Boeing (Model 200 & 221) Monomail

In 1930 Boeing produced the Model 200 Monomail, the most advanced mailplane yet built. It was the first American plane to use a circular-section fuselage of metal monocoque construction, a neatly cowled radial engine offering good power and reliability with low fuel consumption....

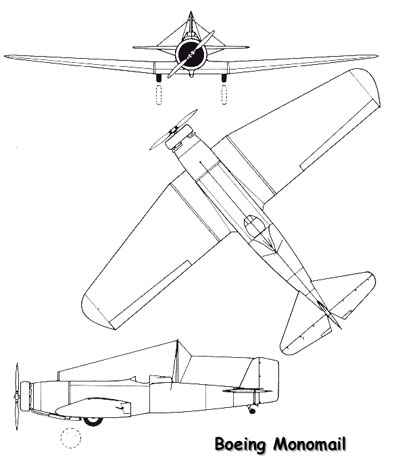

Boeing Monomail

In 1927 Boeing, soon to emerge as a giant of the aeronautical world, made an

extremely low tender for the Chicago to San Francisco route and managed to make a

profit on the contract using aircraft of its own design. The type was the Model 404, for its

time a remarkably efficient and economical airplane, designed as a very clean machine

whose low drag was enhanced by subtle design details and the reduction of structural

weight. The age of World War I aircraft and their derivatives was finally ending.

In 1927 Boeing, soon to emerge as a giant of the aeronautical world, made an

extremely low tender for the Chicago to San Francisco route and managed to make a

profit on the contract using aircraft of its own design. The type was the Model 404, for its

time a remarkably efficient and economical airplane, designed as a very clean machine

whose low drag was enhanced by subtle design details and the reduction of structural

weight. The age of World War I aircraft and their derivatives was finally ending.

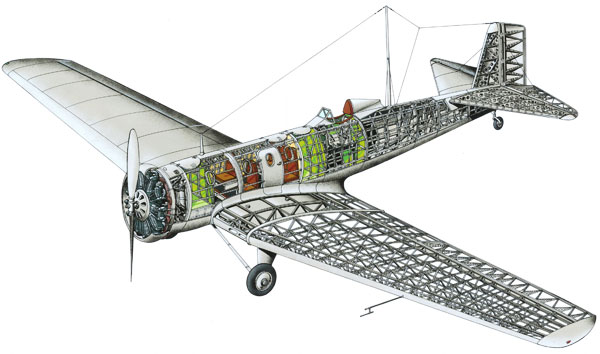

In 1930 Boeing produced the Model 200 Monomail, the most advanced mailplane yet built. It was the first American plane to use a circular-section fuselage of metal monocoque construction, a neatly cowled radial engine offering good power and reliability with low fuel consumption, a cantilever low-set wing of metal stressed-skin construction, and retractable landing gear. The Monomail was a revelation, for its full use of stressed-skin metal was both practical and beautiful.

A year later Boeing used the same design formula at a larger, twin-engined size, to produce a bomber. This was the B-9, the immediate predecessor of the first truly modern airliner, the Model 247, in 1932. The Model 247 was a remarkable airplane, and perhaps deserved to enjoy greater commercial success than it did. Powered by a pair of 550-hp (410-kW) Pratt & Whitney Wasp radial engines inside clean wing-mounted nacelles, the all-metal Model 247 was based on stressed-skin and semi-monocoque construction with an oval fuselage, enclosed cockpit as well as accommodation, and main landing-gear units that retracted into the engine nacelles. To improve the safety factor at high altitude, rubber deicing "boots" were fitted to the wings and tail surfaces. The air- plane's one limiting factor was that it was just slightly too small, with capacity for only 10 passengers at a time when the airlines were just beginning to look for something larger.

The Model 247 entered service with United Air Lines, formed in 1934 from Boeing Air Transport and two other companies, and did much to make this new giant airline a major force in American air transport. Other major American airlines already in existence were Pan-American Airlines, founded in1927, and Transcontinental and Western Air, otherwise known as TWA (today the letters stand for Trans World Airlines), founded in 1930 through an amalgamation of four smaller airlines. Not to be outdone by United Air Lines Mode1 247 fleet, TWA asked Douglas to produce a similar but superior machine.

AIRMAIL

|

| Pilot George Boyle looks pensive shortly before taking off with a load of airmail on May 15, 1918. That map that a friend is affixing to the flyer's leg was of little use, since Boyle steered his airplane in the wrong direction soon after take-off. |

It wouldn't have taken an astrologer

to persuade the United States Post

Office in 1918 that the stars had conspired

against it. The department's

decision to carry American airmail in

its own planes appeared doomed

from the beginning, and if postal officials

had been more superstitious

they might have spared themselves

some embarrassment. The trouble

started when the first edition of the

new twenty-four-cent airmail stamps

came off the press with an ominous

misprint: several sheets of the commemorative

stamps were printed with

the artwork inverted, so that they

seemed to portray a Post Office

airplane flying along peacefully upside

down, and a lucky collector

managed to buy a sheet of them

before

anyone noticed the mistake.

The situation worsened on May 15, the scheduled date for what was supposed to be the maiden flight over a route connecting Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and New York. The takeoff was delayed for about thirty minutes because the pilot couldn't seem to get his engine to turn over. Eventually someone noticed that there was no gas in the airplane's fuel tank. The plane finally took off, and the audience, which included an impatient President Wilson, breathed a sigh of relief that was cut short when it was discovered that the pilot was flying in the wrong direction. He ended up about twenty-five miles south of Washington, in Waldorf, Maryland, and his load of mail had to be shipped to its destinations by train.

