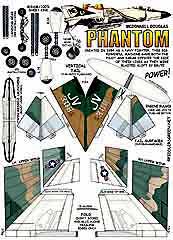

The McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom

This webpage is for the single F-4 Phantom, the F-4 Phantom Collection which has 9 different versions.

Click HERE to get to the F-4 Phantom Collection model offer

Even before the 5,000th McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II was delivered in mid-1978, the aircraft had a production history which far outstripped that of any other recent combat jet aircraft in the Western world.

The Phantom's success, originally attributable to its excellent fighter and strike aircraft qualities, was boosted by the demand for the type during the Vietnam war. During 1967 the production rate at McDonnell Douglas's St Louis factory peaked at 72 aircraft per month.

The Phantom has been used as a front-line aircraft by 12 nations-and remains in service with 11 countries.

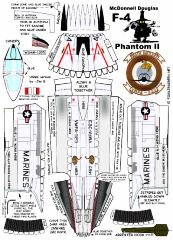

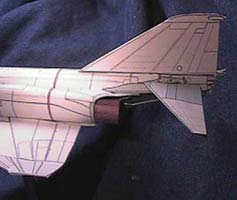

His buddy Rob emails.. "I really liked

the model of the F4 you sent out last year, but was disappointed

that it was not the Naval version, being an old phantom

phixer .However, with a little bit of jiggling, like shortening

the nose and using a set of drawings I had left from my

tour with the Blue Angels, I came up with a pretty good

facsimile. I screwed up the writing on the originals pretty

badly and added a few things like dummy sparrow missiles,

which were actually tanks for the oil and dye used for smoke

during the shows. We removed the forward fins on the forward

missiles for ease of access to the pneumatic system.

A little on nomenclature. The horizontal stabs were called

stabilators, since they were hardly horizontal. The intake

"baffles" were called ramps (variable inlet ramps, actually).

Thanks for all the fun so far." Rob Carleen

I was thrilled about the Phantom model in it's early stage. Ibit my tongue and hoped it would become available soon. It is more than worth the wait. Someone said 2001 would be a good year for models and it's a model like the Phantom that makes it so good. Thanks kindly, I appreciate the hard work it took to make it . Please thank your other designer for me as well. Take care ..Peter H 3/22

I can't tell you how much enjoyment I get from making these models. Keep up the great work.It should be very gratifying for you to know how many people you please by the work you do! Meaning and purpose in life. That's what it's all about.And you achieve both with your efforts. Thanks again ..Gerry (3/22)

What a beautiful little work of art it is. Once I get done building the ME-262 in 1:144 scale, I'll have to give it a shot. Roger 3/23

I really enjoyed making the F-4, the way it same together was amazing. I'll send you a photo of it soon. I modified it so that it can ride on top of one of my rockets so it will glide back to earth. I was impressed with the look of it in general. Sam (3/28)

Just put a message about you on our JROTC website message board. Don't be surprised if you get quite a few units asking for info. There are over 700 Air Force JROTC units around the country and world ......Scott McElvain

Phantom Phlyers

With the first flight of the F-4, on May 27, 1958, Navy pilots felt

that they had a real winner for a change. Many early problems

were uncovered, and were resolved. Lateral control in slow speed

flight was poor, but was corrected by the addition of BLC, or

Boundary Layer Control.

With the first flight of the F-4, on May 27, 1958, Navy pilots felt

that they had a real winner for a change. Many early problems

were uncovered, and were resolved. Lateral control in slow speed

flight was poor, but was corrected by the addition of BLC, or

Boundary Layer Control.

With BLC, air is bled off the engine compressors, led through ducts to the wings and vented into the boundary layer air over the leading and trailing edge wing flaps. Radar antenna size was increased, which forced a fe-design of the radome, and gave the Phantom 11 its nose heavy ugliness. The rear cockpit needed more headroom, so new raised profile canopies were installed.

A better ejection seat became available from Martin-Baker, in England, and was incorporated into the design. Other smaller troubles were encountered and overcome, during extensive testing at the Navy's Patuxent River, Maryland,center and on board the fleet aircraft carriers.

Well before the fleet sailors had their hands on the plane, it had already re-written most of the world's records for speed and altitude. When it did arrive in the Fleet, the effect of the Phantom ll was electric. Navy fighter pilots, traditionally accustomed to a second-best airplane because of carrier landing and take-off limitations, had, for the first time, the world's finest by far.

