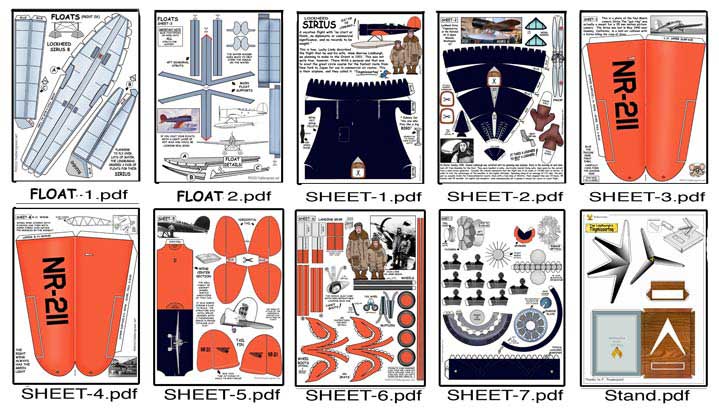

Lockheed Sirius - $$7.50

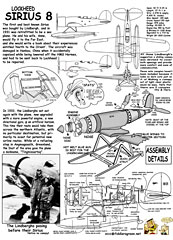

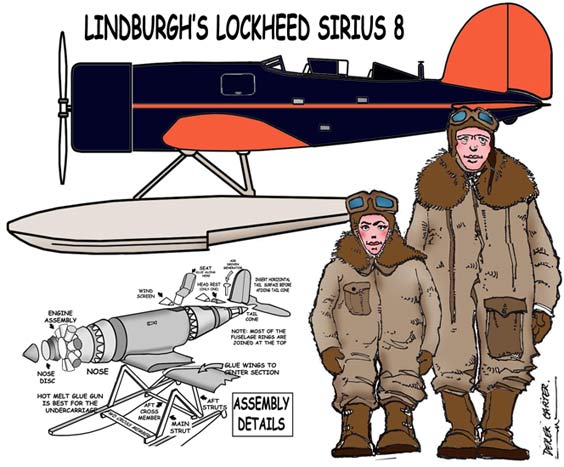

The Lockheed 8 Sirius was single engine, propeller driven monoplane designed and built by Jack Northrop and Gerard Vultee while they were engineers at Lockheed in 1929, at the request of Charles Lindbergh. Two versions of the same basic design were built for the United States Air Force, one made largely of wood with a fixed landing gear, and one with a metal skin and retractable landing gear.

Lockheed - Sirius

Lockheed Sirius Charles Lindbergh's Seaplane

In 1923, the Lindberghs flew the Arctic great circle route from New York to Tokyo, the first time anyone had attempted such a feat, and in just 83 hours air time!! Lindbergh told reporters in Tokyo that the flight had been a "pleasure trip" and added, with his customary exactness, that their altitude had ranged from a high of 7,000 feet to a low of 57. Despite his modest assessment, the Lindberghs' flight was a spectacular one and here's the model... |

|

Previously Charles Lindbergh made famous the Spirit of St Louis, when he was the first to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean..

Pioneering the Arctic in a Lockheed Sirius-8

While Cramer and Gronau were daring the Greenland icecap, the

world's best-known aviator was pioneering the hazardous northerly

course to Asia. Charles Lindbergh and his wife, Anne-whom he had

taught to fly-had worked out an elaborate plan for a flight from the United States to Tokyo, via northern Canada, Alaska and Siberia. The

trip was sponsored by Pan American Airways, which was looking for

overseas commercial routes, and it was marked by Lindbergh's characteristic blend of boldness, originality and painstaking preparation. The

craft chosen was the most advanced long-distance seaplane then made,

a Lockheed Sirius floatplane with a single 600-horsepower Wright Cyclone engine and extra fuel tanks that gave it a 2,100-mile range. It was

fitted not only with blind-flying instruments and a two-way radio-

Anne Lindbergh had acquired an operator's license-but also with a

radio direction finder. This consisted of an antenna and a receiver with

which the Lindberghs could pick up directional signals beamed from

ground stations along their route and thus stay on course. Fuel was

waiting at each scheduled stop, and in case of unscheduled landings,

the Lindberghs carried everything they needed to be self-sufficient.

