Bowlus-Baby-Albatross - $$8.50

The Bowlus BA-100 Baby Albatross glider was designed by sailplane designer Hawley Bowlus in the mid-1930s. Designed to be a more affordable and easier to assemble glider than his previous designs, the Baby Albatross was sold fully constructed by the factory or in pre-fabricated kits.

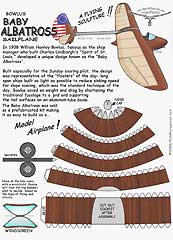

Bowlus Baby BA-100 Albatross Sailplane

The BA-100 Baby Albatross is the most familiar and numerous of a series of "pod-and-boom" designs by Hawley Bowlus, and the first of his designs to be built on a production line. Design of this glider began as early as1936, and the components for these gliders were fabricated at Bowlus' factory between the years of 1938 and 1942. They were sold as kits ($385) or as complete gliders ($750). Though the exact numbers are in dispute, approximately 75-90 kits were sold, and 50-60 Baby Albatrosses were actually built and flown a remarkable completion rate for any kit-built design. Some of these specimens are painted; others display the beautiful mahogany woodwork of the pod under a clear coat of varnish. (Soaring, May 1955)

Thanks to you and Kancho for the latest download. Was very

taken by

Thanks to you and Kancho for the latest download. Was very

taken by

the beautiful lines and finish of this glider and thanks

for the

interesting history that accompanied this release.

When one evaluates the progression of American

wooden gliders intended for amateur assembly ( and outright

construction) these are some of the more significant milestone

aircraft.

1956 Stan Hall Cherokee II

1956 Briegleb BG-12

1966 Miller Tern

In each case, it is interesting to see how the designer

wrestled with

cost/complexity/performance.

our timing could not be better. Jeff Byard's BA-100 Bowlus

Won Grand Champion at the IVSM last week- and just today

was returned to its hangar in Tehachapi. Cam

..The Baby Bowlus!! I have been waiting for that ever since seeing it at Udvar Hazy. Now I just need to figure out how to cover the wings with clear stuff, like the one the Smithsonian has! Keep 'em coming! John Freeman

Thanks to you and Kancho for the latest download. Was very taken by the beautiful lines and finish of this glider and thanks for the interesting history that accompanied this release.

Nice work on the Bowlus Baby Albatross!Have posted the news of the new model on the Rec Aviation Soaring (RAS)

Newsgroup. (Posted Blue Mouse to the same place last week). I got responses from the UK, so people do read it... Cam

Bowlus BA-100 Baby Albatross

Hawley

Bowlus, born in 1896 in Illinois, built and flew a glider modeled

on a Wright

Brothers type in 1912. He moved to the west coast. His interest

in gliding was revived by the news from Germany and in October

1929 he became the second American citizen to achieve the 'C'

soaring badge, flying a 14.3 meter span sailplane of his own design

and construction. He followed this with a US record duration of

one hour, twenty minutes.

Hawley

Bowlus, born in 1896 in Illinois, built and flew a glider modeled

on a Wright

Brothers type in 1912. He moved to the west coast. His interest

in gliding was revived by the news from Germany and in October

1929 he became the second American citizen to achieve the 'C'

soaring badge, flying a 14.3 meter span sailplane of his own design

and construction. He followed this with a US record duration of

one hour, twenty minutes.

In 1930 he visited Elmira for the first US National Soaring Contest and met Gus Haller, Wolf Hirth and Martin Schempp who were at this time associated in the Haller Hirth Sailplane Manufacturing Company. With Hirth, in 1931 Bowlus started a training school using auto towed launches, a method invented in the USA. It enabled training flights, and soon thermal soaring, to be done from flat ground.

