North American B-25 Mitchell

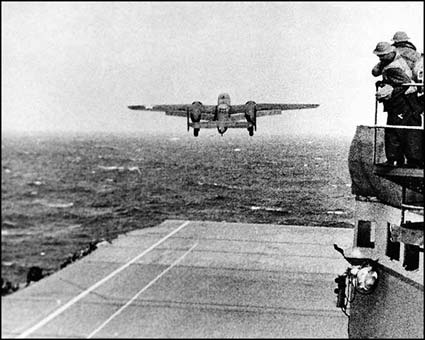

Jimmy Doolittle's North American Mitchell B-25

One of the best light bombers of World War II. It was named after General Billy Mitchell who, as far back as 1920, had the foresight to urge the U.S. to build a stronger and better-prepared air force. On the day that Pearl Harbor was attacked, only 40 B-25s were in service, but before the end of the War more than 11,000 were operating on all fronts in almost all Allied air forces, achieving extraordinary feats.

One of these was the bombing of Tokyo on April 18, 1942, by16 B-25 Mitchells which took off from the carrier Hornet commanded by the ex-sports pilot Jimmy Doolittle. After completing the mission the aircraft landed in China.

|

| Arriving at it's target, Lt. Ted Lawson's B-25B commences it's bombing run in "30 Seconds over Tokyo" by Craig Kodera |

THE LEGENDARY Doolittle Raid was named after its

commander and famous race pilot Jimmy Doolittle, but was conceived

by Navy Capts. Francis Low and Donald Duncan. The B-25B had no tail guns, but to ward off stern attacks

by Japanese fighters two broomsticks were mounted in the clear

tail blister. All 16 Mitchell's took off from the Hornet without mishap. The targets hit included industries and shipyards in and around Tokyo. The Japanese, who seemed to have received no warning, put up little resistance. Many of the bombers crash landed near the coast of China, some ditching into the sea. One made it to Vladivostok in the Soviet Union, the only Mitchell to land in one piece. Eight fliers were captured by the Japanese in China, and four died in prison camps. After the raid was revealed to the public, reporters asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt where the bombers were based. He answered, N.Shangri-La the fictitious utopian city in James Hilton's popular novel "Lost Horizon." The damage caused by the raid was insignificant, but it was damage to Tokyo, the enemy's capital. Coming only a few months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, it boosted morale among American fighting forces and the folks back home. The raid also showed the Japanese that they too could fall victim to a surprise attack. Like the Germans, the Japanese had convinced their citizens that their homeland was invulnerable. But the Doolittle raid was a portent of the massive bombing campaign that would end the war three years later. |

|

Sixteen B-25Bs crowd the Hornet's Flight Deck as the carrier steams toward it's launch point. |

|

Crew #1 after it's crash landing in China.

(from left) Staff Sgt Fred Baemer (bombardier). Staff Sgt Paul

Leonard (engineer-gunner), Lt Richard Cole (co-pilot), Lt Col

James Doolittle (Pilot and group leader), and Lt Henry Potter,

Navigator). |

|

| Doolittle leads the the specially trained flight off the Hornet's flight deck and on to Tokyo and other Japanese targets. Painting by W. Phillips. |

|

| On a flight deck full of North American B-25B Mitchell medium bombers, recently promoted Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle and the captain of the aircraft carrier Hornet confer before launching a daring raid on Japan, in Shaw's "The Hornet's Nest". Painting by W. Phillips |

Doolittle Raiders

The surprise Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was only the beginning of bad news from the Pacific. In the ensuing weeks, Wake Island, Singapore, Hong Kong and most of the Philippines were overrun by the Japanese army.

Within an incredibly short time, the Japanese had invaded and conquered huge land areas on a front that extended from Burma to Polynesia. By April 1, 1942, Bataan had fallen, and 3,500 Americans and Filipinos were making a brave last stand on the tiny island of Corregidor. There seemed to be no end to the Japanese aggression. Never before had America's future looked so grim.

Soon after the death toll at Pearl Harbor had been totaled, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked America's top military leaders, Army Generals George C. Marshall and Henry H. "Hap" Arnold and Admiral Ernest J. King, to figure out a way to strike back at Japan's homeland as quickly as possible. Although there was nothing they wanted to do more, it seemed an impossible request to carry out.

