Lindbergh and the Spirit of St Louis

The most celebrated aeroplane designed by Ryan, the single engine NYP (better known as the Spirit of St Louis) was the plane in which Charles Lindbergh achieved the first solo nonstop crossing of the Atlantic when he flew from New York to Paris in 1927.

Unlike some famous aviators, Lindbergh's feats did not end with just this one flight later he went on to fly from the US to Tokyo over the Arctic with his wife Anne Marrow Lindbergh in a Lockheed Sirius.

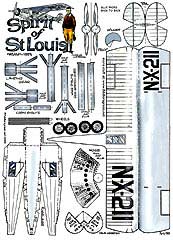

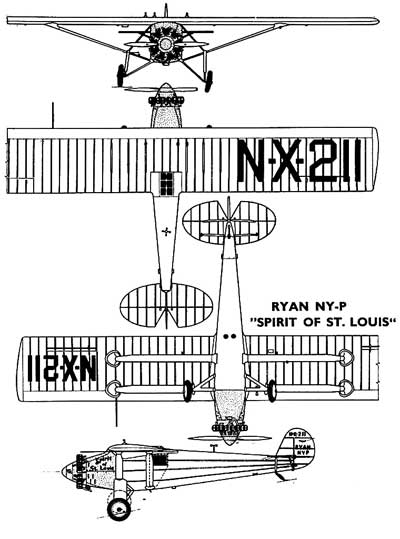

Ryan - Spirit of St. Louis

The "Spirit of St. Louis" was designed by Donald

Hall under the direct supervision of Charles Lindbergh.

The "Spirit of St. Louis" was designed by Donald

Hall under the direct supervision of Charles Lindbergh.

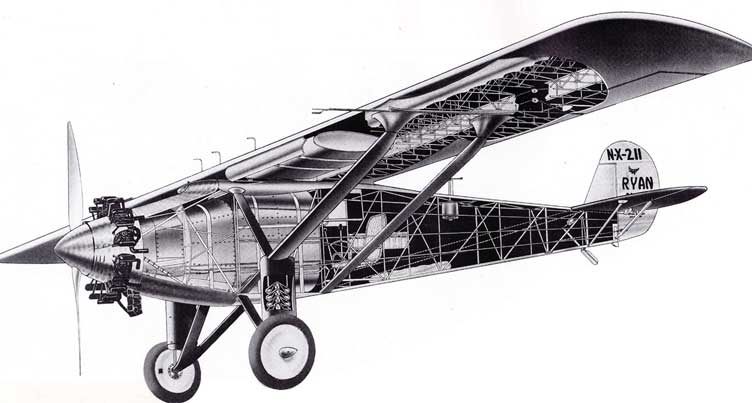

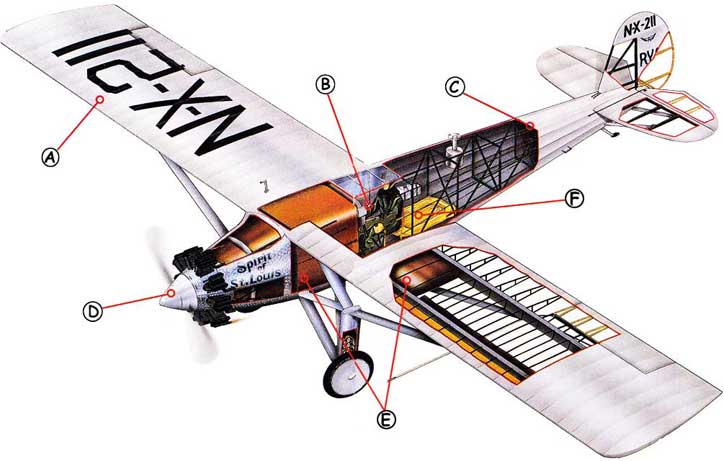

It is a highly modified version of a conventional Ryan M-2 strut-braced monoplane, powered by a reliable Wright J-5C engine. Because the fuel tanks were located ahead of the cockpit for safety in case of an accident, Lindbergh could not see directly ahead, except by using a periscope on the left side or by turning the airplane and looking out a side window. The two tubes beneath the fuselage are flare dispensers that were installed for Lindbergh's flights to Latin America and the Caribbean.