An important part of the F-4 missile shooter concept called for a Naval Flight Officer to man the rear seat. These officers, full time radar trained weapons system specialists, were to make up a new breed in naval aviation ranks.

The mastery of the Phantom is a truly dual achievement. Without

a pilot, the Phantom is strictly no-go. Without a flight officer,

the F-4 is largely just another piece of aerial transportation.

The flight officer handles the navigation, the communications,

and, in many cases, the in flight coordination, while also providing

significant assistance in the weapons delivery phase itself. In

the interceptor role, it is the flight officer who does the radar

searching, and makes the system acquisition of the target.

The mastery of the Phantom is a truly dual achievement. Without

a pilot, the Phantom is strictly no-go. Without a flight officer,

the F-4 is largely just another piece of aerial transportation.

The flight officer handles the navigation, the communications,

and, in many cases, the in flight coordination, while also providing

significant assistance in the weapons delivery phase itself. In

the interceptor role, it is the flight officer who does the radar

searching, and makes the system acquisition of the target.

Although the Phantom's weapons system is a highly automatic one, alternate procedures are incorporated into almost every phase of its operations which permit manual control by the flight officer for most of the normally automatic functions. In practical terms, this permits the flight officer to substitute his own judgment and his own proficiency whenever he feels that the automatic features are either not up to snuff or being decoyed by counter-measures. This great advantage is realizable only with an intelligent, capable, motivated and well trained young man.

In developing this type of talent, the Navy and the Air Force have proceeded along slightly different paths, in consideration of the differing nature of missions in their operations. The Navy uses volunteer college graduates who meet all the basic officer requirements, plus special aeronautic qualifications. After appropriate training, they become designated Naval Flight Officers.

The USAF uses rated pilots, who receive additional radar systems

training subsequent to flight training. Inter-service debate has

been fairly heated on the merits of each system, but the fact

is that the Navy's primary F-4 mission is that of interceptor,

where the full-time radar expert pays off. The Air Force tends

to equate the air superiority and attack missions, and feels,

quite properly, that a second pilot with radar training is a better

bet for these tasks.

Each Phantom aircrew develops its own peculiar brand of cooperation, which fits into a combined personality of the two men. Some pilots are great "radar heads" from past experience in single place fighters. Because the F-4 pilot has a beautiful repeater radar scope right in front of him, he can pick up targets almost as soon as the flight officer. A "radar-headed" pilot with a forceful personality can drive a retiring Flight Officer out of his mind in nothing flat, just by needling and second-guessing the radar operation. Some pilots are real wild blue yonder types, who, initially, don't care to understand about radars. This fellow invariably has a fine set of eyes, "leaves the radar to George" in the back seat, and is from Missouri anyway. He doesn't trust a TV tube, and won't really believe anything unless he can see it himself. He can drive a good conscientious Flight Officer crazy by refusing to turn and attack on radar knowledge, by delaying until he can "see" the target for himself, or by forcing the flight officer to describe repeatedly what is already literally staring him in the face from his own scope.

Flight officers, on the other hand, are far from lily whites. A slow and fumbling performance during an intercept by a flight officer can turn an old "radar-headed" pilot almost apoplectic in a matter of seconds. In this case the pilot knows damn well that he could do better all by himself, and bewails the fact that so few radar controls are in his cockpit.

Another flight officer who can send a pilot into frenzy is the "tourist" type. This fellow, usually an art or music major in college, is simply along for the ride. He sits blithely in the rear enjoying the golden hues of the breaking dawn, or the tortuously slow boiling of gathering bright white cumulus clouds, or the sinuous shadowy blackness of a jet contrail as seen from above. "Targets? Radar? Oh, yes-that stuff . . ."

Many flight officers are initially attracted to the job by

a love of electronics, tinkering where it isn't necessary. Unless firmly disciplined quite early in

their training cycle, they can become twiddlers and tweakers and

can also drive good pilots to drink. They are never ever fully

satisfied with the radar, and keep twirling knobs and checking

switches and experimenting with the picture. They just refuse

to let a good set operate without some additional "fine tuning"

which often as not, screws up the whole operation in the long

run.