The training school closed when Hirth went back to Germany, taking these new ideas with him. Bowlus returned to California where he designed and built, with the aid of students from the Curtiss Wright Technical Institute, the Bowlus Super Sailplane. This was strongly influenced by the Wien, with similar airfoil sections and general arrangement, single spar wing with plywood skinning, but Bowlus was not content to make a slavish copy. The wing, in two pieces, had a rectangular center section with the tips tapering, but with a slightly curved outline to the ailerons to come closer to the ideal elliptical form. On this prototype there was no dihedral.

To have a wheel on a glider was unusual in Europe but when cars were used to move the new generation of large and heavier gliders about on the ground, wheels were almost a necessity. Wheeled dollies and carts were used, but these had to be removed before flying and replaced after landing. (The idea of a 'drop off' dolly came later.) In the USA, towing gliders with airplane was becoming quite common, while in Germany still this was regarded with distrust. It had been done as early as March 1927 by Gerhard Fieseler and Gottlob Espenlaub as a stunt in air shows. For the glider to take off behind an airplane or tow car, a proper undercarriage was a sensible development. The earliest American 'primary' and 'secondary' sailplanes usually had wheels.

Bowlus

was the first designer to fit a wheel on a high performance sailplane.

Instead of V struts there was a single strut which, at the lower

end, was attached to the wheel bearing plates rather than to separate

fittings on the main fuselage cross frame. The struts were much

wider in chord than usual, with a streamlined cross section built

up like a small wing with fabric covering. Like the Musterle,

which Bowlus had seen at Elmira, the cockpit was fully enclosed

and faired with a plywood canopy, except for portholes at the

sides.

Bowlus

was the first designer to fit a wheel on a high performance sailplane.

Instead of V struts there was a single strut which, at the lower

end, was attached to the wheel bearing plates rather than to separate

fittings on the main fuselage cross frame. The struts were much

wider in chord than usual, with a streamlined cross section built

up like a small wing with fabric covering. Like the Musterle,

which Bowlus had seen at Elmira, the cockpit was fully enclosed

and faired with a plywood canopy, except for portholes at the

sides.

Warren Eaton, a founder member of the Soaring Society of America, ordered a sailplane from Bowlus and the Albatross 1, christened Falcon, was built, with slightly more span and this time with a ,gull' wing. The structure was strengthened. Bowlus fitted split trailing edge flaps under the inner wing as a landing aid. The plywood skinning was not birch as in Europe but mahogany which, when varnished, gave the Falcon a dark, reddish color and a luxurious appearance. Richard Dupont ordered the Albatross 2, which was completed without the flaps and skinned with spruce ply. In his new aircraft Dupont took off from Harris Hill, Elmira, on 25th June 1934, soared in thermals eastwards until within sight of New York city. He landed after 247 kilometers, a world distance record although technically disallowed because it did not exceed the previous figure by the requisite 5%. Later Dupont set the US height record at 1897 meters and became the second American to gain the Silver C badge, No. 32 on the international list (after Jack O'Meara, No 12). In 1935 he won the American Championship again in the Albatross, which was then sold to Chester Decker who became Champion with it the following year.

Both these sailplanes survive, Falcon in the Smithsonian collection and Albatross 11 at Harris Hill in the National Soaring Museum. Bowlus built more of the Albatross type but how many actually were completed is not certain. Efforts to restore at least one have been made.

William Hawley Bowlus designed and built the BA-100 Baby Albatross.

It was a step back in performance from the handful of Bowlus-Du

Pont Senior Albatross sailplanes (see NASM collection) that Bowlus

designed and built during the mid-1930s. However, each Senior

Albatross was a handcrafted masterpiece that cost $2,500.00 and

few depression-era pilots could afford them. A Baby could be had

for less than one-third that price and Hawley Bowlus must have

realized that he could make more money, and better serve the soaring

community, with a simpler and less costly sailplane. He abandoned

the quest for all-out performance to concentrate

on making motorless flight more accessible to the masses and the

Baby Albatross was the result.

William Hawley Bowlus designed and built the BA-100 Baby Albatross.