The Ryan Aircraft Corporation's Spirit of St. Louis is perhaps one of the most famous aircraft ever built. With Charles Lindbergh as pilot, it became the first aircraft to successfully fly across the Atlantic Ocean in May 1927. Its marathon 33-hour, nonstop, non refueled flight departed Roosevelt Field on Long Island, New York and when the plane landed at LeBourget Airport in Paris, France, Lindbergh became an international hero overnight.

The Spirit of St. Louis was enshrined in the Smithsonian Institution's National Air & Space Museum, alongside the Wright Brothers' aircraft. "Spirit of St. Louis" was named in honor of Lindbergh's supporters in St. Louis, Missouri, who paid for the aircraft. "NYP" is an acronym for "New York-Paris."

Dividing the Old World from the New, the Atlantic Ocean has always been a barrier to trade between Europe and the Americas, and the commercial importance of an aerial link was realized long before it became a practical possibility.

A flurry of activity in 1919 proved that the Atlantic could be conquered, but many years were to pass before it was tamed; the pioneer flights of Read (first crossing), Alcock and Brown (first non-stop crossing) and Scott (first crossings by airship) were a far cry from commercial operations which could offer the required degree of reliability with an economic payload.

During the 'twenties and 'thirties, many ingenious solutions were advanced to the problem of crossing 2,000 miles of water, frequently in adverse wind and weather and with inadequate navigational aids.

The route across the South Atlantic was a little easier than that farther north. From Dakar, in Senegal, to Natal, in Brazil, the distance was just under 1,900 miles , the weather was usually good and, in an emergency, the island of Fernando de Noronha, 300 miles off the Brazilian coast, could be used for refueling. The enterprise of French and German pioneers led to the establishment of air routes across the South Atlantic within a decade of the first Atlantic crossings-but not before the North Atlantic had witnessed another epic flight which, in public acclaim, outdid even the achievement of Alcock and Brown.

Spirit-of-St Louis-First Crossing:

The first Atlantic crossings had, not unnaturally, been concerned

with little more than getting an aeroplane and its crew across

the shortest distance of water separating Europe and America.

It was not long, however, before attention was turned to linking

centers of population further inland, and as early as 1920 a prize

of $25,000 had been offered for the first non-stop flight between

Paris and New York (in either direction).

The first Atlantic crossings had, not unnaturally, been concerned

with little more than getting an aeroplane and its crew across

the shortest distance of water separating Europe and America.

It was not long, however, before attention was turned to linking

centers of population further inland, and as early as 1920 a prize

of $25,000 had been offered for the first non-stop flight between

Paris and New York (in either direction).

The first attempt to cross the Atlantic from east to west, against the prevailing westerly winds, was made in 1924, when three Douglas Cruisers left Brough, in Yorkshire, and two succeeded in reaching Labrador in stages, with lengthy intervening stops. Further attempts in each direction during 1927 took the lives of the Americans Davis and Wooster, the Frenchmen Nungesser and Coli, and two crew members of the Frenchman Fonck. Then, with little prior publicity, the young American Charles Lindbergh arrived in Paris on May 21, 1927, at the end of a 332-hour, 3,610-mile flight from New York. His was the first non-stop solo flight, and the longest trans Atlantic fight to that date, qualifying for the 525,000 prize and resulting in a display of public adulation which today is more usually reserved for pop-stars.

Lindbergh, 25 years of age and a pilot by profession, had a natural flair for flying and above-average ability as a navigator. He needed both in good measure through the long watches of the moonless night over the Atlantic, as he battled through icing levels, unknown winds and poor visibility.

