Hiller Hornet

The Hiller Hornet was an ultra light helicopter built in the 1950s by Hiller Aircraft, it was a unique design, as it was powered by two Hiller 8RJ2B ramjet engines that were mounted on the rotor blade tips. Versions were built for the United States Army and the United States Navy. Above: Hiller Hornet on display at the Hiller Aviation Museum in San Carlos, California.

Originally intended for the civil market with a price as little as $5,000, the Hiller Hornet was a tiny helicopter powered by ramjet engines mounted on the rotor tips. It was tested in 1956 as the HOE-1 or H-32 for the US Army for use as an artillery spotter or forward observation platform. For this role the Hornet lacked what we now call 'stealth', as it could usually be heard by the enemy and the glowing engines could be seen from a long distance. Hiller once claimed 'the Hornet's sound range compares favorably with that of a conventional-powered helicopter' but without an intercom system the pilots had to scream at each other to communicate. The museum owning the only remaining flyable example of the 17 Hornets built received complaints from neighbors a mile and a half away when they last flew it.

The high drag of the ramjets meant the blade angle had to be set to a very negative angle when power was cut, and this led to the Hornet plummeting at 49fps during auto rotation. Only a very skilled pilot could arrest this descent just before the ground.

The idea of using tip-jets to power a helicopter originated in World War II with an engineer named Friedrich von Doblhoff who worked in the design bureau of the German-controlled Wiener Neustadt Flugzeugwerke, a small factory in Vienna, which built light aircraft. Two prototypes were built at the request of thc German Navy and flown successfully, although flight experience showed that the fuel consumption of the tip-jets was prohibitively high.

Hiller Hornet

Stanley Hiller Jr. was one of those pioneers of vertical flight

who foresaw a helicopter in every garage. Instead of walking, pedestrians would fly their own minicopters. When a

February 1951 Popular Mechanics cover illustration showed

a suburbanite backing a bright yellow helicopter into his

garage while his neighbor flew overhead in a red one, the

flying machines looked surprisingly like the Hiller Hornet,

which had been announced that same year.

Stanley Hiller Jr. was one of those pioneers of vertical flight

who foresaw a helicopter in every garage. Instead of walking, pedestrians would fly their own minicopters. When a

February 1951 Popular Mechanics cover illustration showed

a suburbanite backing a bright yellow helicopter into his

garage while his neighbor flew overhead in a red one, the

flying machines looked surprisingly like the Hiller Hornet,

which had been announced that same year.

The late 1940s and early 1950s were a fertile period for the exploration of Vertical Takeoff and Landing (VTOL) concepts of all kinds. Turboprop fighters that sat on their tails and took off like rockets, "convertiplanes" that hovered like helicopters and used conventional propellers for horizontal flight, and various tilt-wing and tilt-rotor aircraft in which the rotors worked both as propellers and as lift devices were being built and tested. Stanley Hiller, designer of the YH-32 Hornet, an experimental helicopter powered by rotor-tip ramjets, was one of the most prolific innovators of that era.

Hiller became interested in helicopters in 1941, at the age of sixteen, after seeing pictures and films of Igor Sikorsky's first helicopter flights. When he decided to build his own helicopters, his first goal was to eliminate the tail rotor, which he felt robbed the lifting rotors of too much power that could otherwise contribute to direct lift. This may sound precocious for a sixteen-year-old, but Stanley Hiller was no ordinary teenager.

Six years before, he had constructed a toy automobile that he reportedly drove through the streets of Berkeley. At twelve he developed the Hiller Comet, a 19-inch model racing car that, according to a contemporary account, could do 107 miles per hour, guided by a cable around a circular course. Backed by his shipping-executive father and namesake, he formed Hiller Industries, which mass produced these sophisticated models with aluminum bodies formed by a technique young Hiller invented for die-casting nonferrous metals. This technique was used during World War II to manufacture aircraft parts such as window frames for the C-47, the military version of the DC-3. The Navy requested a draft deferment for Hiller, to enable him to continue his experimental work.

|

Hiller Hornet on the cover of Feb 1951 issue of Popular Mechanics. |

He formed the Hiller Aircraft Corporation in 1942 and developed the XH-44 Hiller-Copter, a double rotor craft that was his first attempt to solve the basic problem of helicopters: the torque, or twisting force generated by the engine, that makes helicopters want to spin in the direction opposite that of the whirling rotors. Hiller patented his system of coaxial double rotors that turn on a common shaft in opposite directions, canceling out each other's torque. In its public appearances, the machine's rotor drive and control mechanism was covered by canvas gloves to keep its design secret. Six men designed and built the Hiller-Copter, including Hiller and Harold Sigler, who engineered and sketched out the teenager's ideas, making design contributions of his own.