It was a step back in performance from the handful of Bowlus-Du

Pont Senior Albatross sailplanes (see NASM collection) that Bowlus

designed and built during the mid-1930s. However, each Senior

Albatross was a handcrafted masterpiece that cost $2,500.00 and

few depression-era pilots could afford them. A Baby could be had

for less than one-third that price and Hawley Bowlus must have

realized that he could make more money, and better serve the soaring

community, with a simpler and less costly sailplane. He abandoned

the quest for all-out performance to concentrate

on making motorless flight more accessible to the masses and the

Baby Albatross was the result.

Precisely how the name Baby Albatross originated

remains lost in time but the following explanation seems probable.

'Albatross' undoubtedly referred to the large, soaring seabird

that frequents the California coast and many other shores. The

bird can remain aloft for days at a stretch. The motto, 'On the

Wings of an Albatross,' adorned each Senior Albatross built by

the short-lived Bowlus-DuPont Sailplane Company. During the mid-1930s,

the Senior Albatross flew higher and farther than any other motorless

aircraft of American manufacturer. An astute businessman could

see that a 'Baby' version of the famed Senior Albatross had built-in

name recognition with the sailplane pilots.

'Baby' did not just imply a direct lineage to its older sibling. During design and construction of the first Baby Albatross, Ernest Langely and Jim Gough brought the unfinished wings for a Grunau Baby II to Hawley Bowlus and asked the master woodworker for help to finish them. In layout and dimensions, the BA-100 wings bear a striking resemblance to the wings of a Grunau Baby II. Bowlus did make the Baby Albatross ailerons larger and lighten the structure.

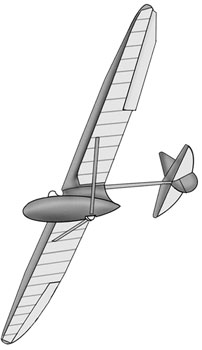

When he designed the BA-100 fuselage, Bowlus broke completely with tradition. He introduced a streamlined capsule around the cockpit and joined it to the empennage, using an aluminum tube, a feature that set it apart from any other glider of its day. The tube looks like much like irrigation pipe but on the first 65 Baby Albatross sailplanes, it was actually an extrusion manufactured by Alcoa from 17ST aluminum alloy. Beginning with serial number 66, Bowlus adopted a boom rolled from 2024-T3 aluminum sheet riveted at the seam by workers in the Douglas plant in Santa Monica, California.

The Baby Albatross was different in other ways, too. Hawley Bowlus offered to sell finished BA-100s at the factory and ready-to-fly, or as a series of affordably priced, mail-order kits. Each kit contained sufficient components, partially finished, to build a major component such as the rudder or wings. This option in particular appealed to many pilots who flew on very limited budgets during the 1930s. The Baby Albatross was a good, but not outstanding, performer, best described as a utility sailplane that could introduce pilots to the joys of soaring. It became, by far, the most successful aircraft that Bowlus developed. Kit production at the Bowlus factory was financially backed by some of the big names in aviation such as Jack Frye, president of Transcontinental & Western Airlines, Rubin Fleet at Consolidated Aircraft, engine builder Al Menasco, Glenn L. Martin, Jack Northrop, and Donald Douglas. The Baby Albatross might have sold in the thousands, had World War II not intervened.

The earliest known drawing of a Baby Albatross is

dated February 1936 so Bowlus had probably begun to think about

this design some time in 1935. Bowlus and Don S. Mitchell built

the first example in a lean-to adjoining Bowlus's backyard shop

in San Fernando, California. Many years later, Mitchell was to

design an interesting series of all-wing ultra lights. Bowlus

and Mitchell began building the first Baby early in February 1937

and the aircraft was finished one year later. The  Smithsonian's

National Air and Space Museum now owns this glider.

Smithsonian's

National Air and Space Museum now owns this glider.