His flight not only demonstrated great personal skill and courage, but also vindicated his faith in the single 237 hp Wright Whirlwind engine which powered the specially-built Ryan NYP (New York-Paris) monoplane Spirit of St Louis.

Apart from the engine and rudimentary cockpit, from which the only forward view could be obtained through a periscope, the NYP was little more than a flying fuel tank, containing 450 US gallons in the fuselage and wings. Like most other Atlantic fliers of the period, Lindbergh made his take-off with the aeroplane loaded to a weight far above normal; the ability of the aeroplane to leave the ground at this weight in the length of runway available was unknown until the start of the flight.

After a hazardous but successful take-off, Lindbergh flew north from Long Island to cross Newfoundland before setting course eastwards. His landfall, 28 hours after take-off, was only three miles off course over the Irish coast, and the remainder of the flight, across the tip of Cornwall and on to Cherbourg and Paris, was uneventful.

Less than a lifetime ago it was widely believed that non-stop transatlantic flight was impossible. In 1921, Charles Lindbergh's historic flight in his Spirit of St. Louis changed the mind set of the world. His courage, careful planning and devotion to his mission ultimately led him to success. Lindbergh passed away in 1974, but the impact of his flight will be long remembered as one of the greatest achievements of mankind. The Spirit of St. Louis now hangs in the "Milestones of Flight" hall in the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum, where it has been on exhibit since 1976.

The Spirit was based on a successful mail-carrying monoplane that the company had in production at the time called the Ryan M-1. Lindbergh worked with Ryan's design engineer Donald Hall to redesign the M-1 to make it capable of the long flight. 850 hours were spent reengineering the M-1. The original Spirit was built in just 60 days with the staff of the Ryan Airlines company working around the clock for a total of 3000 man-hours. The company saved a considerable amount of time by utilizing many components from the M- 1 including the tail surfaces, wing ribs and many other parts and sub-assemblies. Three fuel tanks were installed in the wings and because of the extra weight of fuel required to complete the flight, the wingspan was extended to 46' from 36' for additional lift. The Spirit weighed 2150lbs. empty. Fully loaded with 450 gallons of gasoline, 25 gallons of oil, minimal supplies and Lindbergh himself, the gross weight totaled 5250 lbs. The gasoline itself weighed 2150lbs., 600 lbs more than the aircraft itself! After completing the 3,600-mile flight, Lindbergh had 85 gallons of gas remaining in his tanks.

The M-1 fuselage design was lengthened and its shape was modified to provide Lindbergh with an enclosed cabin as opposed to an open cockpit. Lindbergh did not want to sit between the engine and the tanks, so two additional tanks were placed in front of him between the engine and the cabin. The tanks blocked Lindbergh's forward view, so his instrument panel (located just behind the main tank) was equipped with a small periscope. The periscope projected out of the left side of the fuselage and provided him with slightly improved visibility. He used the device when flying near the coast to avoid hitting tall masts of sailing vessels. Other times he would peer out of the cockpit window cutouts in the side of the fuselage to see the outside world. These cutouts had removable windows that could easily be installed to keep the cold wind out of the cabin.

The late Frank Tallman (famed motion-picture stunt pilot and early aircraft collector) built a copy of the Spirit of St. Louis for the 1957 movie of the same name starring Jimmy Stewart. Tallman later recorded many of his flying experiences in his popular book, Flying the Old Planes. In reference to flying the Spirit without being able to see forward he wrote, "strangely enough, the lack of adequate forward visibility doesn't bother me too much." It is not readily apparent unless you are in the pilot's seat, but most vintage biplanes have very poor forward visibility, especially while on the ground with the tail down while taxiing, taking-off or landing. In comparison with a biplane the Spirit actually has better downward and outward visibility as there are no lower wings to block the pilot's view.

