Curtiss Robin - $$4.95

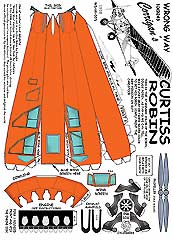

The Curtiss Robin, introduced in 1928, was a high wing monoplane with a 90 hp V8 OX-5 8-cylinder engine. It was later fitted with the more powerful Challenger engine, which developed between 170 and 185 hp. NOTE: Model B (90 hp Curtiss OX-5 engine), Model C-1 (185 hp Curtiss Challenger engine), and Model J-1 (165 hp Wright J-6 Whirlwind 5 engine) The J-1 version was flown by Douglas Corrigan (nicknamed "Wrongway") as well as The Flying Keys

The Story of Wrong Way Corrigan and his Curtiss Robin

"When I came down through the clouds I noticed I had been reading the compass needle backward."

"When I came down through the clouds I noticed I had been reading the compass needle backward."

No one believed Corrigan's explanation, especially the aviation authorities in both Ireland and America, who suspended the rebellious pilot's license and ordered his aircraft dismantled. Upon his return to America,"Wrong Way" Corrigan was greeted as a hero. More than a million people lined New York's Broadway for a ticker-tape parade honoring the man who had flown in the face of authority.

Pilot Douglas Corrigan sought permission from the Civil Aviation Authority to fly across the Atlantic from New York to Ireland, but he was turned down on the grounds that his plane was in poor condition. Corrigan seemed to accept the ruling, but when he took off from New York on July 17, 1938, he banked sharply to the east and headed out over the ocean. Twenty-eight hours and 13 minutes later, Corrigan landed in Ireland, innocently explaining that his 180-degree wrong turn must have been due to a faulty compass.

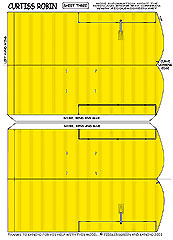

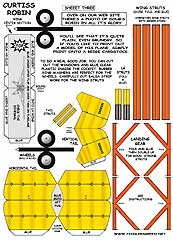

Robin that Wrong Way Corrigan flew to Dublin, Ireland is simply the B&W version printed on buff cardstock.. The Fiddlers Green MEGA AC

Mr. Corrigan became a recluse in the 1970's (when his son died in a private plane crash, I believe -- I have to check my references).However, he was lured out to celebrate the anniversary, and he seemed to enjoy his revived celebrity. His plane had been stored for decades in his garage, but it was taken out and reassembled.They even got the engine running again, but the FAA made sure Douglas was NOT going to fly again. Like Lindbergh, Corrigan had his gas tanks up front, moving his instruments and gauges to the passenger's compartment. His forward view was completely blocked by the makeshift gas tanks, so no wonder he got lost -- he literally couldn't see where he was going! ;-) The plane was taken back to his garage, and after Corrigan's death in 1995, it remains un displayed. Hopefully his heirs will donate it to a museum someday. David Okamura

I agree, Wrong Way Corrigan is hero of mine too. I have always believed that his miscalculation was a deliberate act to get round the authorities and bloody good luck to him. The only mystery is why he took such meager rations with him - makes methinks that he made his decision at the very last minute. Pitya chap caught short in a cockpit over an ocean - figs, for goodness sake! (notorious for making you "regular") Thanks for the new model. Excellent. Peter (0403)

Does Kancho even sleep? Nice job on this one too,...Enjoy the story of Corrigan at every telling. I worked with a Brit named Corrigan and he didn't seem to appreciate being called "Wrong Way," even after having been told the tale. His displeasure seemed to fan the flames, especially the Irish and Scots in thecrowd...Big thanks... Wayne (0403)