Aside from being the first workable coaxial helicopter, the XH-44 was the first helicopter to fly west of the Mississippi and the first to use rigid, all metal rotors, a feature unmatched by other manufacturers for more than a decade.

Yet another first: The XH-44 was the first truly stable helicopter so stable that Hiller often demonstrated it with both of his hands extended from the cockpit during flight. His work attracted financial support from the shipbuilder Henry J. Kaiser, who made Hiller's small group the Hiller-Copter Division of the Kaiser Cargo Company. The business arrangement ended in 1945 when Kaiser embarked upon his ill-fated "Henry J" car making venture. That year, Hiller formed United Helicopters Inc., to continue his work toward developing a simplified, easy-to-fly, low-cost rotary wing aircraft.

"Hiller is mature beyond his years," wrote the author of a Flying magazine profile of the nineteen year old inventor entrepreneur that appeared six months after the first untethered flight of the XH-44 at the University of California Stadium, Berkeley, on May 74,1944. "He exhibits no signs of self-consciousness as he sits in his paneled office, responds to inter-communication system calls, or handles a Washington long distance call.

"He is six feet tall, thin, and energetic. He speaks with reserve until the subject of flying is brought up. Then he becomes enthusiastic. . . ."

In 1946 he crashed in his latest XH-44 model. He then showed his flexibility by adopting the more conventional tail- rotor approach to controlling torque. The result was a milestone of helicopter design, the three seat Hiller 360. It first flew under the company designation UH-72 (UH for United Helicopters) and was certified by the Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) in 1948. Over the next two years, Hiller sold more helicopters for commercial use than all other manufacturers combined: a total of eighty two.

During the early fifties the 360 achieved a measure of fame in Vietnam, where a French Army captain, Valerie Andre, won the Croix de Guerre for flying solo medical evacuation missions-the first routine airlifts of wounded soldiers in history. Already an experienced parachutist and fixed wing pilot, Andre joined the French army straight out of medical school, served a year in what was then French Indochina, was trained to fly helicopters, and returned to the war in 1950. Flying many of her sorties under fire, she eventually rescued 165 wounded soldiers.

War in Korea increased Hiller's work force from 100 to 700, and the company eventually delivered more than 2,000 of the 360/UH-12 series over a production life of twenty years. Models included the Navy's HTE-1 and -2, the Army H-23 (later named Raven), and hundreds more sold to the air arms of a dozen countries. The 360/UH-12 series was intensively developed over its long life: the first thousand hours between overhauls helicopter was the Army's H-23D of 1957. The 12E, introduced in 1958, was a much-improved development of the 360 and was widely regarded as the finest piston engine helicopter ever built. Many were still in service as Army trainers during the mid seventies.

(The Museum of Flight also exhibits a perfectly restored example of the Hiller 12E, one of the two crop dusting helicopters with which Oregon based Evergreen International Aviation was founded in 1960.)

Hiller's adoption of the most widely accepted powertrain formula for helicopters didn't stop him and his engineers from continuing to explore a variety of approaches to the VTOL problem. Hiller Helicopters, as he had renamed his company to avoid confusion with the helicopter division of United Aircraft, was working during the early fifties on the Flying Platform, a ducted-fan aircraft controlled by the pilot's body inclination. Another approach was the Navy-Marine Corps XROE-I Rotorcycle of 1957, a one-man helicopter which could be collapsed into a parachute-droppable package and then quickly assembled with quick-release pins. Seven were built for the Navy and five more for commercial use. Late in the decade, the Hiller company was also at work on a tilt-wing "propelloplane," the X-18, whose wings (and the engines mounted on them) tilted up for takeoff or landing and rotated to horizontal for conventional flight. This project led to a transport-size VTOL prototype aircraft, the four-engine XC-142A, a joint venture among Ling-Temco-Vought, Hiller, and the Ryan Air- craft Corporation.