For inter-cockpit communications, either a hot or cold mike operation is possible. With "hot mike," the aircrew can freely talk together, just as two people would over a telephone. This provides all the advantages of instant availability, but it can be noisy and bothersome, particularly when a poorly operating oxygen regulator lets the sounds of breathing get onto the wires. You get to know your flying buddy quite well when you have to listen to his every breath, inhaling and exhaling, over several hours! This feature, very troublesome in early Phantoms, started a whole series of ready room jokes about Gaspers, Wheezers, Garglers, Whistlers, Grunters, and Moaners.

One very young Phantom flight officer, on his first ride, suddenly let go with an ear splitting roar as the pilot instructor was demonstrating a high "g" turning maneuver. The pilot, momentarily deafened by the blast resounding in his ears, was sure that some horrible accident had occurred back aft. He immediately headed for home, broadcasting Maydays en route, and landed as rapidly as he could. Shutting down at the runway's end, he clambered back to the rear cockpit to find the hale, hearty, but thoroughly bewildered young fellow sitting there.

"What in hell was that roar about?" the outraged instructor demanded.

"Oh, that, sir," breathed the cherubic Ensign, "They told me at Pensacola that I could take more "g"s by making my stomach muscles hard, and that shouting was a good way to do it."

|

Dave |

Then, too, there are the nervous Nellie's, who come in either pilot or flight officer garb. Nellie's constantly check the other fellow, or the fuel, or the radios, or the weather. Prudent they are, but fun they ain' t! Listen to one of these doomsayers over an intercom for a couple of hours and you find yourself almost wishing that something would go berserk, just to satisfy the old worrywart!

Surprisingly enough, most Phantom aircrews adapt to each other

at a very rapid rate. Nervous Nellie's are calmed by flying tourists.

A wild blue yonder type learns respect for bespectacled George

after he's been led to a few unseen targets by radar, and a fumbling

tweaker is turned into a real pro by the verbal lashes of a

radar-headed

old timer. In actual practice, most pilots and flight officers

select their own partners, and crew integrity is maintained to

the fullest possible limit. These choices are made on the basis

of mutual respect, which is also the soundest  foundation for lasting

friendship. Because they are all fine and fearless people to begin

with, because they are young and pliable, because they understand

the complete reliance they must have upon each other, because

they learn to appreciate the other fellow's problems as well as

their own, and because they both realize what a tremendous bird

the Phantom is, they quickly adapt-giving and taking here and

there-trying harder to do their own jobs better-building a mutual

respect which can't be shaken.

foundation for lasting

friendship. Because they are all fine and fearless people to begin

with, because they are young and pliable, because they understand

the complete reliance they must have upon each other, because

they learn to appreciate the other fellow's problems as well as

their own, and because they both realize what a tremendous bird

the Phantom is, they quickly adapt-giving and taking here and

there-trying harder to do their own jobs better-building a mutual

respect which can't be shaken.

For an older squadron commander, the most rewarding part of his job comes in overseeing the formation of these relationships. The pilots and flight officers are largely young men, in their early 20's, with precious little experience or responsibility behind them. When they are assigned to a squadron, and a $3 million airplane and another man's life are entrusted to their care, they mature at an astounding rate. Real professionalism develops apace with true friendships. Where else can a young man find a greater challenge?

Just like other new products, new airplanes need publicity gimmicks to accompany their introduction. For the men who were to maintain and fly the F-4 Phantom, a new Phantom language was the gimmick used for flight jacket patches, decals and the like. Pilots were Phantom Phlyers, Flight officers became Phantom Pherrets, and the maintenance gang were Phantom Phixers.

Late one summer night in 1962, in the Mediterranean Sea, a signalman on the bridge of the USS Forestall smiled ruefully as he wrote down the message coming by flashing light from Forestall's nuclear powered sister super-carrier Enterprise...

PHIGHTING SQUADRON 102, THE WORLD'S PHINEST PHIGHTER SQUADRON, PHLEW PHIPHTY-PHIVE PHLAWLESS PHANTOM PHLIGHT HOURS TODAY.

This was another of those crazy Phantom language messages, more proud boasting from Enterprise's brand new F-4 Phantom 11 fighter squadron to needle the equally new F-4 squadron in Forestall. In those days, outside of aviation circles, few people either knew or cared what a Phantom 11 was. But by the middle of 1966, rarely a day went by without a newspaper headline citing some new achievement of the fabulous Phantom over the skies of Vietnam.