They calculated that they could fly from New York to Tokyo in 12 hops,

the longest leg 1,115 miles over Canada's unforgiving Barren Grounds.

While Cramer and Gronau were daring the Greenland icecap, the

world's best-known aviator was pioneering the hazardous northerly

course to Asia. Charles Lindbergh and his wife, Anne-whom he had

taught to fly-had worked out an elaborate plan for a flight from the United States to Tokyo, via northern Canada, Alaska and Siberia. The

trip was sponsored by Pan American Airways, which was looking for

overseas commercial routes, and it was marked by Lindbergh's characteristic blend of boldness, originality and painstaking preparation. The

craft chosen was the most advanced long-distance seaplane then made,

a Lockheed Sirius floatplane with a single 600-horsepower Wright Cyclone engine and extra fuel tanks that gave it a 2,100-mile range. It was

fitted not only with blind-flying instruments and a two-way radio-

Anne Lindbergh had acquired an operator's license-but also with a

radio direction finder. This consisted of an antenna and a receiver with

which the Lindberghs could pick up directional signals beamed from

ground stations along their route and thus stay on course. Fuel was

waiting at each scheduled stop, and in case of unscheduled landings,

the Lindberghs carried everything they needed to be self-sufficient.

They calculated that they could fly from New York to Tokyo in 12 hops,

the longest leg 1,115 miles over Canada's unforgiving Barren Grounds.

After flying the Sirius from New York to Washington for clearances and passports, the Lindberghs headed for North Haven, Maine, to say good-by to their infant son, who had been left with Anne Lindbergh's parents. Then they began the trip proper, completing the first day's run on July 31, 1931, in Ottawa, where assorted experts tried to talk them into taking a safer route across the north country. The experts gave up only when Lindbergh threatened to fly to Europe and Asia via the Greenland icecap instead, a far more dangerous proposition. The next day, the pair started north on short flights across Ontario and Manitoba, stopping each night at ever more remote fur-trapping outposts.

On August 2 the Lindberghs reached the Northwest Territories, landing at Baker Lake, a community so isolated that the residents received

their newspapers in batches of 365, one year late. The Lindberghs

brought them up to date on the outside world and the next day took off

for the village of Aklavik, more than 1,000 miles away.

On the flight to Aklavik, Anne Lindbergh got her first intimations of the unknown Arctic. The gray and treeless coast beneath them, she later wrote, "had no reality that could be recognized, measured and passed over. I knew that the white cloud bank out to sea hung over the ice pack-that it marked, like the fiery ring around an enchanted castle, the outer circle of a frozen kingdom we could not enter. " It was 3 a. am. when they landed at Aklavik, waking most of the town and precipitating a chorus of howls from the packs of huskies tethered there.

The couple's first sustained encounter with the maddening mists of the summertime Arctic came on the 550-mile flight over the sea from Aklavik to Point Barrow, Alaska, Hubert Wilkins' old jumping-off point and the northern apex of their course. "Here a cloud and there a drizzle," Anne Lindbergh wrote, "here a wall and there, fast melting, a hole through which gleamed the hard metallic scales of the sea." Then came a climb into "white blankness" with no sight of land or sea or sky. Time and again Lindbergh descended beneath the fog, signaling to his wife to reel in the trailing antenna of their radio. They were flying so near the waves that they risked snapping off the weight at its end. The fog lifted on their approach to Barrow. They landed in a lagoon, got out of the Sirius and were greeted by a crowd of Eskimos "not with a shout," Anne Lindbergh wrote, "but a slow, deep cry of welcome."

At Barrow the Lindberghs learned that the ship en route to the settlement with the year's eagerly awaited supplies, as well as fuel for their plane, was ice-locked 100 miles away, waiting for the wind change that would open the pack and release it. The couple settled in for what would turn out to be a three-day stay, dining their first night on roast reindeer and canned vegetables and offering to help their host with the dishes.