I haven't checked it out yet but this being April is it true that the Wrong Way kit has the instructions all messed up so you en dup with model of a double decker bus? Derek (4/03)

|

Clear Cabin Curtiss Robin submitted by Bob Martin. Thanks Bob! |

The Legend of Wrong way Corrigan

A touch of the absurd came to aviation in July 1938, when a young California pilot (who had worked as a welder on The Spirit of St. Louis), Douglas Corrigan, made one of the most sensational flights of the era. Having flown his nine year-old, $900 Curtiss Robin to New York, Corrigan fueled up and took off after announcing that he planned to return to Los Angeles. When next heard from, Corrigan and his old plane were in Dublin, Ireland, where he said, "My name's Corrigan. I left New York yesterday morning headed for California, but I got mixed up in the clouds and must have flown the wrong way."

And so was born the wry legend of"Wrong Way" Corrigan. It was a likely story, and Corrigan stuck to it to the delight of everyone. He had violated enough rules and regulations to have grounded him for life, but he had so captivated the public imagination that any legal procedure would have caused a furor. So his flying license was suspended for five days (which Corrigan spent aboard an ocean liner, returning to New York for a hero's welcome). After a brief tour with his obsolescent Robin (which had a Department of Commerce "X," for Experimental, license-and even that had been granted reluctantly to the old "flying jalopy"), after writing a book and taking a fling at the movies, Douglas Corrigan settled down to growing oranges in California. His flight, of course, added nothing to the progress of aviation except for a little laughter in a world growing grimmer by the day.

Corrigan was the last of the early glory-seeking fliers. He flew a single-engine 1929 Curtis-Robin he'd bought off a trash heap for $310. He'd rebuilt it and modified it for long-distance flight. Like Corrigan, it was a hold-over from earlier days.

By now, Lindbergh's flight was eleven years old. Others had also flown the Atlantic, but it was still not a trick you'd try in any regular factory-ready airplane. Corrigan flew non-stop from California to New York in 1938. He'd filed plans for a transatlantic flight and was denied by aviation authorities. The piece of junk he was flying had no business challenging the Atlantic. So he gave up and filed a plan for a non-stop return to California.

He took off at dawn. A few puzzled onlookers watched him do a 180-degree turn and vanish into a cloud bank. Twenty-eight hours later, he stepped out of his plane in Dublin, Ireland, saying, "Just got in from New York. Where am I?

The authorities suspended his license while Corrigan stuck to his story: He'd got turned around, and his compass had malfunctioned. He'd meant to fly to California. The only people who were fooled by that wanted to be fooled. After all, he was the perfect anti-hero -- the little guy in his home-made airplane.

By the time the ship carrying Corrigan and his crated plane got back to New York, the suspension had been lifted. The city gave him a bigger parade than it'd given Lindbergh.The next year saw the first commercial transatlantic airline. The year after that saw 4-engine bombers being ferried off to war in Europe. Corrigan became a test pilot.

When Corrigan was 81, his old Curtis-Robin came out of mothballs and went on display at an air show. Corrigan, who'd grown reclusive, was suddenly so enthusiastic they put a guard on the plane, lest he try to take off one more time.

Picture Courtesy of Virginia Aviation Museum

Designed for the civil market by the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company, the Robin was a slender airplane of modest performance. This three-seat monoplane flew in the spring of 1928 with a 90-hp Curtiss OX-5, the engine that had powered Curtiss JN-4 Jenny trainers in World War I. Robins offered flight characteristics as straightforward as their appealing lines. A distinctive feature (shared with Fairchild cabin monoplanes of the period) was side cockpit windows that ran almost to the floor.

The biplane dominated aviation until Charles Lindbergh's historic

1927 flight from New York to Paris showed the world that the era

of the monoplane was truly at hand. His Spirit of St. Louis-like

the Stinson SM, Bellanca Columbia, and Ford Tri-motor-all featured

a single high wing and fully enclosed cabin. The Robin, built

to the same formula, was conventional in structure with a welded

fuselage built of rugged steel tubing that was rectangular in

cross section. Except for the cowling, the plane was entirely

fabric-covered. Orange with black trim was a common factory color

scheme. More than 300 Robins were fitted with the surplus OX-5

and sold to the civil market at $4,000. Others were powered by

the 170-hp.