In 1951, Hiller unveiled another remarkable design,

the rotor-tip ramjet-powered HJ-1 Hornet. This could have

been the simplified, cheap, easy-to-fly helicopter he had

been aiming for ali along. At 7 feet tall, with a 23-foot rotor, it

would fit in some garages, and at the announced price of less than $5,000 it was competitive at the time with a sports car.

Hiller fully intended the Hornet to be the Volkswagen of

helicopters.

In 1951, Hiller unveiled another remarkable design,

the rotor-tip ramjet-powered HJ-1 Hornet. This could have

been the simplified, cheap, easy-to-fly helicopter he had

been aiming for ali along. At 7 feet tall, with a 23-foot rotor, it

would fit in some garages, and at the announced price of less than $5,000 it was competitive at the time with a sports car.

Hiller fully intended the Hornet to be the Volkswagen of

helicopters.

Those plans were shelved with the outbreak of hostilities in Korea. Nevertheless, a test batch of twelve of a slightly larger (7ft 8in) prototype with a tail rotor, the YH-32, was ordered by the Army in 1952 and delivered in 1956. A single Navy prototype was built but not accepted. The Museum of Flight's military YH-32 Hornet was found in a garage and in bad enough shape for the finder to wonder what it was. It was bought by Stanley Hiller, who had it restored and donated it to the Museum.

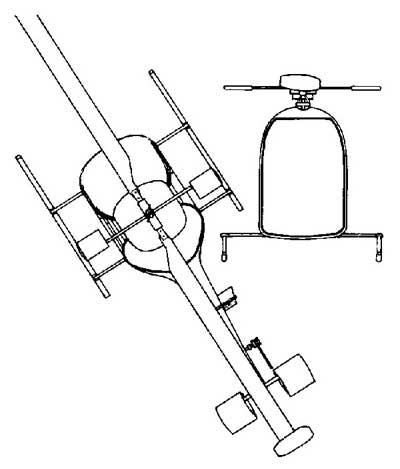

The Hiller company's idea was to eliminate most of the normal helicopter's weight by using rotor-tip powerplants "to eliminate antitorque requirements, complex engine installations, and large power transmission systems," as project engineer Harvey Holm explained at a helicopter design seminar in Los Angeles in 1953.

As Stanley Hiller explained to his biographer, former Museum of Flight curator Jay Spenser, the YH-32 Hornet was a proof of concept vehicle, intended to demonstrate the feasibility of rotor-tip power for an eventual giant "flying crane." Building the dozen Army test craft and using them in field conditions would prove the soundness of the rotor-tip power concept. In the giant flying crane, powertrain weight savings would translate directly into increased payload. The U.S. armed forces were eager to have such machines, and the concept appeared sound. Howard Hughes, no stranger to outsized aircraft concepts, built a flying test bed, the XH-17, with a main rotor diameter of 130ft, powered by compressed air carried along the rotors to tip nozzles from two platform mounted jet engines. It flew in 1952, and had it gone into production, it would have been the first helicopter to carry its own weight in useful load: a maximum loaded weight of 105,000 pounds. The ramjets Hiller was developing for the YH-32 would have been more efficient at the high speeds reached by the tips of such long rotors.

For these rotor-tip powerplants Hiller developed the first ramjet engines ever certified by the CAA in fact, the first American designed and built jet engines of any kind to be so endorsed. Ramjets have no moving parts and, because of their simplicity, can be very small. They are fed with air by their forward motion through it. A flameholder at the front with a fuel nozzle and ignition line ignites the fuel-air mixture. A combustion chamber from which the hot exhaust gases emerge completes the engine.