Carrier Launch

Because the Phantom was Navy designed and Navy sponsored, its infancy was spent on Navy carrier decks. A carrier flight deck is one of the dirtiest, yet most colorful places in the world. The dirt is ever-present. Its sources are legion. Particles of stack gases from deep in the ship's boiler fires- tiny particles from jet engine exhausts, rubber from airplane tires, oil and grease and hydraulic fluid from airplane servicing spills, the ever present muck and dirt of the yellow equipment-the starters and tractors and cranes, odd nuts and bolts and cotter pins long since buried in a crevice, suddenly broken free by some shake or roll of the ship, pieces of line and wire and chains used in tie-downs, slivers of wood from broken wheel chocks, candy wrappers and wooden ice cream spoons and cigarette butts and debris from pockets-pencils and keys and knives and dzus button wrenches, paper scraps and rags, rags, rags, all of it liberally spiced with encrusted salt from the sea spray and greasy residue of steam from the catapult seepage.

It is unbelievable that such an assortment of junk could stick

to a flat deck over which 30 to 40 knots of clean, fresh, ocean

winds flow most of each day. Yet mass "walk-downs" conducted

by dozens of sailors walking shoulder to shoulder over the length

of the deck, prior to flight operations, can and do result in

literally boxes full of debris-all of which is called FOD, short

for Foreign Object Damage. Once the FOD hunt is completed, the

casual observer would rest assured that that deck was clean. The

engines are started, jet blasts whirl around the deck, the ship

turns into the clean breeze, and all sorts of debris-rags, papers,

and pencils come hurtling down the deck, bouncing aft to drop

into the sea astern. New air bosses, the senior Commanders perched

high above the deck in Pri-Fly whose responsibility it is to

run the show have been known to foam at the mouth when the hail

of FOD starts. Older, wiser air bosses don't look, since it all

subsides within a few seconds anyway!

During this pre-flight period, all sorts of radios and intra-ship communications come to life. Reports are made on the various pre-flight checks of the aircraft. They are either up or down. If up, they are brought to the catapult in an established sequence and launched on schedule. When one goes "down" as it can at almost any instant prior to the salute on the cat, a flurry of signals and orders and actions follow. The sick airplane must be threaded out of line, onto an elevator and run below. A standby, far back in the pack, must be brought forward as a replacement. With small airplanes like the A-4, and large decks, like the Enterprise's, this is no great problem. With a large airplane, like the A-3, and a small deck, like the Hancock's, the evolution is aptly called an "elephant dance."

The Phantom aircrew takes a good 10 to 15 minutes just to man the machine, strap in, and get the many systems checked out. As soon as the air boss orders, 'Start engines," over the ear-splitting bull horn, the Phantom crew begins an intricate ritual of pre-launch activity. The plane captain in brown helmet, runs forward of the parked plane and gives a series of arm and- hand signals to start the engines, unplug the starters, spread the wings, lower the flaps, check the operation of the ailerons, horizontal stabilizer, and rudder, tail hook, speed brakes, the emergency drop-out generator and the in-flight refueling probe. Every signal has a specific meaning. Swinging both extended arms over his head from a crossed position to a horizontal one means to spread the wings. Holding one arm up, elbow bent 90 deg, and touching the underside of that elbow with the palm of the other hand means to drive home the wing locking pins. Flaps are extended by splitting two arms forward of the body, half flaps by following this quickly with crossed index fingers, tail hook by giving an exaggerated thumbs down or thumbs up, swinging the arm from the shoulder. Refueling probe is extended by one arm slowly swung way out to a side. Emergency generator drops out by a sweeping gesture with both hands and a split of the hands, and so on.

Many plane captains are pantomime hams at heart, and add a few peculiar whirls and flourishes to each signal. With checks completed, the plane captain turns the airplane over to a yellow-shirted Flight Deck Director, who has another assortment of hand and arm signals . . . chocks out, taxi forward, turn left, turn right, speed up, slow down... all are signaled in rapid succession as the Phantom rolls out of its parking place, onto the traveled section of the flight deck, and moves forward toward the catapult.