On August 10-one day after Parker Cramer vanished in the North Sea-the Lindberghs decided not to wait any longer for the supply

ship. They had, Lindbergh thought, enough fuel to fly the 520 miles to

Nome. But now they came up against something they had failed to

consider in planning their trip: The long days of the Arctic summer were

beginning to shorten. At 8:30 p.m. they were still two hours short of

Nome when dusk caught up with them, accompanied by fog. The

approach of night over the northern wilderness filled Anne Lindbergh

with "the terror of a savage seeing the first eclipse." A message from the

Nome radio operator promised flares to light their landing, but Lindbergh chose to come down for the night in an inlet rather than risk flying

in darkness and fog over the Brooks Range. After a tricky downwind

landing, the Lindberghs improvised a bed in the plane's baggage compartment. They had just fallen asleep when they were roused with a start

by the sound of someone calling them. They looked out and saw beside

the pontoons two small boats roofed with skins. From inside the boats

stared Eskimo faces. "Hello," one of the visitors said. "We hunt duck."

Lindbergh replied brightly, "Get many ducks?" With this, the conversation stalled, and the aviators went back to bed.

On August 10-one day after Parker Cramer vanished in the North Sea-the Lindberghs decided not to wait any longer for the supply

ship. They had, Lindbergh thought, enough fuel to fly the 520 miles to

Nome. But now they came up against something they had failed to

consider in planning their trip: The long days of the Arctic summer were

beginning to shorten. At 8:30 p.m. they were still two hours short of

Nome when dusk caught up with them, accompanied by fog. The

approach of night over the northern wilderness filled Anne Lindbergh

with "the terror of a savage seeing the first eclipse." A message from the

Nome radio operator promised flares to light their landing, but Lindbergh chose to come down for the night in an inlet rather than risk flying

in darkness and fog over the Brooks Range. After a tricky downwind

landing, the Lindberghs improvised a bed in the plane's baggage compartment. They had just fallen asleep when they were roused with a start

by the sound of someone calling them. They looked out and saw beside

the pontoons two small boats roofed with skins. From inside the boats

stared Eskimo faces. "Hello," one of the visitors said. "We hunt duck."

Lindbergh replied brightly, "Get many ducks?" With this, the conversation stalled, and the aviators went back to bed.

They reached Nome safely in the morning and took on a full load of fuel for the 1,000-mile over water flight to their next refueling point, the Siberian island of Karaginski. When they arrived there on August 15, they were greeted by fur trappers and a small, orphaned brown bear that served as the local pet. Their hosts fed them wild strawberries and milk and informed them that it was now Saturday, August 16, instead of Friday, August 15. \

Having crossed the 180th meridian-the international date line-the Lindberghs had lost a full day. The next day they flew south to Pgtropavlovsk, a fishing village on the coast with a beautiful deep harbor and, on the hills that rose from it, houses brightly painted in traditional Russian style. They lingered for three days, pre- paring for the thorniest part of their course, a long southerly passage over the notoriously foggy Kuriles, the chain of islands linking Siberia's Kamchatka Peninsula to Hokkaido, Japan's second largest island.

The Kuriles lived up to their billing, and the journey was frightening,

although the Sirius was guided by Japanese radio operators most of the

time. About halfway along the 1,000-mile stretch the Sirius hit a wall of

fog that concealed the mountains, making an immediate descent essential. Anne Lindbergh watched her husband push back the cockpit cover

and don his goggles, "the familiar buckling on of armor" that signaled

another joust with the elements. Alternating between visual and instrument flight, Lindbergh groped his way down through the mist, skirting

the mountains in search of a patch of sea to land on. Finally, after several

tries that left his wife white-knuckled and momentarily determined to fly

no more, he found a hole in the fog and dived for it, leveling off just

above the water and landing with a series of bounces that buckled the

spreader bars between the pontoons. They were at Ketoi Island, 100

miles northeast of Brouton Island, where their fuel was stored.

The Kuriles lived up to their billing, and the journey was frightening,

although the Sirius was guided by Japanese radio operators most of the

time. About halfway along the 1,000-mile stretch the Sirius hit a wall of

fog that concealed the mountains, making an immediate descent essential. Anne Lindbergh watched her husband push back the cockpit cover

and don his goggles, "the familiar buckling on of armor" that signaled

another joust with the elements. Alternating between visual and instrument flight, Lindbergh groped his way down through the mist, skirting

the mountains in search of a patch of sea to land on. Finally, after several

tries that left his wife white-knuckled and momentarily determined to fly

no more, he found a hole in the fog and dived for it, leveling off just

above the water and landing with a series of bounces that buckled the

spreader bars between the pontoons. They were at Ketoi Island, 100

miles northeast of Brouton Island, where their fuel was stored.