The biplane dominated aviation until Charles Lindbergh's historic

1927 flight from New York to Paris showed the world that the era

of the monoplane was truly at hand. His Spirit of St. Louis-like

the Stinson SM, Bellanca Columbia, and Ford Tri-motor-all featured

a single high wing and fully enclosed cabin. The Robin, built

to the same formula, was conventional in structure with a welded

fuselage built of rugged steel tubing that was rectangular in

cross section. Except for the cowling, the plane was entirely

fabric-covered. Orange with black trim was a common factory color

scheme. More than 300 Robins were fitted with the surplus OX-5

and sold to the civil market at $4,000. Others were powered by

the 170-hp.

Curtiss Challenger (a six-cylinder, twin-row radial engine that was less than satisfactory) and the excellent 165-hp Wright J-6-5 Whirlwind. These later versions, with the added expense of new engines, sold for almost twice the price of the lethargic OX-5 Robin. but offered substantially better performance.

Robin production took place in St. Louis, Missouri, in association with the Robertson Aircraft Corporation, a local fixed-base operation that ran the contract air mail route between St. Louis and Chicago (Major William B. Robertson had been one of Lindbergh's financial backers). Some 750 Robins were built by the Curtiss-Robertson Airplane Manufacturing Corporation before the Depression and competition from newer types called a halt to production late in 1930.

One of aviation's most delightful records was set in a Curtiss Robin by Douglas 'Wrong Way" Corrigan. He left New York for California in July 1938 and touched down in Ireland 28 hours later, claiming he accidentally read his compass backward. The plucky pilot-who had been denied official permission to fly the Atlantic-thus earned his nickname and delighted the world.

Aviation's exuberant adolescence was also marked by a penchant

for endurance records. In July 1929, Dale Jackson and Forest O'Brine set an impressive record in the Challenger-powered St. Louis Robin.

With the help of aerial refueling, they remained aloft 420 hours

and

Aviation's exuberant adolescence was also marked by a penchant

for endurance records. In July 1929, Dale Jackson and Forest O'Brine set an impressive record in the Challenger-powered St. Louis Robin.

With the help of aerial refueling, they remained aloft 420 hours

and

17 minutes. When their mark was bested by a Stinson monoplane

the following June, they took off again in the St. Louis Robin

on July 21, 1930, and set a new mark of 647 hours and 28 minutes.

The greatest record for sustained flight was set five years

later in a Whirlwind-powered Curtiss Robin J-1 Deluxe named Ole

Miss.

After two unsuccessful attempts in 1934, brothers Fred and Algene

Key took off from Meridian, Mississippi. on June 4, 1935, and

landed again 27 days later. There to greet the exhausted fliers

on the evening of July 1 were 35,000 wildly cheering spectators.

The Key brothers' total flight time was 653 hours and 34 minutes.

Among the dangers they had faced were severe thunderstorms and

an electrical fire.

During the flight, Fred and Al Key took turns manning the controls and sleeping on the extra fuel tank behind them in the cabin. They received food, fuel, and supplies 432 times through a sliding roof hatch from another Robin. A metal catwalk made in-flight maintenance and lubrication of the engine possible. Their Wright Whirlwind engine consumed 6.500 gallons of gasoline, at a rate of 10 gallons per hour, and 300 gallons of oil. Their estimated ground track was 52,320 miles, or more than twice the circumference of the earth.

Almost twenty years after its famous flight, Ole Miss was offered to the National Air Museum by the Key family. On July 2,1955, Fred Key flew the famous Robin, now fully restored, to National Airport in Washington, D.C., where it was formally presented to the Smithsonian Institution.

The Curtiss Robin was a modest high-wing cabin monoplane produced just before the Great Depression. Only 750 were built, but the Robin was popular with its pilots and was used for a number of World Record flights.