Here now, the Flight Deck Ballet really gets going. Plane directors remain in one general area, even though they dance around a lot while so doing. They brace themselves, backwards, against the normal wind over the deck, and have to move quickly to avoid the hurricane force of exhausts from other planes forward. While bracing- really clinging with toes and heels and leaning backwards-they have to use both hands over their heads to effect the signals for the pilot to follow. A come ahead is just that . . . both hands high, motioning come along. Turns are signaled by making a fist with one hand and jabbing it downward, while still keeping the come ahead signal active with the other. Modest, rather than furious, signals mean modest turns.

|

|

Directors are yellow-clad, from helmet to waist. A certain number have earphones in their bulky cloth helmets, through which they receive radioed orders from Pri-Fly, the Flight Deck Bos'n or the Flight Deck Officer. Clinging to each strut, chock in hand, are the blue-shirted plane handlers, who also follow each signal from the Director. If a sudden skid develops they throw the chock around the airplane wheel. As the Director dances backward, moving the plane forward, he nears the edge of his area of responsibility, and passes the control along to another yellow-shirt farther up the deck.

Ultimately, it is the Catapult Plane Director who does the fine signaling required to bring the huge Phantom directly over the catapult shuttle for hook up. As it moves into position, other crewmen feverishly scramble around beneath the plane, fixing the heavy steel bridle to the plane, and the dumbbell shaped hold back to a fitting in the stern keel of the bird. Their work is dangerous and demanding. The noise level alone is so high that words are useless. The plane's wheels are rolling inches from them, engines screaming away with a searing exhaust blast just above their heads, wind pummeling them and making any footing uncertain, and a freshet of steam enveloping them all the while, fogging their protective goggles and adding a sense of surrealism to the scene.

Catapult hook-up men never walk, or run, or even crawl. They just scramble and roll like agitated monkeys. With the Phantom in place, a slight tension is placed on the catapult bridle, straining to pull the plane forward hard against the hold back dumbbell. The pilot extends the nose gear on signal, which whooshes the nose of the airplane six feet or more into the air. Flaps are set as required, and the catapult officer extends two fingers and rapidly rotates his hand over his head. From here on, until airborne, the Phantom crew is in the hands of the cat crew. Feet come off the brakes, engines are turned up to full power, hook-up men scramble to the catwalk, the plane shudders and shakes as 34,000 lbs of thrust strains mightily against the holdback.

When the pilot gets an O.K. check from his flight officer, and when he is satisfied that his engines are cranking up as they should, he salutes smartly with his right hand, returns it to the stick, jams his elbow back, all the while keeping his left arm thrust full forward, holding the throttles with the heel of his hand and grasping a retaining handle with his fingers. He puts his head firmly against the headrest and waits . . . and waits . . . and waits. Now every second seems like an eternity. The view ahead is of water-miles and miles of slate-gray sea. The very forward tip of the flight deck is barely visible, only yards ahead. Power strains against its leash. The catapult officer swings his arm in a high arc, touches the deck and the cat operator in the catwalk throws the firing lever. Within a split second, the cat fires!

Motion starts so suddenly that breath stops. Everything is forced aft with tremendous "g" as the heavy Phantom is accelerated from 0 to 120 knots in less than 300 feet. The sensation for the aircrew during these brief seconds of maximum longitudinal acceleration is best described as breathless. No carrier aircrew does more than gasp during the cat stroke. It's just a bang and a whoosh, all together. Vision is blurred as the reds, blues, yellows, greens and browns of the flight deck crew become a streak of peripheral gray. The airplane itself seems to scream in agony as each bolt, each plate, each screw and pin and washer and rivet is put under maximum strain. The tires flatten to the rims even with 450 pounds of inflation!

As the plane is literally flung into the air, the "g" subsides with a lurch, and flight begins. In spite of the Phantom's excellent flying qualities, these few seconds of initial flight after a cat shot demand the utmost in pilot skill. This period, called "rotation off the cat" can be a truly fearsome experience and provides some of the greatest "hairy tales" of all military flying.

It comes about in an extreme point of the design compromise envelope. The Phantom's wings are highly swept. To fly at very slow speeds, they have to be rotated to a very nose-high attitude. This is no problem in landing, where this rotation is a slow, easily controlled evolution, nor does it create any hazardous field takeoffs, where, again, the transition is relatively slow. But, when heavily loaded, and coming off a four second cat shot the rotation has to be quick, positive and precise. Too little back stick means a settling problem, and the sea is only 60 feet below. Too much, on the other hand, puts the wings into a condition near stall, where control is far less positive, and where subsequent settling is possible regardless of engine power.