In response to the president's persistent urging, Captain Francis S. Low, a submariner on Admiral King's staff, approached King and asked cautiously if it might be possible for Army medium bombers to take off from a Navy carrier. If so, could they be launched against Japan?

The question was passed to Captain Donald B. "Wu" Duncan, King's air operations officer. After studying the capabilities of several Army Air Forces (MF) medium bombers, Duncan concluded that the North American B-25 might be capable of taking off from a carrier deck. He recommended takeoff tests be conducted before any definite plans were made.

When this basic idea was passed to General Arnold he called in Lt. Col. James H. "Jimmy" Doolittle, a noted racing and stunt pilot who had returned to active duty in 1940 and was now assigned to Amold's Washington staff. He asked Doolittle to recommend an MF bomber that could take off in 500 feet from a space not more than 75 feet wide with a 2,000 pound bomb load and fly 2,000 miles. Arnold did not say WHY he wanted the information.

Doolittle checked the manufacturers' data on the AAF's medium Bombers-the Douglas B-18 and B-23, North American's B-25 and -Martin B-26. He concluded that the B-25, if modified with fuel tanks, could fulfill the requirements. The B-18 could not carry enough fuel and bombs, the wingspan of the B-23 was too large and the B-26 needed too much takeoff distance.

The plan called for a Navy task force to take 15 B-25s to a point about 450 miles off Japan. There, they would be launched from a carrier to attack military targets at low altitude in five major Japanese cities. including Tokyo, the capital. The planes would then fly on to China, where the planes and the crews would be absorbed into the Tenth Air Force, then being organized to fight in China Burma-India (CBI) theater.

On February 2, 1942, two B-25s were hoisted aboard USS Homet, the US's newest carrier, at Norfolk, Va. A few miles off the Virginia coast, the lightly loaded bombers were fired up and took off without difficulty. Hornet was then ordered to proceed to the West for its first war assignment.

Jimmy Doolittle, a very energetic man, decided that the B-25 crews would consist of five men: pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier and engineer-gunner. Twenty-four B-25s and their crews would be assigned to the mission from the three squadrons of the 10th Bomb Group and its associated 89th Reconnaissance located at Pendleton, Ore. To preserve secrecy, Doolittle personally began making all the arrangements for the training equipment without revealing why he wanted things done.

The four squadrons were ordered to Columbia, S.C. En route, designated planes were modified with extra fuel tanks and assorted plumbing at Minneapolis, Minn. New incendiary bomb shackles were ordered, along with electrically operated motion-picture cameras that would be activated when the bombs were released. Intelligence information, maps and target folders for the five major Japanese cities were prepared.

When the four squadrons arrived at Columbia, the word was passed that volunteers were needed for "a dangerous mission." Almost every man in the four squadrons volunteered; the squadron commanders chose 24 crews, plus extra armament specialists and mechanics to ready the aircraft. The selected men and the planes were sent to Eglin Field, Fla., beginning in the last week of February.

Doolittle arrived at Eglin on March 3 and assembled the entire group of 140 men. "My name's Doolittle," he said. "I've been put" in charge of the project you men have volunteered for. Its a tough one, and it will be the most dangerous thing any of you have ever done. Anyone can drop out and nothing will ever be said about it.

Doolittle paused and the room was quiet. Several hands went up and a lieutenant asked if Doolittle could give them any more formation. "Sorry, I can't right now. " he said. "I'm sure you'll start getting some ideas about it when we get down to business-that brings up the most important point I want to make- and you're going to hear this over and over again. This entire mission must be kept top-secret. I not only don't want you to tell your wives or buddies about it, I don't even want you to discuss it among yourselves.."

From the first day of training, it was understood that all the volunteer crews would participate in the training; however. only 15 planes would eventually go on the mission. This was done to ensure that there would be plenty of spare crews on hand to replace anyone who became ill or decided to drop out.

As the takeoff training of the pilots progressed, it proved to be harrowing experience for most of them. Army Air Force pilots were not taught during their training to take off over extremely short distances at bare minimum airspeed. Taking off in a medium bomber with the tail skid occasionally striking the ground was unnatural and scary to them. But under U.S. Navy Lieutenant Henry J. Miller's patient instruction, they all soon learned the required skills.

In addition to takeoff practice, it was hoped that each crew would receive 50 hours of flying time to be divided into day and night navigation, gunnery, bombing and formation flying. But maintenance problems kept the planes on the ground most of the time.