The Robin was of mixed construction with wooden wings and a

fuselage made of steel tubing, the whole

being fabric-covered. An OX-5 engine initially powered Robins,

but later models had more powerful Wright Whirlwind, which substantially

improved performance. First flown in 1928, Robins were manufactured

in St Louis, MO, before the Depression put a halt to production

in 1930.

In July 1929, Dale Jackson and Forest O' Brine set an endurance record of 420 hours, 17 minutes in the air,using in-flight refueling. Later, they set a new mark of 647 hours, 28 minutes using the same plane, named St Louis. Five years later, brothers Fred and Algene McKey took off from Meridian, MI to set the greatest record for sustained flight. Starting on June 4, 1935, they took turns at the controls and sleeping on an extra fuel tank in the rear cabin. Supplies were passed from another Robin through a hatch in the roof and a metal catwalk enabled the brothers to service the engine in-flight. Flying through all weathers and surviving an electrical fire, the exhausted brothers eventually landed on July 1, after 653 hours and 34 minutes in the air.

Another story-well worth reading..

Life wasn't easy for young Doug Corrigan. His father had left

the family and his mother ran rooming houses in Los Angeles until

her early death. After finishing ninth grade, Doug quit school

to earn money at small wages in a bottling plant, a lumber yard,

and in home construction. He was bitten by the flying bug, too,

and in 1925 paid $2.50 for his first airplane ride, in a Jenny.

Life wasn't easy for young Doug Corrigan. His father had left

the family and his mother ran rooming houses in Los Angeles until

her early death. After finishing ninth grade, Doug quit school

to earn money at small wages in a bottling plant, a lumber yard,

and in home construction. He was bitten by the flying bug, too,

and in 1925 paid $2.50 for his first airplane ride, in a Jenny.

After that, nothing could keep him out of the air. Later that year, he scraped together $5.00 for his first flying lesson at the age of eighteen. He soloed in March, 1926. Between other jobs, he spent his hours around the dusty Los Angeles area flying fields. His luck turned good for the moment and he got the job at San Diego with Ryan. He earned his transport pilot's license, although it didn't do him much good.

At one time he worked at the new airfield at Palm Springs, California, which was only a few acres of soft desert sand on land owned by the Indians. He and others dragged a smooth strip on the sand and soaked it, baking the crust hard under the intense sun. Thus they could take off and land without the wheels sinking into the earth.

As a barnstormer, Corrigan reached the East Coast at Virginia Beach, Virginia. He and his partner obtained use of a field eighty feet wide and six hundred feet long, from which to carry passengers. At one end was a cornfield. In order to have enough takeoff room, the flyers paid the farmer to cut the tops off the corn.

However, the corn kept growing. Later, in his book That's My Story, Corrigan remembered, "We were picking cornstalks off the landing gear and tail surfaces after every flight." Once the right wing caught in the cornstalks. "We pulled the plane out of the cornfield and pulled about three bushels of corn off the wings and kept on flying."

The future hero learned about dying the hard way.

Late in 1931 he was on the East Coast and wanted to return to California. Despite the Depression, he had accumulated a little money. For $325 he bought a second-hand Curtiss Robin monoplane. That battered craft was to carry him to international renown later, but only after years of penny-pinching and wandering.

Doug and his brother Harry started west in the newly acquired plane, carving everything they owned. They used a roadmap as a guide, stopping in fields to earn a few dollars carrying passengers. They slept in the plane or on the ground. Several times they had to patch the Robin's fabric cover; once they bought gasoline from the tank of a farmers tractor to keep going. After eighteen days they reached California, having kept the plane at a regular airport only two nights.

All this time, Doug clung to his hope of flying the Atlantic,

Lindbergh style. As the Depression years of the Thirties moved

along, a few more Atlantic flights were made by well-prepared

expeditions, but regular passenger flights still were not practical.