Mitchell worked on the glider almost around-the-clock but for several months Bowlus could spare only nights and weekends. The demands of supporting his wife, Ruth, and their four children during the Depression frequently distracted him from building the first Baby.

Bowlus and Mitchell built three more prototypes before commencing kit production. The NASM Baby is the 'prototype of prototypes' and it differs from the other three in some important ways: Bowlus used cables for aileron control rather than heavier, but more precise, push-rods. He also skinned the ailerons with plywood but chose not to rig them to move differentially to minimize adverse yaw. Bowlus built the main spar using 'I-beam' construction while the wing nose ribs were constructed using truss-type techniques. The elevators are the same type fitted to the Senior Albatross and the landing wheel, with lift strut attachment fittings, is a two-piece casting. According to one account, this Baby Albatross is fitted with the aluminum nose cap from the Bowlus Senior Albatross number 3, registered G13780.

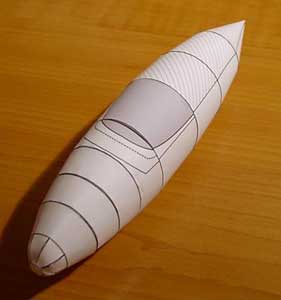

All four prototypes had forward fuselage pods built from sections of plywood that Bowlus and Mitchell 'scarf-jointed' together using glue, screws, and nails. A 'scarf-joint' refers to the shaping of the joined edges of two pieces of wood. The edges are sanded to a sharp angle so that they meet with no gaps and the maximum gluing surface possible. On a continuously curving shape such as the Baby Albatross pods, no two plywood edges met at the same angle so each edge had to be precisely, and laboriously, shaped by hand. The result is a series of conical sections that gradually taper into an attractive, streamlined shape.

Kit production actually began with the second prototype.

Although Hawley Bowlus built the wing ribs for this sailplane,

he sold them to Al Shatsel who assembled the airplane at the Bowlus

factory. Shatsel finished it on March 27, 1939, and flew the glider

until wartime restrictions on flying private aircraft near the

coast grounded the Baby Albatross late in 1941. Parts of this

aircraft survived into the late 1990s.

Kit production actually began with the second prototype.

Although Hawley Bowlus built the wing ribs for this sailplane,

he sold them to Al Shatsel who assembled the airplane at the Bowlus

factory. Shatsel finished it on March 27, 1939, and flew the glider

until wartime restrictions on flying private aircraft near the

coast grounded the Baby Albatross late in 1941. Parts of this

aircraft survived into the late 1990s.

None of the kits was equipped with a canopy or windshield. Bowlus left these details for the individual builder/pilot to decide, based on the type of flying he planned to do and the climate he preferred to fly in. The Baby was also not equipped with spoilers to improve glide path control but a number of owners did add them later. This was a significant omission in a glider aimed at the mass market; but the designer must have carefully weighed the tradeoffs. Without spoilers, the aircraft demanded greater piloting skill during landing but the wing construction was considerably easier to build and weighed less than a wing with the devices installed.

Fuselage pod construction changed dramatically between the prototypes and the kits. Bowlus abandoned the laborious and time-consuming 'scarf-jointed' pod and adopted the same techniques used to build the fuselage on Lockheed monoplanes such as the Vega. Wiley Post, Amelia Earhart, Roscoe Turner, Ruth Nichols, and other record-setters flew these remarkable aircraft from 1928 to 1935. They established some of the most important records in aviation history. The Vegas flown by Amelia Earhart and Wiley Post are preserved in the NASM collection. Fuselage skin molds made of concrete were key to the patented Lockheed process. Two female molds were used to 'lay-up' right and left halves of the skin. For the Baby Albatross, layers of 1/32-inch mahogany and poplar were laid into each mold with glue sandwiched between veneers. An inflatable bag was placed over the wet layers, and then a concrete male mold bolted securely atop the bag. Several inches of space remained between the female and male molds. The bag was inflated to evenly distribute about 10 pounds-per-square inch of pressure and the whole assembly set aside to dry. After removing the finished half, workmen trimmed and dressed it before gluing and nailing it to an internal framework. A molded pod also reduced the number of parts needed. It required only six frames versus eleven for the scarfed pod. The finished molded pod was strong, rigid, and streamlined.

