Lockheed Electra

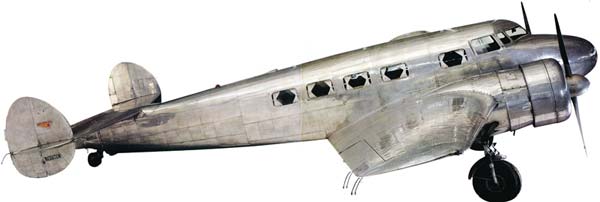

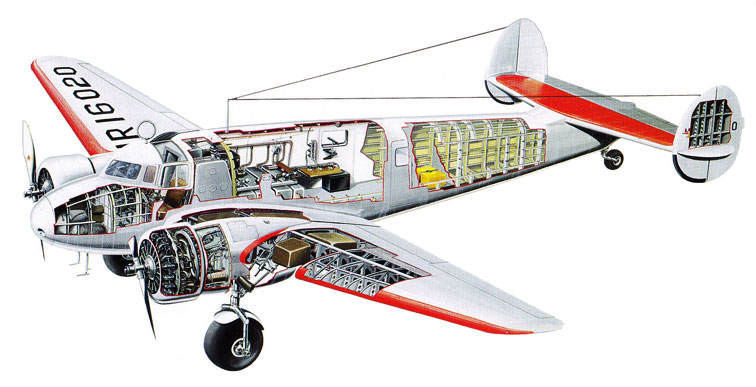

The Electra shown here was the 37th to be built. It was originally a Model 10B, powered by a pair of 420-hp Wright R-975 Whirlwind nine-cylinder radial engines. In that form it was delivered to North American Aviation (Eastern Air Lines) on September 24, 1935. It then went to Boston & Maine Airways, where it was converted to a Model 10A, with 450-hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior engines.

Lockheed Electra Amelia Earharts Record Making Twin Engine Aircraft

Lockheed Electra - Amelia Earhart

Amelia Earhart was a feminist, and well before the word became fashionable in the 1970s. She wanted to do, and could do, what most men did when they took to the air. She became an expert mechanic, she studied navigation, and she crashed airplanes and walked away from them. She owned her own plane in the roaring 1920s, and was the first woman to fly the Atlantic.

Her disappearance in the Pacific on her last trailblazing adventure is still one of the unexplained aviation mysteries of the twentieth century. It was quite a record for a girl born in the American town of Atchison, Kansas in 1897. Amelia later said she had seen her first plane at the age of 10 at the Iowa State fair “a thing of rusty wire and wood I was much more interested in an absurd hat I had just purchased for 15 cents.”

Amelia took her first joyride at the age of 23. Within weeks she was taking flying lessons. She was not a “natural” but her teacher, John Montijo, a tough ex-army man, who had taken over from Amelia's’ first instructor, Nita Snook, taught her well and made her do stunt-flying before he would her to fly solo. Amelia decided to buy her own plane, an underpowered Kinner biplane which she painted yellow and called The Canary.

In 1928, now living in Boston, Amelia was chosen by a publisher of adventure books to fly a Fokker Tri motor across the Atlantic. By now used to being in command of her own plane, this time she would be, in fact, a passenger but with a pilot’s understanding of the dangers. The plane was to be piloted by Bill Stultz, a superb 28-year-old flier and Lou Gordon, flight mechanic. The aircraft, named Friendship, was previously owned by Commander Byrd and was fitted with pontoons (floats), for alighting on water.

First they flew the Friendship from Boston to Trepassy, Newfoundland, and there, on Sunday June 17 they tried to take off. Having twice failed to lift from the water, they made a desperate decision. They dumped fuel, reducing from 830 gallons to 700 gallons which, even with favorable forecast tail winds, left little margin for error. Eventually, after a three-mile takeoff run, they clawed their way into the air. One engine, saturated with spray, took nearly an hour to build to full power. The time was 2:15 p.m., British summer time.

They battled throughout the night, flying in fog by instruments. Then the radio gave up. At 8:00 a.m. they passed ships sailing below. Later, with clouds down to 500 feet they saw a small fleet of fishing vessels, and about an hour after that, uncertain of their position, they saw through the mists what they thought to be Ireland. Stultz brought the Friendship down and tied up to a buoy. They had about 50 gallons of fuel left - it would not feed the carburetors for long.

The trio was not in Ireland, but at Burry Port in South Wales. They had landed at 12:40 p.m. after a flight of 20 hours, 49 minutes. Nobody came to meet them.

Although the people waved at them from the shore, it was a not for nearly an hour after alighting that some men came out in a boat to investigate. The next day they fueled up and flew on to Southampton where they were greeted enthusiastically by surging crowds of people, reporters, and newsreel cameramen.