Every B-25 model at that time was equipped with one upper and one lower turret, each with twin .50-caliber machine guns. But the upper and lower turret mechanisms continually malfunctioned; the lower turret was especially difficult to operate. Doolittle ordered the lower turrets removed and additional gas tanks installed in their place.

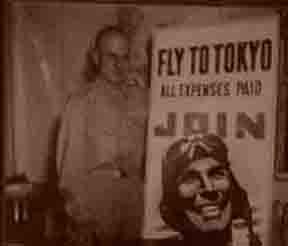

|

This is Jimmy Doolittle about two months before the raid. Thanks

Doc! |

There was a single .30-caliber movable machine gun in the B-25's nose, which was placed in a gun port by the bombardier when needed. There were no guns in the tail, so Captain C. Ross Greening, the armament officer, suggested that two broomsticks be painted black and installed there to deceive enemy fighters. Since the bombing was to be at 1,500 feet or less, Greening also designed a simple bombsight he called "Mark Twain" to replace the top-secret Norden bombsight. It was made from two pieces of aluminum that cost about 20 cents.

One of the volunteer gunners had other duties. When 1st Lt Robert "Doc" White, a physician attached to the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron, heard of the call for volunteers, he asked to be included. He was told there was no room for a passenger; The only way he could go was as a gunner. White said that was all right him. He took gunnery training, qualified with the second highest score with the twin .50s on the ground targets, and was assigned to a crew. His presence on the mission would prove to be fortuitous..

Meanwhile, Captain Wu Duncan had arrived in Honolulu and conferred with Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of the Pacific Fleet, and conveyed the plan for an attack from to transport the Army bombers to the launch point. Nimitz liked the idea and gave the task of carrying it out to Admiral "Bull" Halsey, who was anxious to tangle with the enemy in any way he could.

Duncan worked with the CINCPAC (commander in chief Pacific) planning staff on the details for a 16-ship task force. It was decided that seven ships would accompany the Homet from the Alameda Naval Air Station near San Francisco and rendezvous with an eight ship force that included Halsey's flagship, the carrier Enterprise. The linkup would take place near the 180th meridian.

By the middle of March, Homet, now destined to be the ship that would deliver the B-25s to the takeoff point, had passed through the Panama Canal and proceeded to Alameda. At the end of the third week in March, Captain Duncan wired Washington from Honolulu: "Tell Jimmy to get on his horse."

This coded message was all Doolittle needed to get his men

and planes moving to the West Coast. Since two of the B-25s had

been damaged in training, the 22 remaining were flown to McClellan

Field, in Sacramento, Calif., for final inspections before proceeding

to Alameda. All of these crews would go aboard the carrier.

Captain Duncan flew to San Diego to confer with Captain Marc

A. Mitscher, skipper of Homet. Mitscher had not been told about

the mission until then and was delighted to have a part in it.

Since he had watched the first two B-25s take off successfully

several weeks earlier, he was confident it could be done. Duncan

then went to San Francisco to await the arrival of Doolittle from

Florida, Halsey from Hawaii and Homet from San Diego.

The three men, joined by Captain Miles Browning, Halsey's chief of staff, met informally in downtown San Francisco to discuss the details and determine if anything had been left undone. The plan was for Hornet, in company with the cruisers Nashville and Vincennes, the oiler Cimarron, and the destroyers Gwin, Meredith, Monssen and Grayson-to be known as Task Force 16.2-to leave San Francisco April 2. Halsey, aboard Enterprise, was in charge of Task Force 16.1 and would leave Hawaii on April 7, accompanied by the cruisers Northampton and Salt Lake City, the oiler Sabine, and destroyers Balch, Benham, Ellet and Fanning.

The rendezvous of the two forces would become Task Force 16 and would take place on Sunday, April 12, at approximately 38 degrees O minutes north latitude and 180 degrees 0 minutes west longitude. The force would then proceed westward and refuel about 800 miles off the coast of Japan. Then the oilers would detach themselves while the rest of the task force dashed to the launch point.

Halsey later reported in his memoirs, "Our talk boiled

down to this: we would carry Jimmy within 400 miles of Tokyo,

if we could sneak in that close; but if we were discovered sooner.

we'll have to launch him anyway, provided he was in reach

of either Tokyo or Midway."