All this time, Doug clung to his hope of flying the Atlantic,

Lindbergh style. As the Depression years of the Thirties moved

along, a few more Atlantic flights were made by well-prepared

expeditions, but regular passenger flights still were not practical.

Corrigan fell in love with that plane of his. He fussed over it the way young men today pamper their automobiles. Every spare dime he had went into improving it. There never was much money because he frequently was out of a job and broke. The Curtiss Robin had been built to carry four persons on rather short flights. Doug decided to remodel it as a single-seater and install extra fuel tanks where the seats had been.

Being a welder, he built and installed the tanks himself. He made a deal to buy a secondhand Wright J6-S engine and installed it in place of the Robin's original one. The engine, built in 1929 like the plane itself, developed 16S horsepower-not much by the rapidly improving standards of the mid-1930's but greater than the original.

Doing everything himself, Corrigan stripped the original fabric cover from the wing and fuselage, put on a new covering, and treated the body with preservative "dope." A friend who flew with him at that time told how they landed in a cow pasture and Corrigan insisted on sleeping with the plane that night. He knew that cows loved the taste of the fabric "dope" and feared they might eat the covering of the fuselage. He also installed new wheels.

As he kept remodeling the aging plane, Corrigan made cross country trips in it to check his long-distance navigation. Nothing seemed to matter much to him except that plane. His friends jokingly called it the "Corrigan Clipper."

During the 1930's airplanes became larger, faster, sleeker, and more powerful. Corrigan's Robin looked more and more out-of date, a fragile leftover from the pioneering days of the 1920's. It was smaller than Lindbergh's Spirit of St. Louis and carried less fuel. Federal regulations on planes and pilots grew much more stringent, too. The happy-go-lucky days of barnstorming were dying. Flying any place you wished, in any old "crate" you could coax into the air, was frowned upon. Aviation was becoming a business, not a gathering place for free souls like Douglas Corrigan.

He applied to the federal government in 1937 for a permit to fly from New York to London but was turned down. The inspectors needed only one look at "Corrigan's Clipper" to know that flying it over the Atlantic was a form of suicide they didn't intend to endorse.

Doug was out of a job again but worked through the winter of 1937 and spring of 1938 as an aircraft welder in Southern California. He was thirty-one years old. At night and on weekends, he flew his cherished plane on test flights. Grudgingly, a federal inspector granted him an experimental license for a nonstop flight from Los Angeles to New York, with the understanding that he could make the return nonstop trip westbound if everything went right.

Without fuss, and telling only a few friends he was going, Corrigan took off from Long Beach, California, on July 8, 1938, for New York with 952 gallons of gasoline. He figured he got about eleven miles to the gallon. so with luck and a tailwind he might make the trip nonstop. Experiments had shown that the plane got the best results by puttering along at eighty-five miles an hour, rather than being pushed at top speed of a little above a hundred.

The weather was rough and he needed twenty-seven hours to do it, but Corrigan landed the Robin at Roosevelt Field on Long Island after crossing the United States nonstop. Whenever he became sleepy, he stuck his head out the window and let the wind rouse him. Precisely four gallons of gasoline were left in the tanks when he landed. Although transcontinental nonstop flights still were far from common, hardly anyone noticed his feat. That suited him just fine.

One of those Corrigan did talk to during the next few days around Roosevelt Field was a prominent woman pilot, Ruth Nichols. He told her he was going to make a nonstop flight back to California via a southern route. Noticing that he didn't have a parachute, she offered to lend him one. He said no thanks because there wasn't room for one, and anyway the plane was all he had and if it fell to pieces he would go with it.

Indeed, Corrigan had practically nothing, not even a change of clothes with him. His plane had only the simplest instruments to guide it, and a map of the United States aboard showing his planned route back to the West Coast- south down the Atlantic seaboard and then westward across the southern United States to Los Angeles. During several cloudy days, Corrigan hung around the airfields and watched the weather reports. While waiting, he patched the weak spots in the plane's fabric.