At very high speeds ramjets become efficient, and since rotor-tip speeds can approach the speed of sound, these small engines seemed better than anything then avail- able for such use. Hiller had been working to develop the ramjet through the late 1940s and had solved the problems involved in making engine parts from a heat-resistant but hard to form nickel alloy, Inconel X. The company had evolved a ramjet that was the size of a medium sized watermelon, weighed 12.71bs, developed 40lbs static thrust apiece (or 45 equivalent horsepower), and could be removed in minutes with a screwdriver, "even though," as Holm wrote, "the fuel flow rates then quoted for subsonic ramjets were little short of shocking."

The result was a paragon of simplicity and functional design. During two years of company testing it was discovered that the more or less conventional rudder used on the flying test stand (Hiller Model XIIJ-1) offered less positive yaw control than a small tail rotor, especially in crosswinds and at low rotor speeds during landing. The question of using tail rotors was decided by the military requirement for controlled lateral movement, so the military Hornets were designed with them after all.

It took five minutes to accelerate the rotors to 50 rpm by means of a small gasoline engine, since the ramjet cannot develop thrust while standing still. This might have proven troublesome in a battlefield environment but presumably would have allowed a morning commuter time for one last cup of coffee.

The fuel system, Holm explained to his professional colleagues in the summer of 1953, got tricky where the fuel had to be transferred to the whirling rotor blades on its way to the thirsty ramjets. A rotary seal at the bottom of the rotor installation and a "splitter tee" at the rotor head got the fuel on its way out along the blades, where centrifugal force took over. Unfortunately, this meant the fuel pressure varied according to rpm, from the 25-40 pounds per square inch developed by the fuel pump to as much as 2,500psi at maximum speed. This made quick acceleration or deceleration impossible because of the amount of fuel in the lines at any given time and the high pressures the system built up. And pilots like nothing more than immediate response when they operate the throttle.

Considering how advanced the power concept for the Hiller Hornet was, it seems almost unbelievable that the simple fiberglass tail boom was the most troublesome aspect of the manufacturing program. But fiberglass as a structural material was new in the early fifties. After trying various shapes, different chemical impregnation methods, and lay-up molding processes, by 1953 Hiller felt they had the problem licked. In the end, the Hiller Hornet concept was limited by two obvious factors. First, the problem of "shocking" fuel use in ramjets worked against the idea of a lightweight helicopter. As it was, the military test Hornets carried fifty gallons of fuel, good for twenty minutes aloft they would have needed to carry huge fuel tanks to have any kind of useful range. Second, of course, they were colossally noisy.

Though the Hiller company became what it was because of the Model 360 and Korean War production, it was that same war that wrote finis to Hiller's dream of a helicopter for everyman. Not every infantryman proved a good pilot. Good pilots thought the flying machines would become "backyard death-traps in the hands of amateur aviators." Not to mention the air traffic control nightmare.

These delightfully cartoony, egg-shaped helicopters turned out to be no more than a sidelight in America's assumption of leadership in helicopter technology after World War II. The powerplant and power transmission problems with helicopters have never been solved, but they have been substantially mitigated by the development of turbo shaft engines that offer power to weight ratios three times better than those of the piston engines that powered the first Sikorsky models. Since the Hiller Hornet appeared, powerplant technology has basically overshadowed the drawbacks of the conventional helicopter.

|

|

Rotor-tip-mounted ramjet propulsion was a promising alternative power system for rotorcraft, eliminating the transmission units of conventional helicopters. |

Here's the business end of the rotor-tip ramjet, you can see where the fuel line comes in and the sparking mechanism, fairly simple design. |

|

The first turbojet engine to be mounted on the tip of a helicopter rotorblade. This Williams Research Corporation unit turned up to 1,000 Gs. |

These images were taken by Chip at the Hiller Aviation Museum in San Carlos, California |

|

Here is a YouTube clip of the Hiller Hornet in action.

Specifications

|

Crew: two pilots

|

|

|||

| A: The no-torque ramjet system eliminated the need for a conventional tail rotor, making the Hornet very mechanically simple. | B: The Hornet was unveiled by Hiller in February 1951 and at that time the company was offering it for sale at a unit price of $5000. | C: The advantage of a rotor-tip propulsion is that there is no torque, which is created in conventional helicopters by the rotor's motion working in opposition to that of the engine. | D: The Hornet was able to run on a wide variety of fuels, but the fuel tank held only enough for 25 minutes flying or a range of 40 miles. |