What Halsey did not discuss was the tremendous risk the Navy

was taking. If marauding Japanese submarines discovered the task

force steaming westward, it would be an excellent opportunity

to cripple what was left of the Navy's strength in the Pacific

Doolittle knew full well that if Halsey's ships were under heavy

attack, the B-25s stored topside would be pushed over the side

to make the flight deck available so Homet's fighters could be

back on deck to help protect the task force.

When the B-25s landed at Alameda on April 1, Doolittle and Captain Ski York greeted each crew. "Anything wrong with your plane?" they asked. If a pilot admitted some malfunction, he was directed to a nearby parking ramp instead of the wharf.

Originally, only 15 planes were to be loaded, but Doolittle asked for one more to be hoisted aboard. When the carrier was at sea, it would take off and return to the mainland to show the other B-25 that takeoffs were not only possible but could be made easily. Although the bomber crews had been told that B-25s had made successful takeoffs previously, none had ever seen it done, nor had they done it themselves. Lieutenant Miller, the Navy pilot who had instructed them in carrier takeoffs, would be aboard that B-25.

The next morning, Task Force 16.2 prepared to depart from San Francisco Bay. Just before Hornet was to depart, Doolittle was ordered ashore to receive an urgent phone call from Washington. He recalled: "I thought it was going to be either General Hap Arnold or General George Marshall telling me I couldn't go. My heart sank because I wanted to go on that mission more than anything....

It was General Marshall. 'Doolittle?' he said. 'I just called

to wish you the best of luck. Our thoughts and our prayers will

be with you. Goodbye, good luck, and come home safely." All

I could think of to say was, 'Thank you, Sir, thank you.' I returned

to the Hornet feeling much better. "

Shortly before noon, Hornet passed under Golden Gate Bridge.

That afternoon, Mitscher decided to tell his men where they were

going. He signaled to the other ships, "This force is bound

for Tokyo ~ As he recalled later, when he made the announcement

"Cheers from every section of the ship greeted the announcement,

and morale reached a new high, there to remain until after the

attack was launched and the ship was well clear of combat areas."

The next day, April 3, Doolittle changed his mind about sending

the 16th plane back to the mainland. A Navy blimp, the L-8, arrived

overhead with spare parts for the B-25s. Air-patrol coverage was

provided as far as possible by a Consolidated PBY Catalina.

Doolittle assembled his crews and introduced Commander Soucek

and Lt. Cmdr. Stephen Jurika. Soucek was the ship's officer, and

he described the basics of carrier operations. Jurika, Homet's

intelligence officer, briefed them on the target cities am surrounding

areas.

Jurika had been an assistant naval attache in Japan in 1939

and had obtained much valuable information about Japanese industry

and military installations. He spoke to the crews almost every

day, telling them about Japanese customs, political ideologies

and history. Doolittle allowed the pilots to choose their targets

in the assigned cities. Lieutenant Frank Akers, the carrier's

navigator. gave the pilots a refresher course on navigation. Doc

White, the physician-gunner on Lieutenant Don Smith's crew, gave

talks about sanitation and first aid.

Jurika had been an assistant naval attache in Japan in 1939

and had obtained much valuable information about Japanese industry

and military installations. He spoke to the crews almost every

day, telling them about Japanese customs, political ideologies

and history. Doolittle allowed the pilots to choose their targets

in the assigned cities. Lieutenant Frank Akers, the carrier's

navigator. gave the pilots a refresher course on navigation. Doc

White, the physician-gunner on Lieutenant Don Smith's crew, gave

talks about sanitation and first aid.

Doolittle made it a practice to meet with the crews two or

three times a day. He continually warned them not to bomb the

Imperial Palace and to avoid hospitals, schools and other nonmilitary

targets. He said that most planes would carry three 500-pound

demolition bombs and one 500-pound incendiary. He planned to take

off in the late afternoon with four incendiaries and drop them

on Tokyo in darkness. The resulting fires would light up the sits

and serve as a beacon for those following and guide them to their

respective targets in Tokyo, Yokohama, Kobe, Nagow Osaka. All

aircraft would then proceed to China and be guided by homing beacons

to landing fields where they would refuel before proceeding to

Chungking, the ultimate destination.

Mitscher and Halsey joined forces as planned. Meanwhile arrangements

in China were not going well. Japanese ground were moving in strength

toward the airfields where the B-25s were to refuel. Although

the Americans and Chinese in ChungKing told that they could expect

some aircraft to arrive and to prepare for them by placing fuel

and setting up homing beacons. They not told that the planes would

be arriving from the east after bombing Japan. Misunderstandings

developed and were compounded when Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek

asked that the arrival of the planes be delayed so he could move

his ground forces into position to prevent occupation of the Chuchow

area where one of the refueling airfields was located.