A conventional, three-axis, control stick could

not be used in the narrow cockpit so Bowlus used a stick for pitch

control but mounted a smart-looking 'butterfly' wheel on top to

control roll. He used this same arrangement on the Senior Albatross.

The pilot pushed conventional rudder pedals to control yaw. A

simple panel usually held the basic instruments: altitude, airspeed,

and compass.

A conventional, three-axis, control stick could

not be used in the narrow cockpit so Bowlus used a stick for pitch

control but mounted a smart-looking 'butterfly' wheel on top to

control roll. He used this same arrangement on the Senior Albatross.

The pilot pushed conventional rudder pedals to control yaw. A

simple panel usually held the basic instruments: altitude, airspeed,

and compass.

The Baby Albatross performed well enough to qualify comfortably as an intermediate sailplane, circa 1938. It could fly at a maximum lift-to-drag ratio of 19:1 at an airspeed of 35 mph. Bowlus set the redline, or never-exceed speed, at 62 mph. A pilot's impressions of the Baby Albatross published in the late 1990s described handling as "both fun and challenging." He found roll and yaw easy to control but not pitch. "It is the pitch control that demands a great deal of respect. All BA-100s are very pitch sensitive due to the all-flying or "pendulum" elevator design. Some apparently more so than others."

These handling quirks did not deter pilots from

making a number of notable flights. Eastern Airlines Captain J.

Shelly Charles of Atlanta bought

the kit for Baby Albatross serial number 104 and finished it early

in 1939. He made a number of impressive flights in this aircraft

including a distance flight of 263 miles. During another flight,

he soared to an altitude of more than 10,000 ft.

On June 6, 1939, Woody Brown flew a Baby Albatross (serial number 8) named "Thunder Bird" a distance of 280 miles from Wichita Falls, Texas, to Wichita, Kansas. With this flight, Brown established the U. S. National sailplane record for distance flown to a declared goal. C. Wright Robertson of Durban, South Africa, bought the kit for serial number 112. He sold the finished sailplane to the Durban Gliding Club in November 1939 for 132 Pounds Sterling. This Baby Albatross continued to fly until it was destroyed in a crash in December 1955. According to Bowlus records, Florence "Pancho Barnes" Lowe, owner and operator of the Happy Bottom Riding Club saloon at Muroc, California, bought serial number 118. Kit units 1, 2, 3, and 4 were shipped to her by December 15, 1939, but no further information is known. After World War II, the club became a favorite test pilot hang-out.

The Baby Bowlus was not designed for all-out competitive flying but a number of owners ignored this fact. At least three Baby Albatross sailplanes disintegrated when they were flown into thunderstorms during soaring contests. Flown as the designer intended them, the Baby was a safe airplane that demanded an attentive pilot.

Bowlus continued to produce Baby Albatross kits on a regular basis before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 reduced the production rate to almost nothing. Factory records do not confirm it but Californian Steve Lowry owns a Baby Albatross with a factory-installed data plate stamped with serial number 190. This suggests that the Bowlus factory produced parts for at least 90 aircraft. This Baby Albatross was one of the several gliders finished after the war. Glider pilot and historian Jeff Byard has estimated that glider enthusiasts built and flew no more than 50 to 60 Baby Albatross sailplanes.