Lindbergh amassed a total of just under 490 hours on the airplane, completing 174 flights before donating it to the National Air Museum in Washington, DC in April of 1928. He carried only a handful of passengers aloft in the Spirit including his mother, Donald Hall, Edsel Ford and Henry Ford. The Spirit landed in each of the 48 states (at the time there were only 48 states), stopped at the islands of the West Indies, and flew all through Central and South America. Lindbergh flew in and out of airfields of all shapes and sizes, attesting to the design of the aircraft. It is said by some to have been a "dog" to fly, but Lindbergh flew an additional 400+ hours after his Atlantic crossing without making any modifications to alter its performance.

|

Ryan NYP "Spirit of St. Louis"replica is at Fantasy of Flight in Polk City,Florida |

|

|

|

|

|

Transporting the Ryan- Spirit of St Louis - in Paris |

|

Before take off from Roosevelt field, a little word from our sponsor  |

Dick Doll works a little misty morning diorama magic with his FG model of the Spirit of St Louis waiting at the far end of Roosevelt Field. |

|

-paper-model.jpg) |

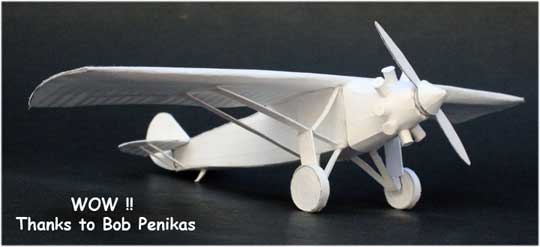

Subject: MY First INSIDE OUT FG. What to build? Looking through the FG website models what would be most recognizable as an all white build? Spirit Of St. Louis! Even non aviator types know this one. Printed the Fiddlersgreen Black & White parts page on Wausau Exact Vellum Bristol 57LB. It appears the solid black wing registration numbers would show through from the back side so I photoshopped out all the markings. Photo attached. Scored all wing ribs, fuselage windows, doors, and stringers. Photo attached. Wrapped scrap around skewer to form cylinders.(see photo above) The Instruction sheet three view in deep black is difficult to see any detail; guessed at tail struts. I will do some Internet research and make any corrections.. Bob Penikas |

|

|

The Ryan was well equipped for its day with most of the basic flight and engine instruments. |

Specifications for the Ryan Spirit of St. Louis

|

Length: 27 ft 7 in Wingspan: 46 ft Height: 9 ft 10 in Wing area: 320 ft² Airfoil: Clark Y Empty weight: 2,150 lb Loaded weight: 2,888 lb Useful load: 450 gal Max takeoff weight: 5,135 lb Powerplant: 1× Wright Whirlwind J-5C Single blade Standard Steel Propeller, 223 hp Performance Maximum speed: 133 mph Cruise speed: 100- 110 mph Range: 4,100 mi Service ceiling: 16,400 ft Wing loading: 16 lb/ft² Power/mass: 23 lb/hp |

|

||

| A: The Ryan was a fairly conventional high-wing monoplane. The wings were steel tube covered in fabric, while the ailerons, elevators and rudder were fabric-covered wood. | B: Lindbergh knew he was going to be over the North Atlantic for more than a day, so he wore a thick fleece-lined flying suit, Even so, as fatigue set in he began to feel the cold. | C: The fuselage, like the wings, was of fabric-covered steel tube. The fabric was heavy cotton treated with cellulose solution and painted in aluminum paint. |

| D: Power came from a Wright Whirlwind engine, a reliable and well-tried powerplant. lt was a nine-cylinder radial capable of delivering more than 230 hp. | E: Most of the front fuselage was taken up by fuel tanks, which, together with wing tanks, held 450 gallons of aviation fuel. The Spirit of St. Louis used 366 gallons during the flight. | F: Lindbergh sat in a lightweight wicker seat. Survival equipment was kept to a minimum: a small dinghy, maps, charts, a hunting knife and fishing tackle. For sustenance en route he carried five ham sandwiches and two canteens of water. |