Boeing F4B/P-12

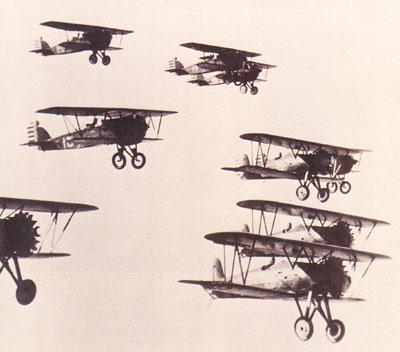

Serving the US Navy at the end of the biplane era, the classic F4B was the star of the family of famous Boeing fighters which included the US Army Air Corps' P-12 and the export Model 100. The F4B was a super ship to fly and was the most capable carrier-based fighter of its time. For all its elegance and maneuverability, the F4B triumphed successfully for only a brief time before being eclipsed by the arrival of the monoplane in the late 1930s.

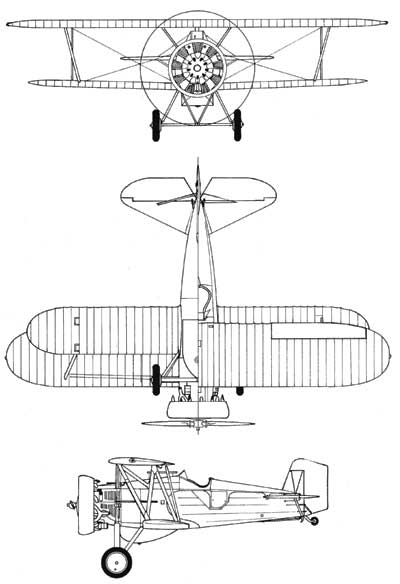

Boeing F4B (P-12)

The first production model, the F4B-1, flew in May 1929. Developed from the original self-funded Boeing prototypes, twenty-seven models were ordered with a split landing gear,like the kind used on the Model 89. The landing gear configuration was split so it could accommodate a bomb between the aircraft's wheels an important design distinction, since the Navy used its fighting aircraft for pursuit and dive-bombing. The first F4B-1s served on board the USS Lexington and the USS Langle), two of the Navy's first aircraft carriers. Later, existing F4B-1s were modified with innovations from later variants and served as Navy trainers.

The next modification, the F4B-2, favored the Model 83's pivoting cross- axle landing gear with "V" struts and bracing. This version incorporated a swiveling tailwheel and provisions for flotation, two beneficial features for a carrier-based aircraft. In all, forty-six F4B-2s were built and delivered by May 1931. This F4B closely resembled the P-12C, but the Navy's F4B-2 was built as a fighter-bomber. Unlike the P-12C, the F4B-2 had the capacity to carry 116 pounds of external stores.

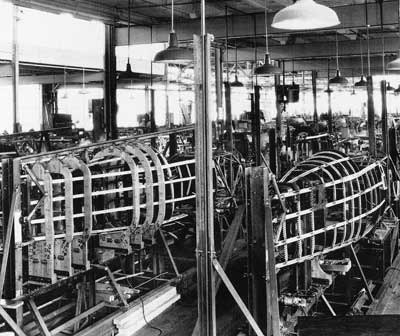

Having already modified the F4B twice, Boeing came to a design cross- roads. The company decided not to cover the next F4B variants with fabric. Instead, a semimonocoque covering made of duralumin paneling was used to significantly enhance aerodynamic performance and lengthen the service and maintenance life of each aircraft. Duralumin was already used to cover the control surfaces; using the material more extensively was a logical evolutionary progression. At first, engineers were concerned about the additional weight involved in replacing fabric with metal, but the all-metal F4Bs did not experience performance degradation as compared to their older fabric-covered models. Other enhancements and design evolutions kept pace with airframe improvements, thereby negating any weight issues.

