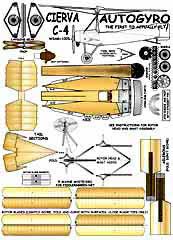

Autogyro-C4 - $$4.50

The failures of Cierva's previous designs, the C.2 and C.3, had led him to understand that he needed to overcome the problem of dissymmetry of lift in order to get an autogyro to fly without rolling over. He noted that the problems that he was experiencing with his full-size aircraft were not found in the models that he had successfully flown.

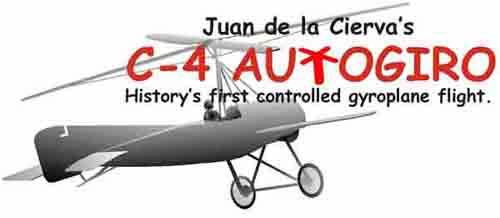

The 1923 Cierva C-4 Autogyro-First to fly!!!

There is some controversy about the first flight date of the C-4 but the most reliable evidence is that on January 17, 1923, in its latest form the C-4 made the first controlled gyroplane flight in history, a flight which has been described as the most significant since the first flight of the Wright brothers.

There is some controversy about the first flight date of the C-4 but the most reliable evidence is that on January 17, 1923, in its latest form the C-4 made the first controlled gyroplane flight in history, a flight which has been described as the most significant since the first flight of the Wright brothers.

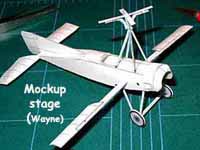

Wayne White, a serious Autogyro model designer and Geologist, has also designed the Weir W-2 Autogyro, and the Rotabuggy Flying Jeep...

The late Frank Courtney, who did much if not most of the test-flying in England for Cierva, once told me that the fixed wing appendages were largely there to reassure pilots, who didn't quite trust the barely visible disk over their heads.

We recently returned from a trip to Paris, where we visited the marvelous Musee de l'Air. Was delighted to see their two Cierva's, one winged, the other wingless. Keep up the great work, Cordially, Bill Hannan

During the war, 529 squadron (at Halton) of the RAF was equipped Cierva Autogiros, produced as the Avro Rota mark-1 for the very important and top secret job of helping to calibrate radar, a job that was done very early in the morning and practically every morning as it meant they could stay in place longer to check the calibration. None of the autogiros actually saw combat, though it is thought they would have been very difficult to shoot due to their slow speed and and maneuverability. Tim Harris (5/06)