In daylight, or on nice clear nights, the pilot gets both peripheral visual clues and gyro horizon indications to aid him in establishing just the right amount of nose up attitude. But on a good black night, with no visual horizon of any sort, the gyro horizon becomes almost the only clue. The force of the catapult stroke practically flattens the eyeballs so that even seeing this instrument, much less interpreting its finer details, is a momentary problem.

The pilot error, when it is made, is generally on the side of over-rotation, throwing the plane into a very steep, dangerous, climbing attitude at low speed and low altitude. To correct, as he must, the pilot rams the stick forward, which pitches the nose downward, and puts negative "g" on the crew. If you haven't experienced negative "g" while trying to fly instruments in a tight situation on a black night, you just haven't lived! It's the most excruciating feeling imaginable! Nothing else can compare with it. You lift off the seat a bit, your feet get light on the rudders, your arm has to reach farther for the stick, and that just doesn't feel right.

Anything loose in the cockpit, like old pencils or small nuts or: dirt comes flying up in your face and rattling off the canopy; if your helmet isn't tight, it tends to rotate down on your forehead, giving you a feeling of impending blindness, and your middle ears, by which you instinctively measure up, down and left and right, are filling your brain cells with wholly erroneous distractions. Then too, there is an element of sheer terror since you and your flight officer may well be only a few seconds from a watery grave. Over it all, however, is the anger you feel at yourself, for having erred in the first place. Needless to say, over-rotation off the cat is not a continuing problem. No pilot does it more than once.

A spectator's first view of a Phantom night catapult shot is pretty impressive. The twin afterburners light up the flight deck, then go roaring off in a misty cloud of steam and quickly fade into another of the stars. A minor catapult bridle problem existed with the early F-4s. The center line external fuel tank was sometimes "holed" on the catapult shot. Fuel vented into the afterburner wake and lit off in a high trailing spume of fire which made the F-4 look like a Saturn liftoff at Cape Kennedy. The flames were no hazard, but the view from the carrier deck was truly spectacular!

|

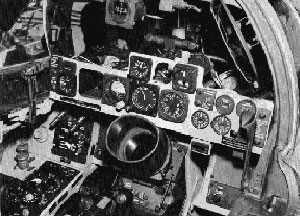

McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom Front Cockpit. |

|

McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom Rear Cockpit |

|

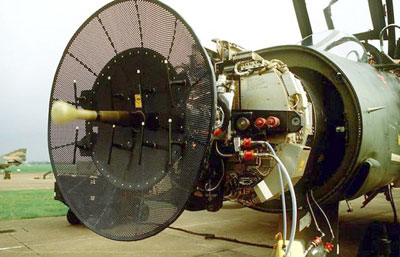

McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom Radar. |

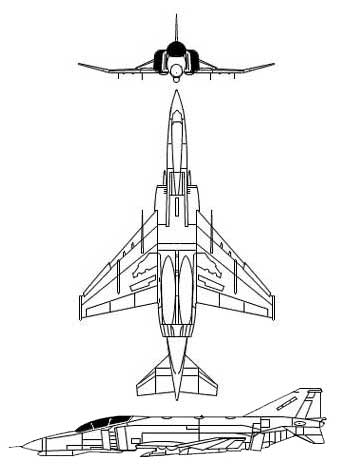

Specifications (F-4E)

Crew: 2 Length: 63 ft Wingspan: 38 ft 4.5 in Height: 16 ft 6 in Wing area: 530.0 ft² Airfoil: NACA 0006.4-64 root, NACA 0003-64 tip Empty weight: 30,328 lb Loaded weight: 41,500 lb Max takeoff weight: 61,795 lb Powerplant: 2× General Electric J79-GE-17A axial compressor turbojets, 17,845 lbf each Zero-lift drag coefficient: 0.0224 Drag area: 11.87 ft² Aspect ratio: 2.77 Fuel capacity: 1,994 U.S. gal internal, 3,335 U.S. gal with three external tanks (370 U.S. gal tanks on the outer wing hardpoints and either a 600 or 610 U.S. gal (2,310 or 2,345 L) tank for he centerline station). Maximum landing weight: 36,831 lb |