Today, only 17 Baby Albatross aircraft are known

to exist. There are large gaps in the histories of most of these

aircraft and the first Baby, now at NASM, is

no exception. Ironically, Bowlus flew the first Baby Albatross,

registered NX18979, very little but Don S. Mitchell clocked 273

hours flying it. He and the Baby were towed aloft by almost every

conceivable means: automobile, airplane (40-hp Piper Cub), pulley,

winch, and bungee-launch. Even a galloping horse hauled this glider

airborne on several occasions. Mitchell and competition pilot

Jack O'Meara took the sailplane to the 1938 U. S. National Glider

Contest held at Harris Hill in Elmira, New York, and Mitchell

made two flights off the Hill. Harris Hill is now home to the National Soaring Museum.

Today, only 17 Baby Albatross aircraft are known

to exist. There are large gaps in the histories of most of these

aircraft and the first Baby, now at NASM, is

no exception. Ironically, Bowlus flew the first Baby Albatross,

registered NX18979, very little but Don S. Mitchell clocked 273

hours flying it. He and the Baby were towed aloft by almost every

conceivable means: automobile, airplane (40-hp Piper Cub), pulley,

winch, and bungee-launch. Even a galloping horse hauled this glider

airborne on several occasions. Mitchell and competition pilot

Jack O'Meara took the sailplane to the 1938 U. S. National Glider

Contest held at Harris Hill in Elmira, New York, and Mitchell

made two flights off the Hill. Harris Hill is now home to the National Soaring Museum.

U. S. Navy Lt. Horace E. Tennes purchased it in August 1939. The following month, Ed W. Hudlow, Aeronautical Inspector, Civil Aeronautics Administration, issued an Airplane Tow Permit to Tennes to tow the sailplane behind a powered aircraft. During the spring of 1940, Tennes was assigned to Navy Fighter Squadron VF-6 based at Naval Air Station Coronado, California. Between March 8 and March 18, 1940, Bowlus Sailplanes Inc. carried out the following work on his glider: "Recover Baby Albatross 100, wings, struts, elevators. Install instrument in instrument board. Check ship thoroughly." This Baby had probably seen considerable air time since Bowlus and Mitchell had rolled it out two years earlier.

An Aircraft Airworthiness Authorization certificate was issued on July 8, 1941, to Lt. Tennes, now at Naval Air Station San Diego, California, for "experimental testing within the 6th CAA Region." Details about these experiments remain unknown. Tennes went on to command fighter squadron VF-86, nicknamed the Wild Hares, from June 1944 to January 12, 1945. That day, he assumed command of fighter-bomber squadron VBF-86, nicknamed the Vapor Trails, until the unit disestablished on November 21, 1945.

Exactly what befell the sailplane during the war years is not known but Tennes probably stored it, pending his return to civilian flying activities. In 1946, John R. Hed and Charles H. Whitmore of North Port Airfield near White Bear, Minnesota, bought the Baby Albatross. Hed and Whitmore enjoyed some great flying adventures in the aircraft, then sold it to B. A. Wiplinger of St. Paul, Minnesota, on December 16, 1954, according to the bill of sale. Wiplinger had his fun and then sold the airplane to Ralph P. Kliegle on November 3, 1958. Kliegle lived in Hampton Falls, New Hampshire. On April 11, 1963, Kleigle donated the airplane to the Smithsonian Institution.

The comments below are from the 'Sailplane

Directory' site:

The Baby Albatross, which flew in 1937, was a production

design for both kits and complete sailplanes. Bowlus produced

kits until the outbreak of World War II in 1942, and in 1944 Laister-Kauffman

bought the rights but produced no aircraft before going out of

business. The wing is reminiscent of the German Grunau Baby design,

and the pod is a molded plywood unit. No spoilers are provided,

but some have been modified by owners to provide them. Many other

modifications were carried out, including one Baby with a steel

tube pod built by Schweizer. Many soaring notables had a Baby

Bowlus as their first ship, including Dick Johnson, Dick Schreder

and Joe Lincoln, and flights of more than 250 miles have been

made. One example belongs to the National

Soaring Museum. The Vintage Sailplane Association has plans.