On Saturday the sixteenth the weather was good all across

the United States, and he told people he would leave early the

next morning. He flew the Robin a short hop over to Floyd Bennett

Field and taxied it to a commercial hangar. There he gave the

engine a grease job and had the gasoline tanks filled' 320 gallons,

paying $62.26 in cash for the fuel.

Corrigan

wanted to take off just after midnight because, he said, he hoped

to have moonlight that night for his flight over the American

desert. Looking at the badly overloaded, battered plane, the airport

manager refused permission for departure until dawn. He ordered

flares ignited along the runway as an additional safety factor

and had a fire engine standing by.

Corrigan

wanted to take off just after midnight because, he said, he hoped

to have moonlight that night for his flight over the American

desert. Looking at the badly overloaded, battered plane, the airport

manager refused permission for departure until dawn. He ordered

flares ignited along the runway as an additional safety factor

and had a fire engine standing by.

At dawn Sunday, Corrigan turned over the propeller himself, checked the engine for loose parts, and climbed into the plane. Because the knob was broken, he tied the door shut with bailing wire. For food, he had a box of fig cookies and candy bars. With a wave to the handful of persons around the hangar, he made a long, laborious takeoff, rising barely fifteen feet off the ground at the edge of the field. "Corrigan's Clipper" groaned under the load; it had never before carried such weight and wasn't built for it.

Doug had taken off toward the east. The spectators watched for him to bank and head south and west for California. But he didn't. Instead, the plane was seen angling to the northeast.

"That's all right. He'll make the turn after he has gone a few miles and gained some altitude," one of the watchers said.

Corrigan's version of what happened after that sounds like an Irish fairy tale. In fact, it was just that, an elfin yarn spun with a straight face. It went like this:

As he

gained altitude and prepared to turn west, he said that one of

the two compasses in the cabin was not working because the liquid

had leaked out, a mishap he hadn't noticed earlier when he checked

the plane in the dark. However, since the second compass on the

floor had been set to fly a westerly course he turned the plane

until the parallel lines matched. By then, he was into fog: he

climbed above it and flew on, following the compass needle.

As he

gained altitude and prepared to turn west, he said that one of

the two compasses in the cabin was not working because the liquid

had leaked out, a mishap he hadn't noticed earlier when he checked

the plane in the dark. However, since the second compass on the

floor had been set to fly a westerly course he turned the plane

until the parallel lines matched. By then, he was into fog: he

climbed above it and flew on, following the compass needle.

About two hours later, he saw a city through a gap in the fog which he assumed was Baltimore, Maryland. Later he figured out that it must have been Boston, Massachusetts.

Still flying above the fog ten hours later, along what he assumed was a westward course, he felt his feet getting cold. No wonder they were chilly! they were soaked with gasoline leaking from the main tank. This didn't worry him much, because he assumed he could always land if the leak grew worse during the night, the leakage did increase. Pointing his flashlight down, he saw gasoline an inch deep on the cabin floor. He punched a hole in the floor with a screwdriver and let the gasoline drain out into the air below, carefully picking a spot for the hole so the inflammable dripping wouldn't hit the red-hot exhaust pipe.

Corrigan had planned to fly slowly to save gasoline, but the leak; caused him to speed up, on the theory that the faster he flew, the sooner he would reach California and the less time there would be for gasoline to drip out.

The American newspapers were puzzled in their Monday morning editions. Corrigan's plane had not been seen since it took off nearly twenty-four hours earlier. What had become of him~ They published headlines like "Mystery Flight" and "Vanishes Eastward."

After

flying all night, Corrigan came down through the clouds and was,

he claimed, puzzled to see water below him instead of land.