As the task force continued westward, the Japanese knew from intercepted radio messages as early as April 10 that an an enemy carrier force was steaming toward them. However, it was estimated that it would have to approach to within 300 miles of their coast in order to launch any carrier planes. If that was where the task force was headed, there would be plenty of time to intercept it.

Unknown to the Americans, a line of radio-equipped picket ships was positioned about 650 miles off Japan, and they could signal the approach of any large force and warn the land-based air defense forces to prepare for an attack.

Meanwhile, a Japanese navy air flotilla was alerted to back up homeland air defenses. Patrol bombers would be dispatched when the enemy force was estimated to be about 600 miles out. However, when the American task force observed radio silence for the last 1,000 miles, the Japanese cautiously decided that it might be headed elsewhere.

In the early morning hours of April 18, Enterprise's radar

spotted two small ships. The force changed course briefly to avoid

them. The weather turned sour, light rain was falling, and green

water was plunging down Homet's deck. A dawn patrol was sent up

from Enterprise to scout the area. One of the pilots sighted an

enemy surface ship and dropped a message to the "Big E's"

deck, noting the ship's position and adding, "Believed seen

by enemy."

Admiral Halsey promptly flashed a message to Captain Mitscher:

"Launch planes to Colonel Doolittle and gallant command luck

and God bless you."

The B-25s were quickly loaded and one by one moved into takeoff

position. Doolittle was first off at 0820 hours; the 16th was

off an hour later. Just as the pilot of the last plane had started

his engines, a deckhand slipped on the wet deck and fell into

B-25's whirling left propeller, which severed his arm.

One by one, the B-25s droned on toward Japan. None flew close

formation with another, and only a few actually saw other B-25s

as they proceeded toward their respective targets.

Shortly after noon, Tokyo time, Doolittle called for bomb doors open, and Sergeant Fred Braemer sighted down the 20-cent bomb sight and triggered off four incendiaries into the capital city's factory area. Fourteen other crews found their respective targets however, one B-25, with its top turret inoperative and under attack by fighters, dropped its bombs in Tokyo Bay. Several others were also attacked, but none suffered any noticeable damage.

All of the planes except one turned southward off the east coast of Japan and then westward toward China. Captain York had a difficult decision to make. Both of his B-25's engines had burned excessive amounts of fuel on the way to Japan, and he knew he and his crew would have to ditch in the shark-infested China Sea if they followed the planned route to China. He elected to proceed against orders to Soviet territory and landed near Vladivostok. He had hoped he could persuade the Soviets to refuel the plane and allow them to continue to China, but the aircraft and crew were promptly interned because the Soviet Union wanted to retain its neutral status with Japan. The crew finally escaped into Iran 14 months later.

As the other aircraft turned toward China, they experienced head winds, and it appeared that few, if any, would reach the coast before running out of fuel. Although the head winds then fortuitously turned into tail winds, the weather worsened in the late afternoon as they were approaching the coastline. Doolittle and 11 other pilots elected to climb into the clouds and proceed inland on instruments. When their fuel reached the zero mark, the crews bailed out. One crew member was killed attempting to depart the airplane. All others made it with only bruises, slight cuts or sprained ankles and slowly made their way to Chuchow and Chungking with the help of Chinese peasants. More than a quarter-million Chinese subsequently paid with their lives when ruthless Japanese soldiers murdered anyone suspected of helping the Americans and even people whose villages the Americans had passed through.

Four pilots elected to crash-land or ditch their aircraft. Two crewmen drowned while trying to swim to shore. Four members of one crew were seriously injured; they were assisted by the rear gunner, corporal David Thatcher, and friendly Chinese to a hospital run by missionaries and were joined there by Lieutenant White and his crew. It was there that "Doc" White amputated the leg of the pilot Lieutenant Ted W. Lawson, and gave two pints of his own blood to save Lawson's life. Lawson later wrote about his experiences in Thirty Seconds over Tokyo. Thatcher and White later rewarded the Silver Star for their gallantry.

Sixty four of Doolittle's "Raiders" eventually arrived in Chungking.. some were retained in the theater to serve in the Tenth Air Force; others were returned to the States and assigned to other units. Three pilots and one navigator later became prisoners of the Germans.

