Howard-Ike-Mike - $$5.95

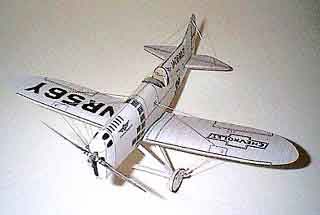

Both Howard MIKE and IKE are in this folder. The successes of Pete, the DGA-3 convinced Benny Howard that there was money in racing aircraft. Benny and his partner, Gordon Israel, started work on two new aircraft, the DGA-4s-a pair of look-alikes named Mike and Ike, both low wing, wire-braced monoplanes.

Benny Howard's MIKE and IKE

IKE, MIKE, and other race planes of the thirties are a breed apart from military airplanes. The men who built and flew them are also in a class by themselves, and although that brilliant era in aviation history is gone, we still can enjoy some of its glow through modeling the famous airplanes of the air races. Instructions available as free download (see below)

For years we've been getting mail and (recently) lots of email asking if we'll ever have a 1930's Racing Plane series.

We never really took them seriously until we got into this series. Historically, we see the racers as the spring-board to a great leap aviation made during WWII. Look closely at these designs and you'll see the seeds of the Zero, FW-190, and the P-47 Thunderbolt, just to name a few.

IKE, MIKE, and other race planes of the Thirties are a breed apart from military airplanes. The men who built and flew them are also in a class by themselves, and although that brilliant era in aviation history is gone, we still can enjoy some of its glow through modeling the famous airplanes of the air races.

Benny Howard's Darn Good Airplanes (DGA)

by Major Truman C. Weaver,

USAF (ret)

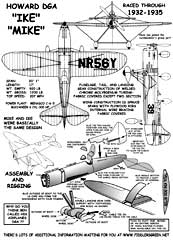

AFTER COUNTING THE trophies and money won by "Pete"

in the 1930 and 1931 races, Benny Howard decided that there was

money in the race game. He was also aware that "Pete"

was on the way to being outclassed and if he was to remain in

the winner's circle, he would have to do something about it. So

early in 1932 work began on two larger racers. The end result

was "Mike" and "Ike," (they look alike). The

two racers were almost identical, the only difference being in

the landing gears. They were both painted snowy white with shiny

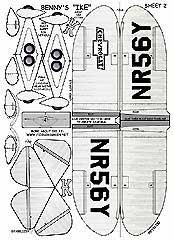

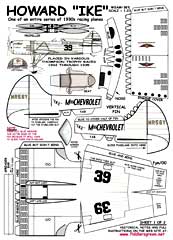

black lettering. "Mike" (DGA-4) drew license number

NR-55Y and race number 38, (race number 7 was used, at Omaha)'

while "Ike" (DGA-5), carried NR-56Y and race number

39.

AFTER COUNTING THE trophies and money won by "Pete"

in the 1930 and 1931 races, Benny Howard decided that there was

money in the race game. He was also aware that "Pete"

was on the way to being outclassed and if he was to remain in

the winner's circle, he would have to do something about it. So

early in 1932 work began on two larger racers. The end result

was "Mike" and "Ike," (they look alike). The

two racers were almost identical, the only difference being in

the landing gears. They were both painted snowy white with shiny

black lettering. "Mike" (DGA-4) drew license number

NR-55Y and race number 38, (race number 7 was used, at Omaha)'

while "Ike" (DGA-5), carried NR-56Y and race number

39.

Both racers were

low-wing, wire braced monoplanes, and like "Pete" were

very small and had a minimum of frontal area. There was a slight

difference in weight, "Ike" being a bit lighter of the

two. Both were powered by Menasco Buccaneer engines of 485 cu.

in. displacement, differing in octane ratings only. The engine

in "Ike" was set for a higher octane, thus giving a

little boost in horsepower. The extra horsepower and being a little

lighter may have accounted for "Ike" being the faster

of the two in 1932. Oddly enough, it was always a toss-up as to

which of the ships would be the fastest from year to year.

Both racers were

low-wing, wire braced monoplanes, and like "Pete" were

very small and had a minimum of frontal area. There was a slight

difference in weight, "Ike" being a bit lighter of the

two. Both were powered by Menasco Buccaneer engines of 485 cu.

in. displacement, differing in octane ratings only. The engine

in "Ike" was set for a higher octane, thus giving a

little boost in horsepower. The extra horsepower and being a little

lighter may have accounted for "Ike" being the faster

of the two in 1932. Oddly enough, it was always a toss-up as to

which of the ships would be the fastest from year to year.

Wing span of both ships was 20 ft. 1 in. and the fuselage was

17 ft. Long. The cockpit in each case was hinged on the side and

closed after the pilot was inside. A large hole for the pilot's

head was left open. Ventilation was assured by 30 small holes

drilled in the windshield. The cockpits were small and the pilot's

seat was level with the rudders. A slight difference appeared

in the engine cowling, with "Mike" having less cooling

louvers than "Ike" but a larger rectangular opening

on the left side of the cowl for cooling. "Mike" had

a cowl designed for a spinner, which was never used.

