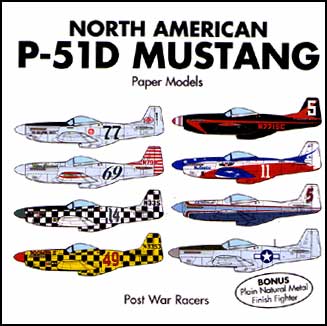

The North American P-51 Racers

Racing In Reno

Over the mountains of western Nevada, Laird Doctor bounces through the afternoon thermals in the front seat of his AT-6 World War II trainer. Easing out of a shallow left turn, he keeps a watchful eye on the six T-6s strung off his right wing. Doctor issues a stream of minor adjustments over the radio to nudge them into position: "Number five, you're too low, ease it up. Race 22, slow it down, slow it down.

Fifty-six, tighten it up on the end, tighten it up." The stolid trainers lumber into line like so many fat, obedient geese. "Okay, gentlemen, we're over the ridge at 200 feet. Line abreast, line abreast. Final power increase coming on. . . now!" Doctor toggles a switch marked "smoke" and a thick white plume billows from the exhaust stack. Once satisfied that everyone is lined up on the steady dive toward the airport, he pulls up sharply and opens the starting gate with the ritual words "Gentlemen, you have a race."

From their vantage at the first turn, the pylon judges watch

the line of distant dots bunch up, then disappear below the horizon as the pilots

dive for starting speed. Soon an unearthly growl rolls across the desert from

the west. The gaggle of T-6s, much closer now, looms up out of the shimmering

heat of the desert floor and thunders toward the first pylon.

From their vantage at the first turn, the pylon judges watch

the line of distant dots bunch up, then disappear below the horizon as the pilots

dive for starting speed. Soon an unearthly growl rolls across the desert from

the west. The gaggle of T-6s, much closer now, looms up out of the shimmering

heat of the desert floor and thunders toward the first pylon.

As the T-6s near the number-one pylon, the blob bunches up

again as they all seek the tightest course around the corner. The trainers hurtle

past the pylon at 50 feet, flying a tight but fluid formation turn at over 250

mph. The crackle of supersonic shocks generated by the propeller tips rings

in the ears. John Carstarphen and the three members of his judging team cluster

at the base of the pylon, peering intently upward to make certain none of the

aircraft cut in side the phone pole, and note the order of passing.

The National Championship Air Races at Reno are a magnificent

anachronism in American aviation. It is a ritual of risky business from the

wild youth of aviation preserved beyond its time. The three-ring circus is part

demolition derby, part technology evaluation lab, and part aviation history

museum. More than anything else, Reno is a celebration of the piston engine.

And like monster truck jumping and mud wrestling, it is a uniquely American

spectacle.

During their prime, in the 1930s, the Cleveland National

Air Races were as much a part of the national sporting consciousness as the

Indianapolis 500 is today.

But that changed after World War II forced dramatic

changes in aviation technology, pushing the piston engine to its limit, then

replacing it with the turbojet. For a few years after the war there were attempts

to race the big piston fighters on small pre-war courses, but the results were

disastrous. The Thompson Trophy race at Cleveland in 1949 was the last straw.

During the second lap, a highly modified P-51 dove into a house, killing a housewife,

her one-year-old child, and the pilot. Midget racers competed at various sites

through 1960, but the big classics disappeared until 1964, when a Nevada rancher

and hydroplane racer named Bill Stead organized the first modern air race at

the Sky Ranch airfield outside Reno. Two years later the races moved to the

old air base named for Stead's brother, where they have grown and prospered.

Now 150,000 people show up each year to revel in the last big-time closed-course

pylon air races.

Of the four race classes at Reno -- Biplanes, Formula Ones,

AT-6s, and Unlimited's -- the last category is the biggest draw. The Formula

Ones and biplanes are slick homebuilder constructed around small general aviation

engines, and the AT-6 trainers are all alike save paint scheme and speed mods.

But the Unlimited's are just what the name says. Aside from a rule stating that

they must be propeller-driven and powered by piston engines, there are no holds

barred. Two weeks of time trials and preliminaries culminate in the Unlimited

Gold race on Sunday.