ATC.

The Soaring Connection

Legendary glider pilot and builder Wm. Hawley Bowlus built some

rather famous aircraft during his career.

Among these were:

The Spirit of St. Louis. Bowlus was the shop

foreman at Ryan Aircraft, in San Diego, California, and supervised

the 1927 construction of Charles Lindbergh's famous trans-Atlantic

airplane.

Bowlus' sailplane #16, built in San Diego, California

(1930), is commonly known as the Paper Wing on account of his

using kraft paper for his wing rib shear web.

Bowlus' S-1000 and Model A series of sailplanes,

also built in San Diego. Both of these two series resembled the

Paper Wing but had conventional "stick & gusset" ribs. Bowlus

broke the one hour duration record (eventually to more than 9

hours) flying a S-1000 along Pt. Loma, in San Diego. Bowlus' friends

Charles and Anne Lindbergh flew Model As.

The Bowlus-duPont "Senior Albatross" series of sailplanes. These were the first true sailplanes to be built in the US, and were built in San Fernando, California in 1933 & '34. Of this four glider series, three were built for Richard (Dick) duPont and one for SSA founder Warren Eaton. The Albatross I was used by duPont to win the US Nationals in 1934 and to set a World Distance Record in 1935. The Albatross II was used by duPont to set a World Distance Record in 1934, and Lewin Barringer used it to place 2nd in the 1934 US Nationals. I own the Albatross II, which is currently under restoration.

Bowlus' Baby Albatross sailplane, which was one of the first kit-built gliders offered to the soaring public. Approximately 100 kits were produced in San Fernando from 1936 to 1941. This pod & boom glider is often called "cute.

|

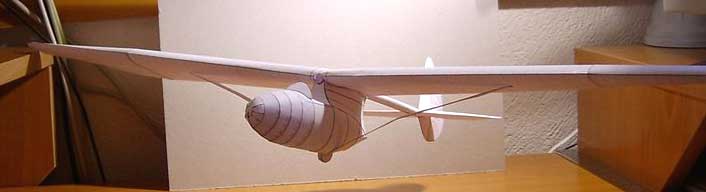

These are

examples of the Bowlus Baby Albatross sailplane black

and white version. A fw minor changes have been made since

this photo was taken at Kancho's Studio in Bulgaria. |

|

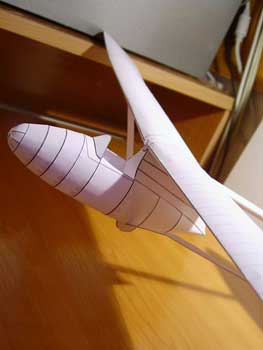

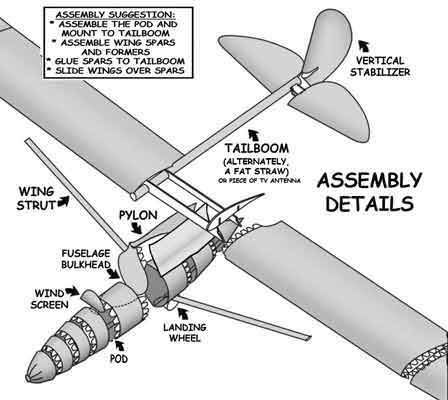

Beta build-notice

the massive wingspan-more photos below |

Tail boom is just rolled over a narrow diameter dowel and glue. Don't score the glue tab |

|

Specifications for the Bowlus BA-100 Baby Albatross

|

Span: 44.5 ft Wing Area: 150 sq.ft. Aspect ratio: 13.2 Airfoil Go 535 (mod) Empty weight: 300 lb. Payload: 205 lb. Gross weight: 505 lb. Wing loading: 3.3 lb./sq. ft. Structure 1-strut-braced wood/fabric wings; wood/fabric all-moving tail surfaces, metal tail boom; wood pod. |