Eight crewmen were captured by the Japanese, tortured, given mock court-martial and sentenced to die. Three of them were executed by firing squad; one died of malnutrition. The remaining four-George Barr, Jacob DeShazer, Robert L. Hite and Chase L Nielson-survived 40 months of captivity, most of it in solitary confinement, and returned to the States after the war.

The question has been asked: Can this raid be considered successful if all aircraft were lost and relatively little damage was done to the targets?

The answer is a strong affirmative. The mission provided the first good news of the war and was a tremendous morale booster for America and her allies. Japanese morale, on the other hand shattered because their leaders had promised that their homeland could never be attacked.

The original purpose of the raid, as stated by Doolittle before he departed, was to prove that "Japan was vulnerable and that a surprise air raid would create confusion, impede production and air defense forces to be withdrawn from the war zones to the home islands against further attacks." All of that occurred.

Besides being the first offensive air action against the Japanese home islands, the Doolittle-led raid accomplished some other historic firsts. It was the first combat mission in which the US Air Forces and the U.S. Navy teamed up in a full-scale operation against the enemy. Jimmy Doolittle and his raiders were the first to fly land-based bombers from a carrier deck on a combat mission and first to use new cruise control techniques in attacking a distant target. The incendiary bombs they carried were forerunners of those used later in the war. The special cameras specified by Doolittle to record the bomb hits was later adopted by the AAF. The after-action crew recommendations armament, tactics and survival equipment were used as a basis for other improvements.

Jimmy Doolittle's famous air raid against Japan marked the beginning of the turnaround toward victory for America and her allies in World War II.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Specifications and Technical Data...