The Lindberghs spent a rough night in the wave-rocked Sirius, waking in the morning to find the ship Shinshuru Maru, sent by the Japanese government, standing by to assist them. Sailors helped Lindbergh repair the plane and then towed it to the calm waters of Brouton Bay.

One day later, the Lindberghs took off for Nemuro, on the eastern tip of Hokkaido. Relentless fog and rain forced the plane down twice en route. One landing was at a tiny willow and pine-covered island called Kunashiri, where three of the inhabitants-a fisherman, his father and his son-fed them and courteously sent them on their way. On August 23 the Lindberghs finally arrived in Nemuro, where a crowd of 10,000 welcomed them. The unshaven pilot and his first mate were "dirty, as you see," he said to the assembled newspapermen, "but not tired." He let it be known that he appreciated the fine weather "because we had only a half-hour's gasoline left." After refueling, the Lindberghs flew on to Tokyo, there to be greeted by another throng.

The Lockheed Sirius Tingmissartoq:

Perhaps the most famous seaplane conversion from an

aircraft not normally used as a seaplane was the Lockheed Model B Sirius that was named Tingmissartoq - the

Inuit word for "one who flies like a bird" - by a boy

in Greenland. What made the moment of this

naming particularly romantic was the fact that

this particular Sirius was in Greenland as part of

a historic flight by Charles Lindbergh and his

wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh. It was also  the

aircraft that was celebrated in Anne's best-selling

book North to the Orient.

the

aircraft that was celebrated in Anne's best-selling

book North to the Orient.

The Model 8 was 27 feet 1 inch in length, 9 feet 3 inches high, and had a wing span of 42 feet 9.25 inches. It weighed 2,978 pounds empty, and had a gross weight of 4,600 pounds. The Sirius was powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1340 Wasp radial engine rated at 450 horsepower. This powered the aircraft with a top speed of 185 mph, and a cruising speed of 150 mph. It had a range of 975 miles.

In 1931, with the aircraft retrofitted in seaplane configuration, Charles and Anne boarded their Sirius and made the flight to the Far East that would be described in North to the Orient. They island-hopped across the North Pacific to Japan through Alaska and the Aleutian chain, and traveled into China, evaluating potential airline routes. Damaged in Hankow, the Sirius was returned to Lockheed for rebuilding and installation of a 710-horsepower Wright SR-1839 Cyclone engine.

In July 1933, the legendary aviator and the best-selling author embarked on another airline survey flight. This time, the Lindberghs headed out across the stormy North Atlantic on the route that made Charles a household name in 1927. Indeed, the scope of this flight was far more ambitious than Lindbergh's legendary New York-to-Paris solo flight. Instead of simply crossing the Atlantic, he and his wife would set out to circumnavigate a sizable portion of it, looking at potential crossing routes in both the North Atlantic and the South Atlantic. It was during their refueling stop in Angmagssalik, Greenland, on their outbound leg that Tingmissartoq got its name. Plane and crew continued through Europe to Moscow on their much-publicized tour. From Europe, the Sirius carried them south across Africa to Gambia, from which they crossed the South Atlantic to Brazil. Tingmissartoq appeared in the sky over New York on December 19, 1933, as the city turned out to welcome the Lindberghs. The aircraft, like its crew, had earned a place in history.

