramold involved molding resin-impregnated plywood into desired shapes and contours under high heat and pressure. Pound for pound, it had been demonstrated that Duramold wooden structure had strength and rigidity comparable to metal.

In 1941, the United States was not yet involved in World War II, but the USAAF was in the midst of building up its strength in the expectation of that eventuality. Meanwhile, the DX-2 project had evolved into a large two-seat fighter design which interested the US Army Air Forces because aluminum was becoming scarce because of World War II. In October 1941, after officially scrutinizing the DX-2, the USAAF Materiel Command at Wright Field, Ohio, decided against the Hughes proposal because it couldn't quite a picture a future that involved something so archaic as wooden airplanes.

After the United States entered the war, USAAF headquarters in Washington urged the Materiel Command to reconsider the project. On 25 May 1942, the Hughes Duramold airplane was ordered under the experimental attack designation XA-37. Subsequently, the project was briefly considered for deployment as a night fighter under the experimental fighter designation XP-73. The eccentric Hughes, however, decided not to 'sell' the airplane to the USAAF until it made its first flight. This event transpired 11 months later, on 20 June 1943, with Howard Hughes at the controls. It was 43 feet long, with a wing span of 60 feet 5 inches (some sources say 66 feet), and a gross weight of 28,110 pounds. Power was supplied by two Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp 2000 hp engines.

It was estimated to have had a top speed of 433 mph, but this is unknown, because Hughes himself was the only test pilot the airplane ever knew, and the only time someone was in the cockpit with Hughes during a high-speed test flight, the the millionaire held his hand over the airspeed indicator!

The secrecy surrounding the development of the DX-2 exceeded that of a military program. All of the flying was done at a secret Hughes Aircraft facility at Harper's Dry Lake in the Mojave Desert, by Hughes himself. Furthermore, he wouldn't permit any photographs to be taken of the airplane.

The story of the Hughes DX-2 ended mysteriously on 11 November 1943 when a fire struck the hanger that contained the wooden aircraft, destroying both, along with any hope of the A-37 attack series ever coming into existence. Contemporary accounts speak of a lightning storm, while more recent recollections remember that the air was clear, and that the lightning came as a surprise. There were inevitable rumors of arson, but nothing was ever proven. There were fingers pointed at Howard Hughes, but it remains unclear what possible motive he would have had for destroying the mysterious airplane. In any case, the Materiel Command was noticeably relieved at not having to go through with buying any wooden A-37s.

In the meantime, Colonel Elliot Roosevelt, the son of the President and a friend of Hughes, had been lobbying in Washington on behalf of the project and had convinced USAAF chief General Henry H 'Hap' Arnold that a DX-2-based aircraft would make an ideal high altitude reconnaissance aircraft because of its potential speed and light weight. This line of

thinking came as the USAAF had observed-and even used the Royal Air Force's de Havilland Mosquito, a remarkable high altitude recon bird, that was made or wood. Hughes had even completed design studies for such an aircraft under his own D-5 designation.

In the meantime, Colonel Elliot Roosevelt, the son of the President and a friend of Hughes, had been lobbying in Washington on behalf of the project and had convinced USAAF chief General Henry H 'Hap' Arnold that a DX-2-based aircraft would make an ideal high altitude reconnaissance aircraft because of its potential speed and light weight. This line of

thinking came as the USAAF had observed-and even used the Royal Air Force's de Havilland Mosquito, a remarkable high altitude recon bird, that was made or wood. Hughes had even completed design studies for such an aircraft under his own D-5 designation.

Despite the continued reluctance or the Materiel Command, Hap Arnold compelled them to issue a purchase order offering in October 1943, to pay $56.6 million for 100 D-5s, which would be given the USAAF designation XF-11. Ironically, the compromise was that the XF-11 would be based on the design of the DX-2, but it would have to be metal, not wood.

It is worth noting here that the 'F' series of designations stood for 'photographic reconnaissance' prior to 1948, after which they were assigned to fighters, and the recon aircraft were given 'R for reconnaissance' prefixes. Also of importance here is that the XF-11 was the first of the series to be designed from the beginning as a high performance reconnaissance aircraft. All the others- F-1 through F-10-were modified versions of some other type of aircraft.

The contract called for the XF-11 to have a range of 5000 miles, with a top speed of 450 mph, and a first delivery date of March 1945. There were a great many teething problems inherent in the development of so unique a plane as the XF-11, but the project was proceeding reasonably well, with the first prototype being 80 percent completed, until May 1944, when 21 Hughes engineers, including the XF-11 project engineer, quit their jobs in a disagreement with their boss. From this point on, despite Hughes' promises to the contrary, the XF-11 was continuously benighted by delays and chronic labor shortages. For example, the first set of wings did not reach the Culver City, California, final production site from the subcontractor until 10 April 1945, a month after the scheduled first delivery of a completed airplane. The first of the two Pratt & Whitney R-4360 engines with their eight bladed contra-rotating propellers wasn't available until September, the month the war ended.

In the meanwhile, on 26 May 1945, the USAAF had decided to cancel 98 of the 100 XF-11 s and pay Hughes $8.6 million to complete the first two Howard Hughes was immensely displeased by this turn of events, and became obsessive about completion of the project as a means of demonstrating its validity to his detractors.