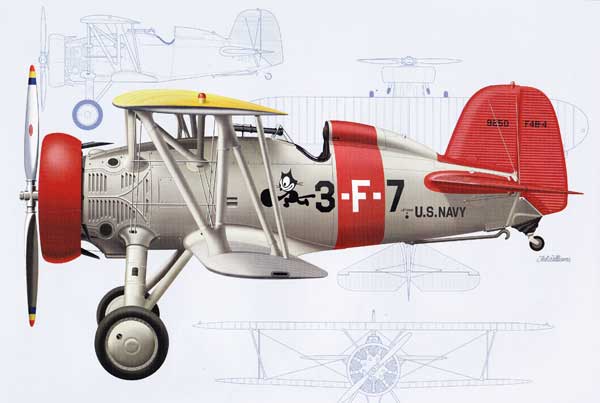

The F4B-3 served on the USS Saratoga before being reassigned to the

Marine Corps. Besides the semimonocoque fuselage, it featured a turtledeck

fairing aft of the cockpit. Twenty-one were built in all. The P-IZE most closely followed the modifications made to the F4B-3.

Lastly, the F4B-4 ended the program. Sporting several modern innovations -like the all-metal fuselage, stronger wings, and a redesigned tail for increased stability-theF4B-4 became the flagship of the program. With ninety-two built, not only was the F4B-4 the most-produced variant in the program, it also came to embody the quality design and innovative spirit of 1930s pursuit aircraft design.

Overall, Boeing produced 187 F4Bs for the Navy. Along with the P-12s made for the Army, 586 aircraft were produced before the program ended: the last F4B left the production line on the last day of February 1933.

The F4B and the P-12 had an amazingly long service life. F4Bs were still serving on American naval carriers as late as 1938, and in 1941, al the start of World War II, existing F4Bs and P-12s were used as radio-controlled drones. Boeing even exported aircraft based on this design to other nations-an uncommon practice at the time, since European-designed aircraft typically had the developmental edge.

The F4B and P-12 evolved from fabric covering and wooden wings to an all-metal semimonocoque construction. Boeing used smart marketing to analyze its buyers' needs, competently developing both a Navy and an Army version from the same basic airframe. It was only a matter of time before those same forward-looking engineers would overcome the inherent flaws built into every biplane design and perfect the monoplane. Soon, newer aircraft, like the Boeing P-26 Peashooter and other monoplanes, would take over the frontline duties, replacing the F4B andP-12 workhorses of the thirties. Sooner still, the warbirds of World War II would take to the skies to test the principles first put into practice by pioneering fighter aircraft like the F4B and P-12.

Boeing P-12 (F4B)

The Boeing P-12 was the definitive American fighter plane

of the 1930s, the golden age of aviation. Its chunky profile,

from the big, flat, reliable air-cooled radial engine to the

broad tail surfaces, set the pattern for American pursuit

planes until well into World War II. The P-12 became stockier as it developed, sturdy rather than fast and easy rather

than tricky to fly. It was a commercial success but not a

milestone of aerodynamic design. Although P-12s were

often decorated with the flashy stripes and colorful heraldry

of the peacetime military, the airplane was anything but

flamboyant.

The P-12 was the frontline pursuit plane of both the U.S. Navy and the Army Air Corps through the early 1930s. The prototype, designed to meet a Navy requirement, was developed from a series of Navy carrier fighters that dated back to 1925. The Army monitored the Navy's tests of the new F'4B, liked it, and immediately ordered ten equivalent P-12s. These were far more maneuverable than the Curtiss pursuits then in service. Some civil versions of the plane (Model 100) were developed into potent racers and stunt planes by such notable pilots as Milo Burcham and Howard Hughes.

A total of 586 of the P-12/F4B/Model 100 series were built from l928 to 1933, a remarkable production run during the Depression. The P-12 made the Boeing Company America's foremost fighter-plane supplier at a time when many companies were struggling to stay in business.