The Gold race comes last, it is the fastest, and it offers

the largest purse.

Compared with the genteel and efficient personal transport

that is offered by promoters of general aviation, what goes on at Reno is definitely

fringe activity. But hang around for a while and you get the sense that this

is what flying is all about. This is flying in the raw, for the sheer exhilarating

hell of it, with all the rewards and risks out on the table and not hiding under

a veneer of respectability.

Reno is an event on the edge in more ways than one. Each

year race organizers set aside part of the receipts to purchase a little more

of the land under the race course, hoping eventually to buy it all before someone

builds a subdivision and shuts them down. The Unlimiteds--some chopped and channeled

and sporting monster engines, some looking as if they just flew in from active

duty - are themselves an endangered species. And there is constant friction

between the racers and the organizers over the prize money. "If you qualify

fastest, win your heat races, and win the Gold, you might take home $40,000

or $50,000," says two-time winner Steve Hinton. "The Merlin [engine] in Strega

alone would cost you twice that amount."

There is talk among the racers of a boycott. But missing the annual gathering would be counterproductive at best. Any discord in the ranks may scare off what meager sponsorship money is available. As much as Reno needs the racers, the racers need Reno. No other venue has managed this much dependable racing, and until some place does, there's no place else to go.

As captain of the number-one pylon, John Carstarphen, calmly

resplendent in his black and white striped referee's shirt, has a hammerlock

on what he describes as the best seat in the house. The picture of judicial

impartiality, he was pressed into service 15 years ago, back when there weren't

enough pylon judges to go around. It seemed like a thankless task. The few volunteers

spent the time between races bouncing across the desert from one course to another.

Now that interest in the races has escalated, there is a waiting list 30 deep

for Carstarphen's job.

The herd of T-6s thunders down the back of the course like

stampeding elephants, again disappearing into the desert floor, as the race

degenerates into a treacherous parade of hurtling metal and sonic assault. 'We

could call in the results now and save these guys the gas," Carstarphen notes

with a wry grin. It seldom fails, he says, that the first order in which they

pass the first pylon is the order in which they finish at the home pylon. Ten

minutes and five laps later, Carstarphen's prediction is vindicated. The order

of finish is identical to the order of the first lap.

Reno is aviation's last bastion of organized recklessness.

Here a pilot can literally take his life into his own hands and as close to

the desert floor as he or she dares. For the AT-6 racers, low flying seems a

point of honor. The racers explain their daring as an attempt to gain competitive

advantage rather than an expression of machismo. The lower you fly, they claim,

the easier it is to maintain the tightest course around the 40foot pylons. Flying

the tightest course will force your competitors outside or above you, requiring

them to expend more energy to pass you.

Reno is aviation's last bastion of organized recklessness.

Here a pilot can literally take his life into his own hands and as close to

the desert floor as he or she dares. For the AT-6 racers, low flying seems a

point of honor. The racers explain their daring as an attempt to gain competitive

advantage rather than an expression of machismo. The lower you fly, they claim,

the easier it is to maintain the tightest course around the 40foot pylons. Flying

the tightest course will force your competitors outside or above you, requiring

them to expend more energy to pass you.

And since the T-6 class is the equivalent of stock car racing - everyone starts with the same basic airframe and a 600 horsepower radial engine - winning usually boils down to who gets first to the number-one pylon at pylon level in the tightest position. But as Unlimited racer Rick Brickert observes, "There is no way to set a new record for low flying. The best you can hope for is a tie for first place." This year Jim Mott ties the standing record, flying his T-6 into the ground in a frantic attempt to qualify. The airplane is demolished, but Mott walks away, hoping to race again next year.

Unlimited-class air racing is slowly dying. Every year a

few more great old fighters are missing, a few more familiar faces are gone.

This year several Hawker Sea Furies and two P-51 Mustangs are out of the running,

as is a Chance-Vought Corsair, whose pilot ended up in a tree after bailing

out at the last minute. Out on the pylons, talk is of what will happen on the

Day They Break the Last Merlin, the legendary Rolls-Royce engine that powered

the Spitfire and the Mustang. Ironically, in the very act of preserving the

essence of the kind of aviation that the Merlin represents, the racers are helping

to condemn it to extinction.