Overnight, Amelia Earhart was transformed into an international celebrity. She became one of the best-known and respected American women, an icon for every woman who wanted to take her place as an individual in a fast changing world. After the success of the Friendship flight, Amelia took up competitive flying and set several records. Her main objective was to help promote flying as a safe means of transportation and, always a competitive person, she also wanted to keep her name in the news.

On may 20, 1932, Amelia set out from Harbor Grace, in Newfoundland, to fly solo across the Atlantic to Paris. Her aircraft was a Lockheed Vega, bought in 1929 and modified with extra fuel tanks and a new 500-horsepower supercharged Pratt & Whitney Wasp engine. She had spent months gaining experience with instrument flying - necessary for night flying and to cope with cloud and heavy fog expected to be encountered during her flight. Though she suffered mechanical troubles - the altimeter failed so she couldn't be accurate about her true height and the exhaust manifold split causing engine vibration which worsened as the hours went by - Amelia flew on. At one point, with the wings iced up, the Vega went into a spin and when she switched to her reserve fuel tank, petrol began to leak into the cockpit which, combined with the exhaust flames from split exhaust, caused her considerable tension.

As soon as she saw land, she searched for a suitable landing place, coming down gracefully in a long, sloping meadow. A lone, astonished farmer was the only observer. Amelia cut the engine, and climbed out of the Vega. “where am I?” she asked. “In Gallagher’s pasture!” he replied.

She had flown 2,026 miles in 14 hours, 54 minutes and had landed in Culmore, near Londonderry, Northern Ireland. In doing so, she carved a record, for having flown the Atlantic in the shortest time in either direction. And she had cemented her reputation as the world’s most accomplished woman pilot.

On June 1, 1937, with her trusted navigator Fred Noonan, Amelia Earhart took off from Miami in her silver and red Lockheed Electra to fly around the world on an equatorial route. “I want to flight right around the middle of the world,” she said. Noonan was in his forties with a reputation as one of the world’s top aerial navigators. He had served with the British Navy in World War I, then studied aerial navigation at the Weems School of Navigation at Annapolis before working for Pan-Am as a navigation instructor.

On June 1, 1937, with her trusted navigator Fred Noonan, Amelia Earhart took off from Miami in her silver and red Lockheed Electra to fly around the world on an equatorial route. “I want to flight right around the middle of the world,” she said. Noonan was in his forties with a reputation as one of the world’s top aerial navigators. He had served with the British Navy in World War I, then studied aerial navigation at the Weems School of Navigation at Annapolis before working for Pan-Am as a navigation instructor.

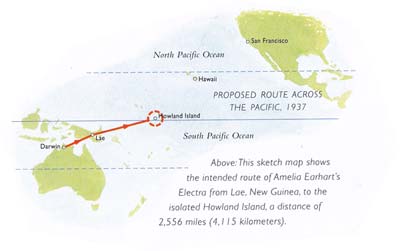

With the Electra fitted with the latest in communication and navigational aids, plus a Sperry autopilot to help on the long hops, they moved effectively from Miami to Puerto Rico, then on to Brazil, across the Atlantic to Africa, to the Mediterranean, Pakistan, India, Burma (now Myanmar), Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, to Darwin, Australia, and then to Lae in Papua New Guinea. The next leg was the longest. They would fly to Howland Island, a distance of 2,556 miles.

With a heavy load of fuel, Amelia lined up on the runway and at precisely 00:00 GMT (10:30 a.m. Lae time) started her takeoff. There was no wind and observers reported that the plane lumbered along, only becoming airborne at the very end of the runway which dropped 25 feet into the sea, and that the Electra was flying so low over the water that the propellers were throwing spray.

Amelia kept in touch with Lae by radio until she flew out of range. From then on, radio contact with the coast guard vessel, Itasca, became increasingly confused. The ship’s radio officers began to get faint messages from Amelia, but it appeared she was not receiving theirs. Eventually, after 18 hours of flying, they began to get strong signals from the Electra, but again, no indication whether their replies were getting through.

vessel, Itasca, became increasingly confused. The ship’s radio officers began to get faint messages from Amelia, but it appeared she was not receiving theirs. Eventually, after 18 hours of flying, they began to get strong signals from the Electra, but again, no indication whether their replies were getting through.