The first XF-11 was ready for taxi tests by April 1946, and on 24 April, it was flown briefly ,at an altitude of 20 feet. It was a remarkably clean airplane. With a length of 65 feet 5 inches, and a wingspan of 101 feel 5 inches, the XF-11 was nearly as big as a heavy bomber, yet it was as, sleek and trim as a fighter.

Everything went well in the early tests, except for the potentially disastrous, and unexplainable, tendency for the propellers to change pitch without warning. Thus it was that the first flight was delayed until 7 July 1946.

Again, it was Howard Hughes himself at the controls. The first flight originated at Culver City and had lasted a bit more than an hour when loss of hydraulic fluid caused the rear part of the right propeller to reverse pitch, causing severe drag and loss of lift on the right side. Hughes tried to compensate for the problem by throttling back the left engine to balance the two. He attempted an emergency landing on the Los Angeles Country Club golf course, but it went down 300 feet short, crashing into the Beverly Hills-home of Lt Col Charles Meyer, who was away in Nuremberg, Germany, serving as an interpreter at the War Crimes Trials. Both house and airplane were completely destroyed.

Hughes suffered a broken leg, multiple lacerations and a possible skull fracture. He arrived at Beverly Hills Emergency Hospital still conscious, but was given only a 50-50 chance of survival. He would, in fact, live for another 30 years, but it can be said that he never recovered.

A USAAF accident board severely chastised Hughes for his handling of the flight - for everything from failure to use the proper radio frequencies to failing to feather the right prop at the first sign of trouble. A year later, in August 1947, Hughes found himself hauled up before the Senate War Investigating Committee on charges that he and Elliot Roosevelt had used undue political influence to advance two airplanes - the XF-11 and the HK-l-that many now considered to have been expensive failures. Roosevelt countered by charging the Materiel Command with collusion with larger airplane builders in an effort to 'freeze out' smaller plane makers like Hughes.

The 1947 Senate hearings ended with findings of neither fraud nor collusion. A second XF-11 was completed in November 1947 and flight tested in 1948 with conventional propellers. A third XF-11 was reportedly under construction, but it was apparently never completed. The test program ended quietly with the multi-million dollar political football left parked on the grounds of Shepard AFB in Texas. Howard Hughes would never build another airplane, but the XF-11 and the HK-1 remain well placed in the pantheon of aviation idiosyncrasies.

Specifications for the Hughes XF-11

|

Crew: two, pilot and |

|

||

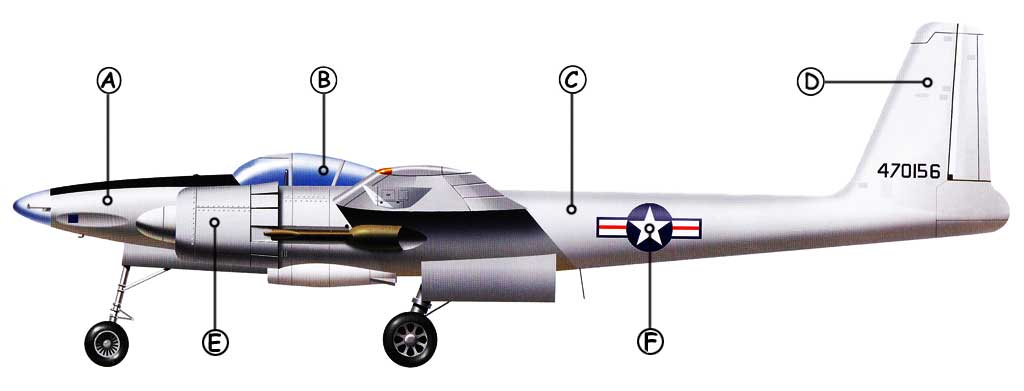

| A: The central pod housing the cockpit and camera operator's position also held the camera fit. Up to eight cameras could be carried, but they proved difficult and time consuming to load and unload. Republic's XR-12 differed from the Hughes design in having on-board photo processing facilities. | B: The F-11 was originally intended to replace the Lockheed F-5, a reconnaissance version of the the P-38 Lightning. The sudden end of World War II led to the cancellation of a production order, but the second XR-11 was nevertheless evaluated alongside the RepubliC XF-12 Rainbow. | C: In its configuration the XF-11 closely resembled the Hughes D-2 bomber and long-range fighter design which had flown in 1943. Howard Hughes was convinced that Kelly Johnson 'stole' this design for his own XP-38. |

| D: Duramold, a resin Impregnated plywood, had been used to build the D-2, but for the D-5 (XF-11) conventional aluminum construction was specified. | E: Two of Pratt & Whitney's new R-4360-31 'corn cob' Wasp Major radials powered the first XF-11. These drove eight-bladed Hamilton Standard contraprops, one of which malfunctioned causing its destruction. | F: The second XF-11 had two R-4360-37 engines powering conventional Curtiss-Wright four-bladed propellers. Fuel for these thirsty engines was held mainly in the aircraft's long tail booms. |

|

The XF-11 Crash in which Howard Hughes crashed in to a Beverly Hills home, damaging the house, destroyed the aircraft and injured himself. |