A lone Curtiss P-40N sits in the center of the Unlimited

pit, a pickpocket in league with bank robbers. With generic olive drab and gray

paint and star and bar, it is literally a museum piece, one of the few remaining

specimens of the thousands of Warhawk's that flew in World War II. Once a year

the owners take it out of the Warhawk Air Museum in Caldwell, Idaho, bring it

to Reno, and run it in the Bronze race. They lose, of course, and when the air show

season is over they put it back in the museum alongside an older, rarer P-40E

and a P-51B. Perhaps only two dozen P-40s can still fly, but curator Sue Paul

thinks the rewards of showing the audience a vintage U.S. fighter are worth

the risk.

The fate of the sport is uncertain. A new source of Unlimited's

is needed, for one thing. The old Lear 23 corporate jets are close to the end

of their service lives, and some will eventually be scavenged for parts. Perhaps

you could build an experimental class around the high-speed wings, add a new

fuselage and a piston engine. One loosely formed concept calls for racing older

corporate-class turboprops, like the Mitsubishi MU-2, as a class. You'd still

have racing, but most agree that without the old big-bore piston engines and

the classic forms they propel, you wouldn't have much. Says Bill Rheinschild,

who is flying his P-51 this year, "If we quit racing Mustangs and Bearcats,

we'll quit racing."

Carstarphen's claim to the best seat in the house is arguable.

To understand Reno, you have to hang out with the rowdies in Section Three of

the grandstand. You need to walk out of the pits, with their intimate array

of racers and crew, past the ritzy Checkered Flag Club, where members in monogrammed

jackets munch on hors d'oeuvres, past the reserved seats, the exclusive press

and VIP tents. Walk past the box seats to the general admission grandstand.

There you will find the noisy, raucous, thrill-crazed essence of Reno: a vibrant

orange blur in Section Three.

It began in 1984, when repeat visitors started recognizing

one another. Section Three soon evolved into a full fledged fraternity. They

even have a scrapbook. Now the orange T-shirts and scorecards that are brandished

for every act, every race, and innocent passersby are a part of the show, along

with a cacophony of air horns and bull horns. "Ain't that some kind of flying?"

the announcer asks. "Oh, yeaaahhh!" comes Section Three's reply.

The people in the orange T-shirts come from most walks of

life, from across the country; all they have in common is the annual pageant

at Section Three, general admission grandstand, National Championship Air Races.

Admission to this club requires only a love of hot flying and big engines and

a commitment to come to Reno every September. Elliott Cross sums up the draw:

"A lot of people know that they're going to do this every year, forever."

Section Three and the pilots have formed a mutual admiration

society. Most of the air show and race pilots make their way to the stands to

be mobbed by orange fans, whose T-shirts are covered with pilots' autographs.

The only performer who doesn't garner an appreciative burst of waving grade

cards is an insipid would-be comedian with a J-3 Cub, a dog, and some ducks.

This is not why you come to Reno. Section Three is chafing for some real action.

They soon get it. Late in the afternoon a Navy pilot works

out with his F-14, booming around the sky with those big engines in burner half

the time and the noise aimed at the grandstands as often as possible. After

landing, the Tomcat taxis past the main grandstand, pivots to point at the seats

in Section Three, and runs up the engines with the brakes locked, compressing

the nose gear strut to take a bow. Then the pilot holds up an orange T-shirt.

Section Three leaps to its feet in reply, a frenzy of waving grade cards and

blaring air horns. The moment is even better than a Sikorsky Skycrane dropping

a school bus on the airport's infield from a mile up.

But Section Three's all-time favorites are Lyle Shelton and

Rare Bear. Brute force is the hallmark of this Grumman F8F-2 Bearcat. "Short,

fat airplanes aren't supposed to go this fast," Shelton says. The soft-spoken

pilot does not fit the expected image--something along the lines of Hulk Hogan

driving a Monster Truck.

Shelton seems uncomfortable in the role of celebrity, but he is too nice to say so. Saturday evening, standing atop the tractor-trailer that is Rare Bear's mobile support facility, he explains his involvement with air racing. He was here - by coincidence - back when the Reno races started, and something grabbed him during that first race. Nearly 30 years later the five time winner is the odds-on favorite to win again tomorrow. So what's the point of the exercise?