Cierva C-4 Autogyro downloadable cardmodel

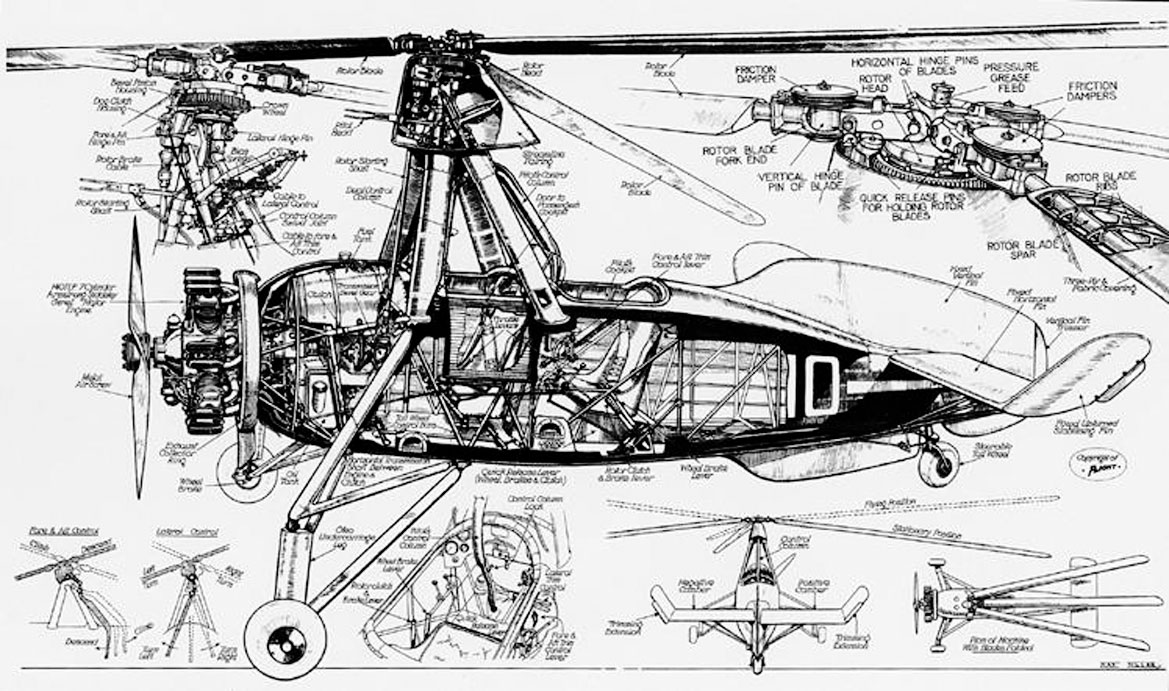

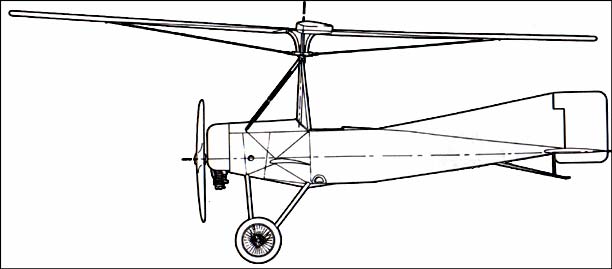

The new design, later identified as C-4, but known at the time as Autogiro No. 4, had a single four-blade rotor, 26 ft 3 in diameter. The rotor blades were of Eiffel 101 symmetrical section 28 in wide and were articulated at their roots and braced downwards with cables and upwards by rubber shock absorbers allowing them a vertical flapping motion. These restraints prevented the blades rising too high or dropping too low while at rest or when rotating at less than flying speed. The flapping hinges were below the plane of the blades with bent blade roots so that the blades flew flat rather than coned. Blade construction was of tubular steel spars, wooden ribs, and fabric covering. Normal speed of rotation was about 140 rpm. As in the C-3, the fuselage probably came from a Sommer monoplane; indeed, the fuselage, the Le Rh6ne 9C engine-even the tail surfaces and landing gear (in modified form)-may have been the very ones used in the C-3. The C-4 had only an elevator and no fixed stabilizer. Lateral control was to be provided by a sideways-tilting rotor hub.

The C-4 was completed in April/May 1922. Jose Maria Espinosa

Arias tested it at Getafe from June onward, for many months. It

crashed several times and was tried in fifteen different forms,

plus three or four lesser modifications. Changes included shortening

the fuselage, increasing the track of the landing gear, and substituting

a larger 32 feet diameter rotor with blades of Eiffel 106 section.

The last change was made after a hinge had failed on one of the

blades of the original rotor, fortunately without catastrophic

results.

The C-4 was completed in April/May 1922. Jose Maria Espinosa

Arias tested it at Getafe from June onward, for many months. It

crashed several times and was tried in fifteen different forms,

plus three or four lesser modifications. Changes included shortening

the fuselage, increasing the track of the landing gear, and substituting

a larger 32 feet diameter rotor with blades of Eiffel 106 section.

The last change was made after a hinge had failed on one of the

blades of the original rotor, fortunately without catastrophic

results.

The freely flapping blades were found to have overcome the problem of the unbalanced lift of the advancing and retreating blades. The rising advancing blade automatically reduced its incidence to the relative airflow, and hence its lift, while the retreating blade did the opposite. Because the centrifugal forces acting on the blades were about ten times the lift that they generated, the blades took up a mean coning angle of about one in ten with the plane of rotation. Articulation of the blades had also completely removed any gyroscopic effect from the rotor.