Performance Maximum speed: Mach 2.23 (1,472 mph) at 40,000 ft Cruise speed: 585 mph Combat radius: 422 mi Ferry range: 1,615 mi with 3 external fuel tanks Service ceiling: 60,000 ft Rate of climb: 41,300 ft/min Wing loading: 78 lb/ft² lift-to-drag: 8.58 Thrust/weight: 0.86 at loaded weight, 0.58 at MTOW Takeoff roll: 4,490 ft at 53,814 lb Landing roll: 3,680 ft at 36,831 lb Armament Up to 18,650 lb of weapons on nine external hardpoints, including general purpose bombs, cluster bombs, TV- and laser-guided bombs, rocket pods (UK Phantoms 4 × Matra rocket pods with 18 × SNEB 68 mm rockets each), air-to-ground missiles, anti-runway weapons, anti-ship missiles, targeting pods, reconnaissance pods, and nuclear weapons. Baggage pods and external fuel tanks may also be carried. 4 × AIM-7 Sparrow in fuselage recesses plus 4 × AIM-9 Sidewinders on wing pylons; upgraded Hellenic F-4E and German F-4F ICE carry AIM-120 AMRAAM, Japanese F-4EJ Kai carry AAM-3, Hellenic F-4E will carry IRIS-T in future. Iranian F-4s could potentially carry Russian and Chinese missiles. UK Phantoms carry Skyflash missiles[109] 1 × M61 Vulcan 20 mm (.79 in) gatling cannon, 640 rounds 4 × AIM-9 Sidewinder, Python-3 (F-4 Kurnass 2000), IRIS-T (F-4E AUP Hellenic Air Force) 4 × AIM-7 Sparrow, AAM-3(F-4EJ Kai) 4 × AIM-120 AMRAAM for F-4F ICE, F-4E AUP (Hellenic Air Force) 6 × AGM-65 Maverick 4 × AGM-62 Walleye 4 × AGM-45 Shrike, AGM-88 HARM, AGM-78 Standard ARM 4 × GBU-15 18 × Mk.82, GBU-12 5 × Mk.84, GBU-10, GBU-14 18 × CBU-87, CBU-89, CBU-58 SUU-23/A 20 mm (.79 in) Gunpod |

|

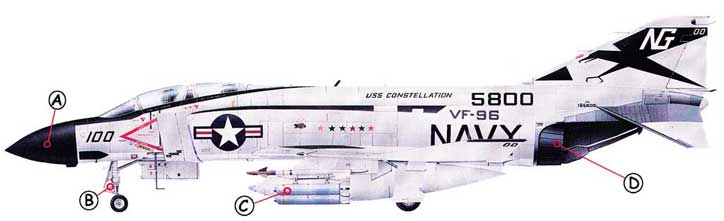

||

| A: Two crewmen meant an extra pair of eyes, which was a real advantage in a close-range, visual dogfight. | B: For protection, the F-4 was fitted with a radar-homing and warning system that detected enemy-surveillance and fire- control radars. The antennas were housed in the tip of the fin. | C: For air-to-air work, the Phantom carried four short-range heat-seeking Sidewinders on the wing pylons. |

|

|||

| A: The Phantom had a superb radar in the shape of the APG-59. This was the best in the world at the time and could track both low- and high- altitude targets. | B: To launch the F-4 was hooked to the catapult with a heavy cable bridle, which fell away when the aircraft left the deck. | C: To highlight the secondary attack role of the Phantom, this aircraft carries cluster bombs. | D: The jetpipes of the Phantom were angled down to give an extra punch for carrier takeoffs. The arrester hook for stopping the aircraft was between the two engines. |

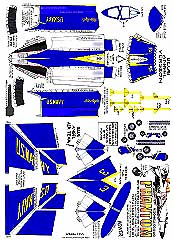

I've been building Fiddlersgreen models for years now, and just tried my hand at a repaint. I noticed there have been very few models done in Israeli Air Force colors and decided to try and do something about it. I settled on the F-4, and attempted to give it an IAF scheme with squadron insignia from the "Knights of the Orange Tails". I'm open to critiques, this is my first and I want to get it right! In the past I've had issues with color matching between my screen and the printed product, so I scanned some printed colors and used them for the repaint. - Ryan Stanley |

|

Seoul, April 7, 2008. South Korean Air Force's RF-4C, the photographic reconnaissance version of the F-4 Phantom fighter jet, crashed in a mountainous area during a pilot training mission and two pilots on board ejected safely just before the crash. |