Steelcraft Lockheed Sirius pedal airplane from the 30s |

Lindbergh's Lockheed Sirius Model made from mahogany. |

The pilots view of the Lockheed Sirius cockpit. |

|

The Lockheed Model 8 - called Sirius after the brightest

star in the sky - was created by Jack Northrop when he

was an engineer at Lockheed. Designed initially as a land-plane, it made its first flight in 1929. With Lindbergh as the

first customer, a dozen further orders came falling in. What a wonderful era that must have been!! |

|

|

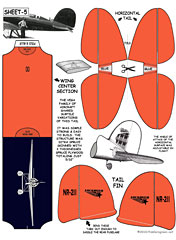

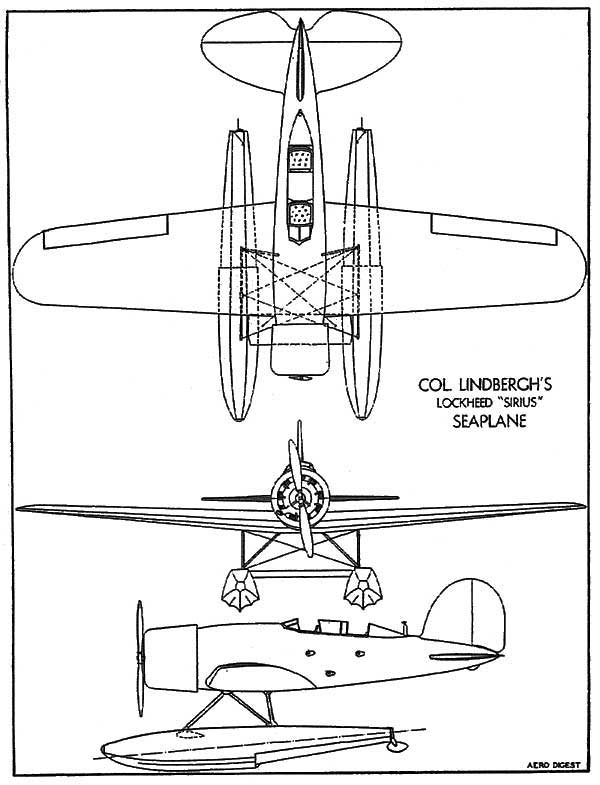

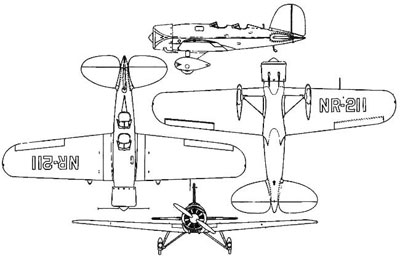

3 View of Lindberghs Lockheed Sirius 8 taken from a 1931 Aero Digest. |

Specifications for the Lockheed Sirius 8

|

Dimensions |

The Lockheed Sirius 8 exhibited at the EAA air Show, Oshkosh, WI |

The same Lockheed Sirius now exhibited at the NASM in Washington |

|

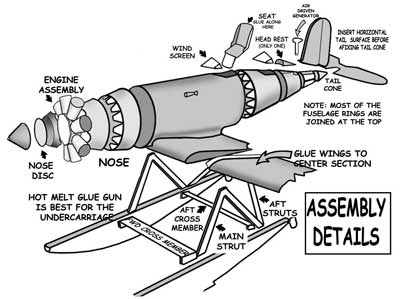

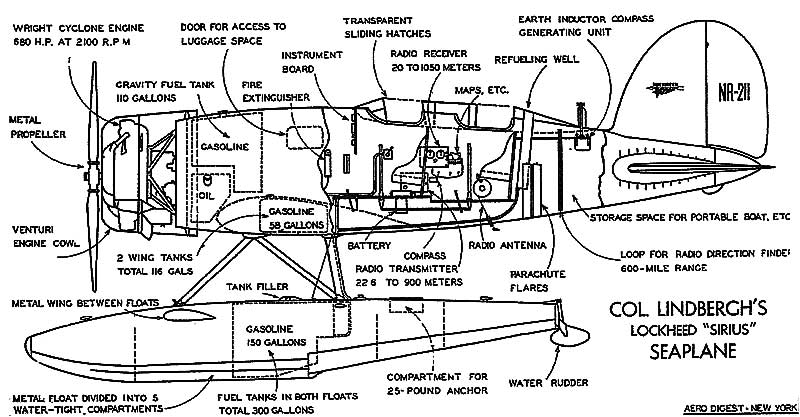

This Cutaway of Lindbergh's Lockheed Sirius was taken from a 1931 Aero Digest |