These tests established, however, that the pilot's lateral control by tilting the rotor head, as then designed, was too heavy to be practical. The pilot was unable to restrain violent oscillations of the control column transmitted from the rotor. Therefore, as the fifth modification of the CA, the rotor hub was fixed. At a later stage still, despite Cierva's reluctance to use airplane-type controls, ailerons on outriggers were added to provide control in roll. Actually, the C-4 was found to fly quite well in calm conditions without any lateral control at all, although the rotor head had to be permanently offset somewhat to prevent the aircraft from rolling over on the ground. Ailerons were needed in certain circumstances and these lateral control surfaces were to remain a feature of all Cierva's designs until 1932. Later they were incorporated into fixed wings. In its final configuration, the C-4 had a fixed, slightly offset rotor head and ailerons. It had its first tests in this form on January 10, 1923, when, encouragingly, it rolled over on the ground the opposite way to all previous accidents. It took a week to repair the damage.

There is some controversy about the first flight date of the C-4 but the most reliable evidence is that on January 17, 1923, in its latest form the C-4 made the first controlled gyroplane flight in history, a flight which has been described as the most significant since the first flight of the Wright brothers.

Piloted by Cavalry Lt Alejandro Gomez Spencer, a flying instructor at the Spanish Flying Corps flying school at Getafe and "a Spanish gentleman whose surname and appearance both indicate an English ancestry,' it made a steady straight flight of 600 ft at a height of about 13 ft across Getafe airfield. A further series of similar flights after engine trouble on January 20 were repeated before official military and Aero Club observers on January 22. The latter included General Francisco Echague Santoyo, director of Air Services, and Don Ricardo Ikuiz Ferry, president of the Spanish Royal Aero Club Commission. The C-4 was then transported to Cuatro Vientos military airfield and on January 31 was flown again by Spencer on an officially observed circular flight of 2.5 mi in 3.5 minutes at a height of more than 80 ft. The speed range of this aircraft in level flight was estimated at between 40 and 60 mph and the rate of descent, at low forward speed without power, at 6 to 10 ft/sec, although it was, in fact, almost certainly considerably higher than this.

The excellent low-speed characteristics of the Autogiro were effectively demonstrated on January 20 when the C-4 accidentally got into a steep nose-up attitude (nearly 45 degrees to the horizontal) after engine failure at a height of about 25-35 ft. The Autogiro's reaction to this situation was to descend vertically quite slowly, and to land undamaged without running more than 1m. most significant since the first flight of the Wright brothers. Piloted by Cavalry Lieutenant Alejandro Gomez Spencer, a flying instructor at the Spanish Flying Corps flying school at Getafe and a Spanish gentleman whose surname and appearance both indicate an English ancestry, it made a steady straight flight of 600 ft at a height of about 13 ft across Getafe airfield. A further series of similar flights after engine trouble on January 20 were repeated before official military and Aero Club observers on January 22.

The latter included General Francisco Echague Santoyo, director of Air Services, and Don Ricardo Ikuiz Ferry, president of the Spanish Royal Aero Club Commission. The C-4 was then transported to Cuatro Vientos military airfield and on January 31 was flown again by Spencer on an officially observed circular flight of 2.5 mi in 3.5 minutes at a height of more than 80 ft. The speed range of this aircraft in eye level flight was estimated at between 40 and 60 mph and the rate of descent, at low forward speed without power, at 6 to 10 ft/sec, although it was, in fact, almost certainly considerably higher than this.

The excellent low-speed characteristics of the Autogiro were effectively demonstrated on January 20 when the C-4 accidentally got into a steep nose-up altitude (nearly 45 degrees to the horizontal) after engine failure at a height of 25-35 ft. The Autogiro's reaction to this situation was to descend vertically quite slowly, and to land undamaged without running more than 3 f).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Video of C-4 maiden flight (2023)

"Some months ago, in April 2023, and to commemorate 100 years of first C-4 autogyro flight, a real C-4 replica flew again. An amazing moment."(Javier Fanlo García)