The main P-12 innovation was the use of bolted aluminum tubing in its fuselage structure in place of welded steel tubing. Beginning with Model E, this frame was covered entirely with sheet aluminum, making it stronger but lighter than earlier steel-and-fabric designs. As a result the P-12 could withstand higher G-loads in aerial maneuvers, and offered better engine vibration damping and improved protection for the pilot from gunfire or crashes.

Later models featured an engine cowling ring, a streamlined removable cover that greatly smoothed airflow over the bulky radial engines. (The Museum of Flight P-12 is one of the very rare earlier models without the cowling.) The series was developed through no fewer than ten models.

The P-12 was surprisingly influential - chiefly because of its sheer conventionality-and both the Soviet Union and Japan built derivatives. A Chinese P-12 was the first fighter to shoot down a Japanese aircraft in the Sino- Japanese conflict, downing two of its attackers before itself being destroyed by the third. Army P-12s had been replaced by P-26 monoplanes in frontline service by 1935, but the Navy's F4Bs soldiered on until 1938 because of their excel- lent maneuverability, low landing approach speeds, and resistance to the heavy wear of carrier operations. Both types were still in second-line service after Pearl Harbor.

The first Army P-12, the Pan American, was flown to Central America on a speed-flight goodwill mission by Capt. Ira C. Eaker in 1929. Nearly ten years later, Eaker completed the first transcontinental instrument flight in a P-12, flying all the way under a specially designed blind-flying hood. Eaker later became Commanding General of the U.S. Army Air Force Eighth Air Force in England.

Most of the surviving P-12/F4B airplanes were assigned to the Navy in 1941 for use as target drones. The handful of present-day survivors were either assigned as ground crew training aids or used by civilian air-show performers.

The Museum of Flight's P-12 is the second of eight single-seat civil Boeing Model 100s built along with the military ones (plus an additional 1004 two-seater). The first Model 100, which flew October 8, 1929, was bought by what is now the Federal Aviation Administration. The second, the Museum of Flight's aircraft, serial number 1143, was sold that year to the aero-engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney as an engine test bed. It was equipped with a quick-change engine mount and is reported to have flown with three different P&W engines in one day to demonstrate its versatility. The third was retained by Boeing as a test aircraft and later sold to the movie stunt pilot Paul Mantz, who at one time owned both it and the Museum of Flight aircraft. The fourth 100 was sold to Japan. Two more 100s, designated Model 100E, were exported to Thailand, where one survives in the Thai Air Force Museum, in Bangkok, and the eighth was another engine test bed for Pratt & Whitney.

|

A spiffy Howard Hughes, circa 1930, with his extensively modified supercharged racing Boeing 100A. It reportedly could do 225mph. |

The one and only two-seat 100A was modified for racing by the young Howard Hughes. Hughes, it seems, was not taken seriously as an airman until he won a sportsman pilot's air race over Miami in the 100A in 1930. Later on, decked out with rakish streamlined wheel spats, a deeper cowl, and a taller fin, the Hughes plane had a 30-year career as an air-show performer, being flown by Col. Art Goebel and a succession of others until 1957, when it was destroyed. After its career with Pratt & Whitney, the Museum of Flight's aircraft was sold to Milo Burcham on September 27, 1933. He modified it for skywriting and air-show work, painted it blood red, added fuel and oil systems for inverted flight, and flew it upside down from Los Angeles to San Diego. In 1936 he won the World Aerobatic Championship at the Los Angeles National Air Races in it, beating specially designed European stunt planes and their government- supported pilots.

Number 1143 was also a movie star. It appeared in Men with Wings in 1938 and in an early 1940s movie, title unknown, in which it was disguised as a British Gloster Gladiator fighter. It may have been damaged at that time. Mantz bought it for spare parts in 1948 (ten years after Burcham had sold it) and reassembled it to look like a two-seat Curtiss F8C-2 Helldiver for the film Task Force. (Mantz, by the way, became known as "Mr. Upside Down" by flying inverted in the third Model 100, the next one off the Boeing line, in a wheel-to-wheel air-show stunt with Frank Clarke.)