The Post Office's luck changed somewhat in the years that followed, but its flight record was more than occasionally marred by mishap and even tragedy. Thirty-one of the department's first forty pilots had been killed by 1925, the year private airlines took over airmail contracts. In the words of Dean Smith, an early Post Office flier, "the airmail was considered pretty much a suicide club, and only pilots desperate to fly would join it."

Passage in 1925 of the Kelly Bill, a piece of legislation designed to promote commercial aviation, authorized the transfer of airmail routes to private airlines, and the terms were so profitable that the government received an overwhelming number of applications, many of them from companies formed on the spur of the moment. The Kelly Bill was followed by the Air Commerce Act of 1926, the first legislation in this country pertaining to civil aviation. By the end of September 1927, domestic airmail routes were handled exclusively by private airlines, and commercial aviation had been given a much-needed boost.

|

Charles Lindbergh at the controls of one of

the planes that flew American airmail in the

first years after the service's inception. |

Designer:

C. N. "Monty" Montieth

|

Monty Montieth, leaning on the wing of a Boeing 247, explains a set of engineering drawing. |

Charles N. "Monty" Montieth was Boeing's first nationally recognized chief engineer. A big man in stature, he was a larger-than-life character in other ways as well, he played halfback at Washington University in St. Louis, became a World War I pilot and flying instructor, and graduated in engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology after the war. He could draw and paint, play several musical instruments, and was considered an expert photographer.

In 1922 Montieth was an Army Air Service procurement officer at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio. A number of America's outstanding early aero-engineering minds were there at the time, including Maj. Reuben Fleet, the future founder of Consolidated Aircraft. Montieth may have been the best of a talented lot, having become chief of the Airplane Section of McCook's Engineering Division two years alter leaving Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He had written the Army's standard textbook on aeronautical engineering, Simple Aerodynamics and the Airplane. He also spent three years on the aerodynamics subcommittee of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics.

His rapid rise continued after, he came to work for Boeing in 1925. He was chief engineer 1927 and a vice president in 1934.

Montieth designed two important Boeing types: the Boeing 80 in late 1927 and the P-96A fighter in late 1931. Both were characteristic of Montieth's design philosophy, i.e., strong, conservative, safe. Although the P-26A was the first monoplane fighter to enter service in the United States, it also had such dated features as wire-braced wings, an open cockpit, and fixed, spatted landing gear. Montieth had watched a buddy die at Kelly Field, Texas, when the wings sheared off his trainer, and the experience had made him wary of innovation.

Younger engineers, headed by Bob Minshall, designed the Model 200 Monomail, Boeing's first truly innovative design. At Montieth's insistence, it was laid out in both monoplane and biplane forms until the advantages of the monoplane's reduced drag became obvious to both teams.

Montieth was visibly horrified to see a veteran airmail pilot named Slim Lewis loop the Monomail three consecutive times for the sheer joy of it during an early flight test. Harold Mansfield describes Montieth waving his fists at the sky in frustration. Aside from popping some wing- root rivets, the Monomail suffered no structural damage, much to Montieth's surprise. He also had his reservations about the experimental variable-pitch propeller that Hamilton Standard tested on the Monomail to help take advantage of its aerodynamic slickness.

In 1932 Montieth was still insisting on alternative biplane or braced high-wing configuration schemes lot what became the first American low-wing monoplane air- liner, the Boeing 247 . Later, he found the big wing flaps young Ed Wells was designing for the B-17 awfully daring and suggested he leave them off. Monty Montieth, the avuncular, pipe-smoking Renaissance man, found himself being left behind by the breathtaking pace of aviation progress during the mid-thirties.

Yet it was Montieth who had recruited and developed the generation of engineers who took Boeing to the forefront of four-engine airplane development. His was a consistent voice for safety in a company whose name was becoming synonymous with safe airplanes.

Montieth was forced to retire from Boeing in 1938 because of failing eyesight. Despondent, according to his wife, at the prospect of going blind, the consequence of the strain of writing his textbook on aeronautics, Montieth shot himself on March 17, 1940. He was forty-eight.

|

Away from the drawing board, former halfback Monty Montieth unload the front mail compartment. |

|

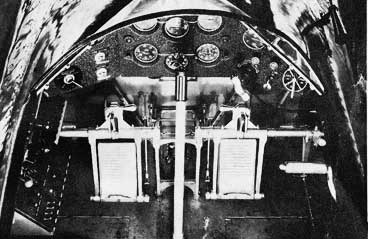

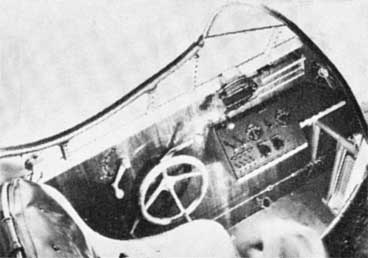

Cockpit of the Boeing Monomail. |

|

| Left side of the cockpit showing the stabilizer trim wheel, and throttle controls. |

|

| Ride side of the cockpit shows the landing gear retraction handle center, and two smaller handles that are the independent locking handles for each landing gear. |

Specifications for the Boeing Model 221

|

Crew: 1 Capacity: 6 Length: 59 ft 1 in Wingspan: 41 ft 10 in Max takeoff weight: 8,000 lb Powerplant: 1× Pratt & Whitney Hornet B, 575 hp Performance Maximum speed: 158 mph Cruise speed: 135 mph Range: 575 mi Service ceiling: 14,700 ft |

|

| These are all that can be found of a Boeing 221 Monomail crash. For more information about this crash. |