|

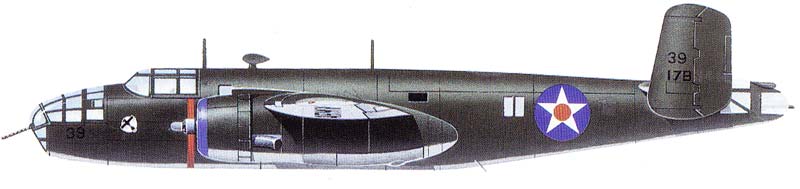

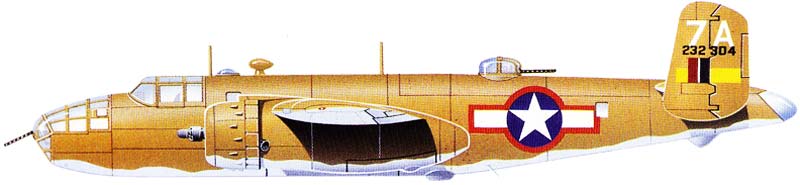

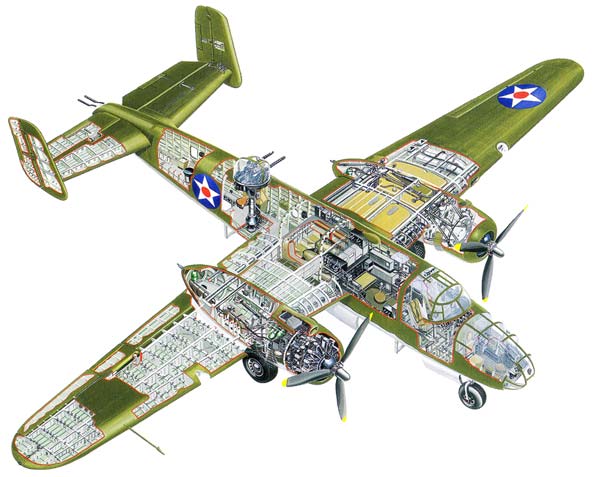

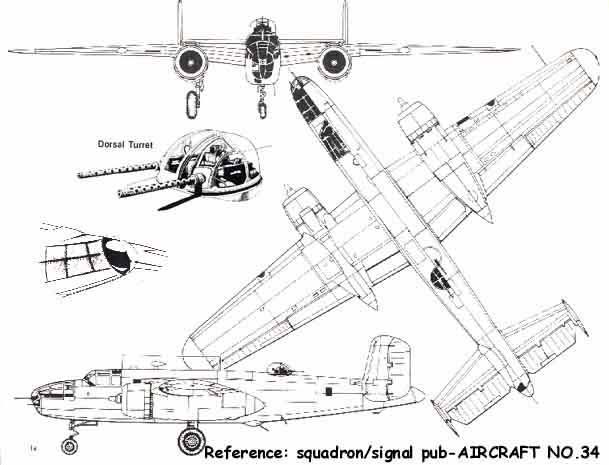

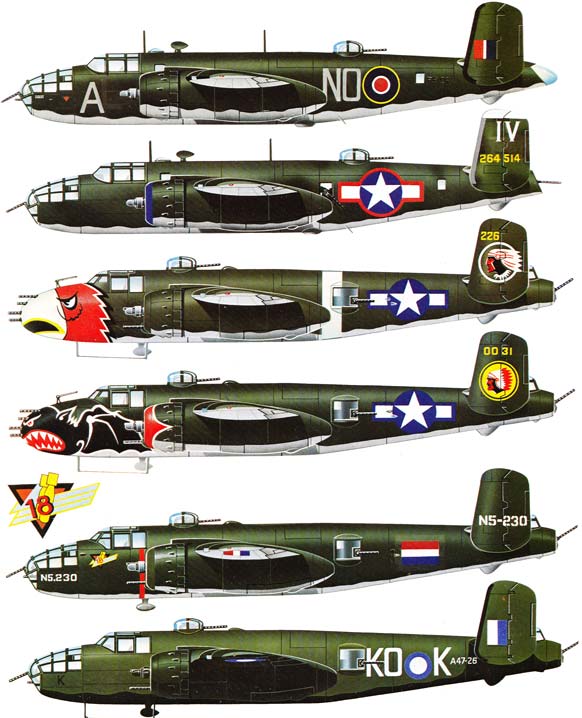

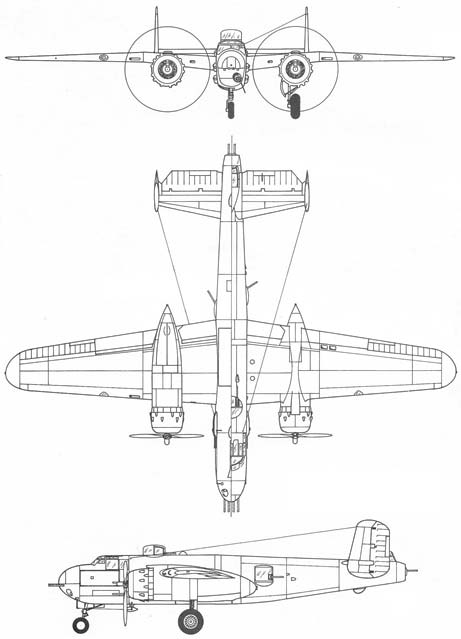

Type: medium bomber and attack with crew from four to six Engines: (B-25, A. B), two 1,700 hp Wright R-2600-9 Double Cyclone 1 4-cylinder two-row radials: (C, D, G) two 1,700 hp R-2600 13: (H, J. F-10), two 1,850 hp (emergency rating) R-2600-29 Dimensions: Performance: maximum speed (A) 315 mph: (B) 300 mph: (C, G)