The Museum of Flight's airplane has been restored as an early P-12, a representation made easy by the fact that the sole difference between the military P-12 and the Model 100 was the lack of armament on the civil version. The Model 100's reduced weight made it faster than the military P-12/F4B, nudging some of the 100s close to the 200-mph range.

This aircraft was discovered as a basket case in Florida by Seattle attorney Robert S. Mucklestone, who bought it in early 1977 in partnership with Boeing chief of test flight S. L. "Lew" Wallick (Pictured Below). Orville Tosch headed the restoration team. The machine guns that would have armed a P-12 have been simulated on the Museum's aircraft, and it bears the "Kicking Mule" insignia of the famed 95th Pursuit Squadron, based during the early 1930s at March Field, near Riverside, California.

|

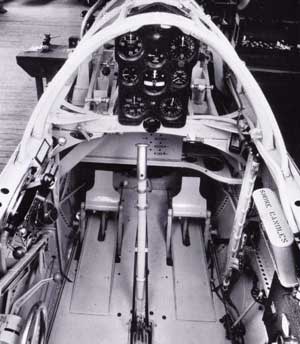

Cockpit of the Boeing F4B. |

|

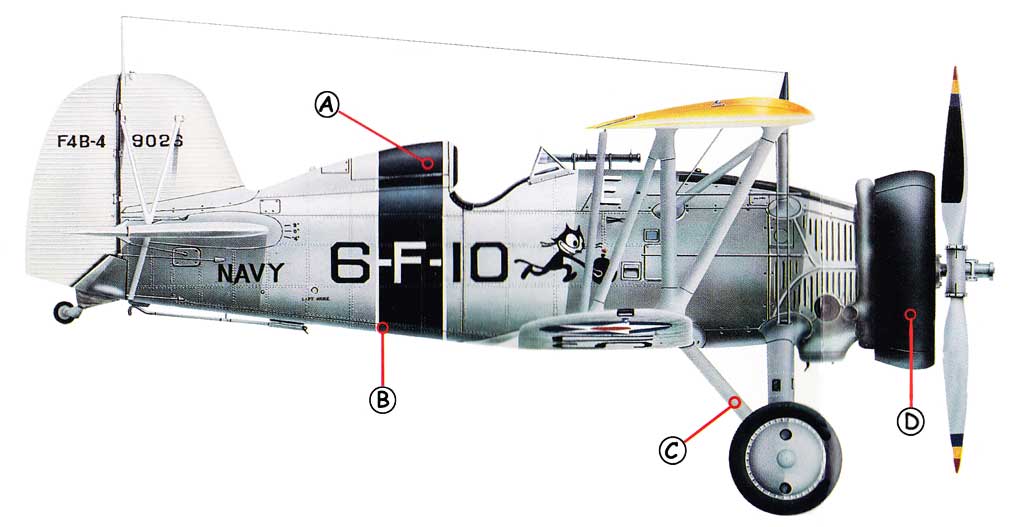

The "Felix the Cat" insignia was the squadron badge of fighter squadron VF-6, operating from the USS Saratoga in 1935. |

Specifications

Length: 20 ft 4 in |

|

|||

| A: A compartment in the headrest housed a dinghy in case the pilot was forced to crash-land in the sea. This version also was radio-equipped. | B: The fuselage frame of all F4Bs was built of welded tube steel for strength. Stressed metal skins replaced fabric on the fuselage of the later versions, but all F4Bs retained a fabric- covered wing. | C: The undercarriage of the F4B needed to be strong. Even with the low speeds of biplane fighters, landings on carrier decks were often very hard. | D: The nine-cylinder Pratt & Whitney Wasp radial was the forerunner of a family of engines that would power U.S. Navy fighters throughout World War II. |