Since he had been flying "only" twenty-six hours without

a stop, he figured that he shouldn't be over the Pacific Ocean

yet. At this point, so he said, he discovered what he had done

wrong. He realized that he had been following the wrong end of

the magnetic compass needle the entire flight, and it had pointed

him over the Atlantic Ocean instead of toward California!

After

flying all night, Corrigan came down through the clouds and was,

he claimed, puzzled to see water below him instead of land.

Since he had been flying "only" twenty-six hours without

a stop, he figured that he shouldn't be over the Pacific Ocean

yet. At this point, so he said, he discovered what he had done

wrong. He realized that he had been following the wrong end of

the magnetic compass needle the entire flight, and it had pointed

him over the Atlantic Ocean instead of toward California!

He had just eaten some fig cookies when he noticed land below the plane. Crossing the green coastal hills, where there were no towns, he flew inland for about fort`77-five minutes until he reached ocean again. This, he decided, must be Ireland. And it was!

Flying south, Corrigan found a large airport with the name Baldonnell marked on it. He knew this was Dublin so he landed, after being in the air for twenty-eight hours and thirteen minutes.An army officer walked up to the plane, and Corrigan said to him, "My name's Corrigan. I got mixed up in the clouds and must have flown the wrong way"

That was his story.

When word flashed back to the United States about his remarkable

flight. He immediately became known as "Wrong-Way" Corrigan.

Nobody believed his tale, and aviation experts were astounded

that he had crossed the ocean in such a "crate," but

the world cheered his audacity and flying skill. He was a hero

who didn't look or act like one, a blithe individualist who had

thumbed his nose at the authorities and at the laws of probability

and gotten away with it. Not only had he flown the Atlantic without

an American permit, but he had lacked permission to land at Dublin.

For once, however, government officials had a sense of humor.

When word flashed back to the United States about his remarkable

flight. He immediately became known as "Wrong-Way" Corrigan.

Nobody believed his tale, and aviation experts were astounded

that he had crossed the ocean in such a "crate," but

the world cheered his audacity and flying skill. He was a hero

who didn't look or act like one, a blithe individualist who had

thumbed his nose at the authorities and at the laws of probability

and gotten away with it. Not only had he flown the Atlantic without

an American permit, but he had lacked permission to land at Dublin.

For once, however, government officials had a sense of humor.

As Corrigan boarded an ocean liner in Ireland, for the trip home, he was handed a cablegram from the United States Department of Commerce announcing his punishment for breaking the law. His pilot's license was suspended until August 4. That was the day the ship was due in New York. In other words, no punishment at all.

Back in the United States, Doug received the celebrity treatment-a ticker-tape parade in New York City, a meeting with President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House, and a nationwide tour in the faithful old Robin. Wherever he went, his hosts gave him joke gifts. The Liars Club of Burlington, Wisconsin, elected him a member. Many cities presented him with compasses. At Tulsa, Oklahoma, an Indian tribe initiated him as Chief Wrong Way, and Abilene, Texas, gave him a watch that ran backward.

Douglas Corrigan was the poor man's hero, shy and modest. Never once in public did he budge from his story.

|

Cockpit of the Curtiss Robin. |

Specifications

Crew: three Length: 25 ft 1 in Wingspan: 41 ft Height: 8 ft Wing area: 223 ft² Empty weight: 1,635 lb Loaded weight: 959 lb Max takeoff weight: 2,569 lb Powerplant: 1× Curtiss OX-5 liquid-cooled V-8, 90 hp Performance Maximum speed: 120 mph Range: 500 mi Service ceiling: 12,500 ft Rate of climb: 640 ft/min at sea level |

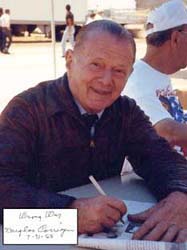

Here's

a picture of Douglas Corrigan signing autographs at the Long

Beach Airport Days on July 31, 1988.

Here's

a picture of Douglas Corrigan signing autographs at the Long

Beach Airport Days on July 31, 1988.