The landing gears on the two ships were very different. The gear on "Mike" was similar to that used on Pete. with the rather large wheels housing an internal shock; absorbing system needed to meet CAA (then ATC' requirements (both aircraft were built to these specification-but never certified because of cancellation of ATC races . "Ike" had a novel tandem gear arrangement consisting of two small wheels spaced about 20 in. apart and covered by a single wheel fairing, one on each leg. Howard stated that this was done for a gag, but the gear did prove rather successful. However, ground handling and spotting the aircraft in the hangar presented problems since the wheels did not caster. Single wheels with spats replaced the original gears on both ships.

Ben Howard entered "Ike" in six events at the 1932 National Air Races. He flew three of them himself -taking two firsts and one second. During one of the races he was pressed closely by Roy Liggett in the Cessna CR-2 with Johnny Livingston and his short-winged Monocoupe a length behind. Bill Ong ran fourth in this event but later got "Mike" wound up and took second under same conditions.

Two major air races occurred at the same time in 1933, so Howard sent Harold Neumann to the American Air Races with "Ike". The tandem wheels had been removed and replaced with normal small panted wheels. This resulted in a weight saving and improved streamlining so a performance improvement resulted. Harold participated in only one event, placing third. He was dogged by engine trouble during the balance of the meet, so he stepped into the Folkerts SK-1 to finish the races.

Roy Minor and "Mike" were sent out to take over the Nationals. "Mike" had been modified considerably. The spinner design for the cowl had been abandoned and the large rectangular opening on the side was closed. Many of the cowl louvers were also faired in. A set of small wheels and wheel pants replaced the large un spatted wheels of 1932.

Minor and "Mike" really took over the National Air Races of 1933, copping four firsts, two seconds, two two fifths, two thirds and one fourth. Both ships were present at the 1934 Nationals, with no apparent changes other than a recovering job on Mike," whose lettering was now in gold edged with black. Roy Hunt was in the cockpit of "Mike" and Harold Neumann in "Ike". Hunt picked up two fifths and Neumann finished with two fourths. Best closed course speed for "Ike" this year was 211.55 mph, 30 mph faster than "Mike".

Jokingly called the 1935 "Benny Howard National Air Races", this was a banner year for Ben. His racers won the Bendix, Thompson and Greve Trophy races that year.

"Ike" was sponsored by the Chevrolet Division of General Motors and was known as "Miss Chevrolet". It was equipped with a special carburetor and now held the worlds inverted speed record. However, the ship did not participate in the races as Neumann wiped the gear off during qualifying runs. Harold came back strong winning the Thompson in "Mr. Mulligan" and three firsts in the 550 cu. in. class with "Mike". Marion McKeen had worked the bugs out of his new Brown B-2 and gave Neumann some uninvited competition by finishing less than one mile per hour behind "Mike".

The 1936 Nationals certainly were not a repeat for Howard. "Mike" was the only one to finish a race that year. Harold Neumann ran a speed dash in it, clocking 223.714 mph, which placed him fourth in the Shell event. Joe Jacobson placed fifth in the Greve and nosed over on landing. The 1936 races were not profitable to Ben Howard.

Only "Ike" appeared at the 1937 Nationals, now traveling with the Fordon-Brown Air Shows. It did not race as the Menasco was not functioning properly. Both "Ike" and 'Mike" were brought by R. Rovner of Cleveland and were to participate in the 1939 races, but due to technical difficulties did not appear. The only visible change was a yellow paint job on each.

'Ike" and "Mike" are still in existence, located in Ohio where it is rumored that they are undergoing restoration. During the racing career of these two ships the honors for top speed changed hands many times. "Mike" turned a speed dash of 241.61 mph compared to 239.63 mph for "Ike," but closed course speed honors went to "Ike" with 215.2 mph, with 214.4 mph for "Mike". Not much difference in speed performance, yet they differed as much as 30 mph in single events in which both performed. Could it have been piloting?

|

Elation! Neumann accepts

the Greve trophy from Louis W. Greve for his sweep of the race

with times of 212.716 mph, 194.930 mph, and 207.292 mph. Elation! Neumann accepts

the Greve trophy from Louis W. Greve for his sweep of the race

with times of 212.716 mph, 194.930 mph, and 207.292 mph. |

HALLEY'S COMET WENT by in 1910 and Ben O. Howard whizzed past the spectators at the National air races, Chicago, in 1930. Both events were equally startling. In fact, I had expected Halley's Comet, but the comet-like Howard was a complete surprise to me. Neither before nor since has there been such a popular racing combination as Bennie and "Pete," the little white plane with the Gipsy engine, in which he won five first places and finished third in the Thompson trophy with a speed of 162.80 mph. Since then many pilots have flown faster, but none have created the sensation that Ben O. (just plain Oh) Howard created at Chicago in 1930. That was the high point of his life, everything since then has been a stepping down from that climactic period of his career-until he finally got married-and that was the end of him as a speed demon.