Then some ominous words from Amelia:b ”We must be on you but cannot see you but gas is running low. Been unable to reach you on my radio.” At 18:50 GMT, briefly, Amelia and Itasca were in two-way communication. Responding to the message: ”Itasca to K.H.A.Q.Q. Go ahead on 3,105 or 500 cycles,” Amelia radioed: ”K.H.A.Q.Q. calling Itasca. We received your signals but unable to get a minimum. Pleas take a bearing on us and answer 3,105 with voice.”

The ship kept trying to contact the Electra again, to tell them the radio signals had been to poor for them to get a reading. Then at 20:14 GMT, Amelia’s voice was heard for the last time in a hurried, almost incoherent call. “K.H.A.Q.Q. to Itasca. We are on line position 175 dash 337, will repeat this message on 6,210 kilocycles. We are running north and south.”

That was the last anyone heard from Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan.

Lockheed Electra

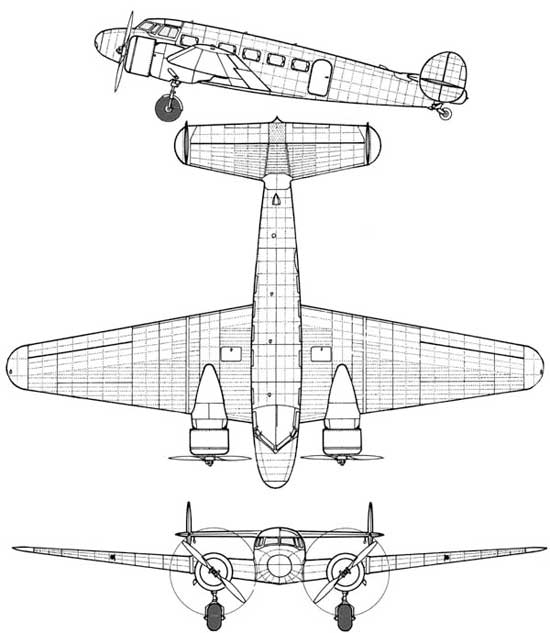

In an attempt to keep pace with Boeing and Douglas in the lucrative twin-engine airliner market, Lockheed introduced an elegant ten-twelve seater called the electra in 1935. Easily recognizable with its twin tail fins, the Electra had a neat retractable undercarriage and a useful maximum speed of 200 mph. It was something of a challenge to Lockheed to build such an aircraft, as it was constructed entirely of metal, whereas their previous products had been wooden machines like the bullet-shaped Vega. That neat retractable undercarriage mechanism almost became the prototype's downfall when it failed to lock down properly after an early test flight. The pilot just managed to maintain control as the Electra touched down on the runway and the fault was rectified before mass production began.

Electras could carry the same number of passengers as Boeing 247s, but in doing so could fly faster, higher, and further. At $36,00 they were also the cheapest planes in that sector of the market, and so proved highly competitive. Electras went on to server with such famous airlines as Baniff and Pan American and were also ordered by operators in Britain, Australia and New Zealand. Both Northwest Airlines and Pan American had ordered it before its maiden flight, and the former company put it into service the following August. In all, 149 were built, serving around the world.

Electras could carry the same number of passengers as Boeing 247s, but in doing so could fly faster, higher, and further. At $36,00 they were also the cheapest planes in that sector of the market, and so proved highly competitive. Electras went on to server with such famous airlines as Baniff and Pan American and were also ordered by operators in Britain, Australia and New Zealand. Both Northwest Airlines and Pan American had ordered it before its maiden flight, and the former company put it into service the following August. In all, 149 were built, serving around the world.

Built entirely of a light alloy, the Electra had a monocoque fuselage and cantilever wings, making it light yet strong, and free from the drag inducing struts and bracing wires of many of the earlier-generation airliners. As aircraft like this entered service, speed became more important than previously in the airlines' fight for customers.

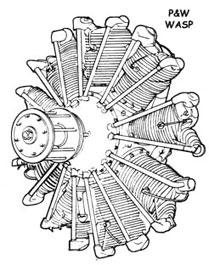

The Electra powerplant was a nine-cylinder engine, the Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior had a diameter of 451 in and weighed 596 lb. With a takeoff rating of 450 hp at 2,300 rpm, and driving Hamilton-Standard controllable-pitch, two-bladed metal propellers, it gave the Electra a top speed at sea level of 190 mph.

Specifications

|

Crew: 2

|

|

|

The Electra powerplant was a nine-cylinder engine, the Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior had a diameter of 451 in and weighed 596 lb. With a takeoff rating of 450 hp at 2,300 rpm, and driving Hamilton-Standard controllable-pitch, two-bladed metal propellers, it gave the Electra a topspeed at sea level of 190 mph. |

|

|

Cutaway of the Amelia Earhart's Lockheed Electra. |