284 mph: (H. J) 275 mph: initial climb

(A, typical) 1,500 ft/ min: (late models. typical) 1,100

ft /min: service ceiling (A) 27,000 ft: (late

models. typical) 24,000 ft: range (all, typical) 1,500

miles. History: first flight (NA 40 prototype) January 1939: (NA 62, the first production B 25) 19 August 1940: (B 25G) August 1942 Named in honor of the fearless US Army Air Corps officer who was court-martialled in 1924 for his tiresome (to officialdom) belief in air power, the B-25 was designed by a company with no previous experience of twins, of bombers or of high performance warplanes was made in larger quantities than any other American twin engine combat aircraft and has often been described as the best aircraft in its class in World War II Led by Lee Atwood and Ray Rice, the design team first created the Twin Wasp-powered NA40, but had to start again and build a sleeker and more powerful machine to meet revised Army specifications demanding twice the bomb load (2,400 lb). The Army ordered 184 off the drawing board, the first 24 being B-25s and the rest B 25A with armour and self-sealing tanks The defensive armament was a 0 5 in manually aimed in the cramped tail and single 0 3 in manually aimed from waist windows and the nose: bomb load was 3,000 lb. The B had twin 0-5 in in an electrically driven dorsal turret and a retractable ventral turret, the tail gun being removed On 18 April 1942 16 B-25Bs led by Lt-Col Jimmy Doolittle made the daring and morale-raising raid on Tokyo, having made free take-offs at gross weight from the carrier Hornet 800 miles distant. Extra fuel. external bomb racks and other additions led to the C, supplied to the RAF, China and Soviet Union. and as PBJ 1 C to the US Navy The D was similar but at the new plant at Kansas City In 1942 came the G, with solid nose fitted with a 75 mm M-4 gun, loaded manually with 21 rounds. At first two 0 5 in were also fixed in the nose, for flak suppression and sighting, but in July 1943 tests against Japanese ships showed that more was needed and the answer was four 0 5 in ''package guns'' on the sides of the nose Next came the B 25H with the fearsome armament of a 75 mm, 14 0 5 in guns (eight firing ahead, two in waist bulges and four in dorsal and tail turrets) and a 2,000 lb torpedo or 3,200 lb of bombs. Biggest production of all was of the J, with glazed nose, normal bomb load of 4,000 lb and 13 .05 in guns supplied with 5,000 rounds The corresponding attack version had a solid nose with five additional .05 in guns Total J output was 4,318, and the last delivery in August 1945 brought total output to 9,816. The F 10 was an unarmed multi-camera reconnaissance version, and the CB-25 was a post war transport model The wartime AT 24 trainers were redesignated TB 25 and, after 1947, supplemented by more than 900 bombers rebuilt as the TB 25J, K, L and M Many ended their days as research hacks or target tugs and one carried the cameras for the early Cinerama |

|

|

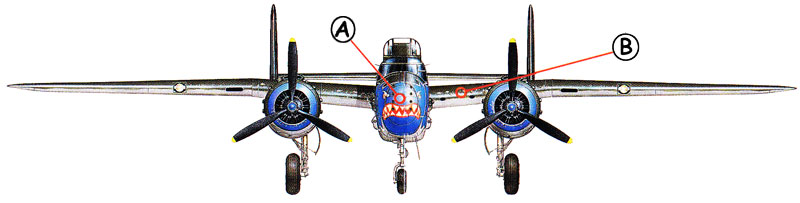

| A: With a hard-hitting 75-mm cannon in nose, the B-25H was one of the most heavily armed aircraft of the war (Pictured is the B-25J). | B: All but the first few Mitchells had this characteristic "inverted gull" wing. This modification made the B-25 much more maneuverable than when it had a standard straight wing. |

|

||

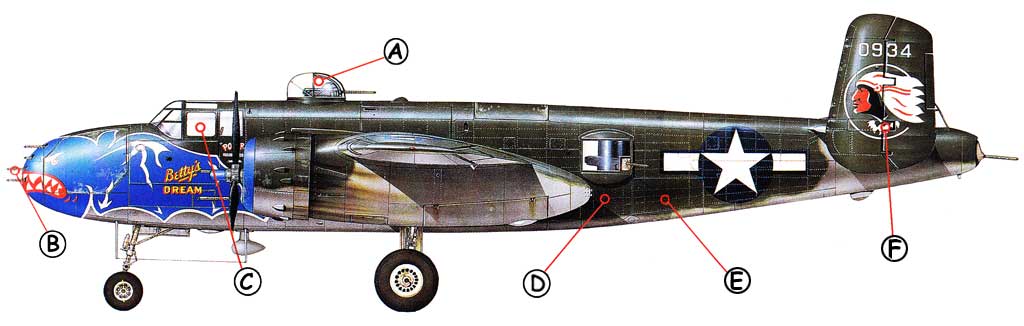

| A: The dorsal turret was used as protection against fighters, but it could be locked forward to add extra weight to the nose guns. | B: The B-25J had a fearsome armament of 12 heavy machine guns in the nose and on the sides of the fuselage. | C: Solid-nosed Mitchells generally flew with a crew of five. Pilot, copilot and gunner occupied the flight deck, while two more gunners manned the waist and tail guns. |

| D: Quite apart from the heavy gun armament, the B-25 could also lift 3,000 pounds of bombs in its two vertical bomb bays. | E: The crew boarded the aircraft through hatches in the lower fuselage. | F: By far the most colorful of all the wartime Mitchells were those assigned to the 345th Bomb Group (Medium), which flew this solid-nose B-25J in the Far East. The Group was known as the "Air Apaches," and carried a large Indian's head on the tail. |