|

His ship won $6,925 prize money, next to the highest amount, won by the Wedell-Williams Air Service, $13,400. That must have cheered Ben a great deal and sweetened his outlook on racing, which rather soured on him last year. You see, Ben entered a period of prosperity with "Pete," which paid for itself four times over; and then, greatly elated, he built "Mike" and "Ike," only to learn that he had over judged his cash prize market. He was so annoyed about it that he went around at Cleveland in 1932 and bit pieces out of the grandstand and Cliff Henderson. There's one thing you can count on at National; air races: there's always a good snappy fight about something or other. It's only put on to add interest to the sport of racing and to keep us limber. When all else fails, Ray Brown shadow-boxes with Jack Berry, or Roscoe Turner misses a pylon and hits the contest committee. But it's all in a spirit of good clean fun.

Ben Howard was born in Palestine, Texas, Feb. 4, 1904, and despite his best efforts to avoid any education whatever, was held in school long enough to finish half a term in high school, when he leaped clear of all guidance and attached himself to a soda fountain. They paid him too much money, for one week he had $10 saved and bought a Standard for the ten, promising to pay another ten every week for fifteen weeks. Well, next day he sent word from the hospital that the former owner could have the wreckage of the craft. Ben had taken it up with enthusiasm, and nothing else. He spent a hot summer in a plaster cast, which is an uncomfortable way to spend a hot summer in Texas.

When the 17 year old flying enthusiast was able to hobble around again, it was that fine gentleman, the late R. W. Mackie, who gave him some needed flying lessons in return for mechanical work. This was in Houston in the winter of 1922, after which Ben flew a year for C. C. Cannon, an oil operator with drilling operations scattered all over south Texas. He paid for the Standard he had used up, went to Nicholas-Beazley in the summer of 1924 and then back to Houston to build his first ship, DGA-1. "Mike" and "Ike" are DGA-4 and DGA-5. I wonder if the Department of Commerce guesses what DGA stands for. The answer is Damned Good Airplane!

In the spring of 1926 Ben joined J. Don Alexander at Denver,

where he stayed two years, was fired twice, and went to Dearborn

to insert rivets in Fords for a month, then joined Robertson Air

Lines in St. Louis to fly J-5 Fords on the Chicago run. Next spring

he was fired by his dear friend, Bud Gurney, and went to work

for T. A. T., which was just starting. By Christmas he was fired

for reasons that seemed adequate to Dog Collins, even if they

didn't to Ben, so he went to work for Universal, flying mail back

and forth between St. Louis and Omaha in Pitcairns and Stearmans,

and mail and passengers from Chicago to Tulsa in F-10's, until

he told his boss, Bob Dentz, a few truths, and got fired in September,

1930.

In the spring of 1926 Ben joined J. Don Alexander at Denver,

where he stayed two years, was fired twice, and went to Dearborn

to insert rivets in Fords for a month, then joined Robertson Air

Lines in St. Louis to fly J-5 Fords on the Chicago run. Next spring

he was fired by his dear friend, Bud Gurney, and went to work

for T. A. T., which was just starting. By Christmas he was fired

for reasons that seemed adequate to Dog Collins, even if they

didn't to Ben, so he went to work for Universal, flying mail back

and forth between St. Louis and Omaha in Pitcairns and Stearmans,

and mail and passengers from Chicago to Tulsa in F-10's, until

he told his boss, Bob Dentz, a few truths, and got fired in September,

1930.

In November he was working for N. A. T., in time to be canned in December because they shut down the Stout Airlines. For a couple of months he rebuilt "Pete" and then went to work for Bill Bliss, in person, for Century Airlines, but was offered his job back with N. A. T., so returned to that company, where he has been ever since, flying between Kansas City and Chicago. He is careful not to get fired from N. A. T. because he is running out of airlines. Besides, he's married now and settled down. Probably the sensible thing to do will be to stay on the airline, and shuttle back and forth between Kansas City and Chicago until he finally wears out. We all wear out at something or other - usually something we don't care especially about. In Ben Howard's case he has an undoubted genius for designing racing planes - and I hope he designs a dozen more of that interesting series known as DGA.

Specifications for the Howard DGA-4&5

|

Length: 17 ft Wing Span: 20 ft 1 in Weight Empty: 920 lb Max Weight: 1200 lb Powerplant: Menasco C-6-5 Buccaneer 6-cylinder engine 300 hp Performance Maximum Speed 207 mph |