"Well, to win," Shelton says. 'To win. In any sport or endeavor

you like to win, to do your best, beat the other guys fair and square." Shelton

could be the Gary Cooper of air racing, taciturn and forthright, a straight

shooter with the biggest gun in town. "I've heard that everybody ought to have

a little bit of danger in their lives," he says. "I don't know if it builds

character but maybe it keeps a little character. I think it does something for

the human psyche to get on the edge now and then, one way or the other."

The 3,350 cubic inches shoehorned under the Bearcat's cowling

generate enough horsepower, well over 4,000, to pull Shelton and Rare Bear right

up to the edge of the performance envelope. Last year the pair set a new race

record, 468 mph. "Shelton is up near the limit," says Bill Rheinschild. "That

wing was never meant to go that fast, not like a P-51. Someday it may come apart

on him."

The 3,350 cubic inches shoehorned under the Bearcat's cowling

generate enough horsepower, well over 4,000, to pull Shelton and Rare Bear right

up to the edge of the performance envelope. Last year the pair set a new race

record, 468 mph. "Shelton is up near the limit," says Bill Rheinschild. "That

wing was never meant to go that fast, not like a P-51. Someday it may come apart

on him."

If Shelton is the Road Runner, blasting a trail of dust across

the high desert floor, Bill 'Tiger" Destefani is the conniving Wile E. Coyote,

secretly assembling his Acme Rocket-Powered Roller Skates and brandishing his

certified Bear-proof capture net. But Destefani just can't catch the wicked

fast Bearcat A cotton farmer from Bakersfield, California, Destefani exudes

country cunning. Pulling up a 5 gallon drum as a seat, he warms to the task

of explaining his strategy. It is a tale of telemetry and tactics. His team

keeps him apprised of the race situation by a two-word code radioed once per

lap.

The engine is wound so tight, he says, that pulling the throttle back too quickly will destroy it. Bottom line? He's got the stuff to beat Shelton. "Let me tell you something," he says, leaning forward, eyes glistening. Referring to Shelton's one lap closed-course record, only hours old, he says, "Four seventy-seven? That's baby shit. Wait until tomorrow." The basis for Destefani's optimism is a red and white P-51 Mustang, Strega, Italian for "witch." A stuffed witch on a broomstick adorns the top of the tarp covering Strega's pit. The stage is set for tomorrow's shootout. Racers, pit crews, and spectators retire to party away the remaining hours.

Midnight. A walk along the deserted ramp. A gleam shifts

in the darkness, then reveals itself as the silver and blue P-51D Platinum Plus.

It's there and yet it's not. The Mustang has been hand polished with cornstarch

for hours until the finish is so fine it reflects the dark of the cosmos. You

can't actually see the whole airplane; its form is defined by curved reflections

of a thousand tiny pinpoints of starlight.

A resonant howl drifts down from further up the pit lanes.

An engine is running in the dead of night. Out on the ramp, something fantastic

stands alone. It's the Pond Racer, bathed in a pool of light from portable spots,

all flowing white curves and engine pods. The four stubby blades on the right

engine form a translucent disk. The crew stands transfixed. One holds a fire

extinguisher.

The group stares at what may be the future of air racing.

The exotic all-composite twin-boom design is yet another radical departure by

Burt Rutan, this one built to the specifications of millionaire airplane collector

Bob Pond. The highest point on the Pond won't reach a P-51 wingtip. The big

guys could run over it on a taxiway. If it can win the Unlimited, it will contribute

immeasurably to the preservation of aviation's piston-power heritage. The day

a modern design like this wins the Gold race, all the World War II contenders

will finally be recognizable for what they are: obsolete.

The newborn is still teething. The Pond Racer wails, straining

at the cord that binds the right tail boom to the ramp. Few spectators knew

that the airplane flew today's qualifying race with the right engine at idle.

The Rutan crew must find out why before morning. As the rpm slides up and down,

subtle changes in the sound of the distressed engine provide clues. Sometimes

it runs smoothly, sounding like a massive electric dynamo. At other times, a

sporadic chuttering undertone is accompanied by belches of blue flame from the

exhaust stacks. For the first time in the history of air racing, a malfunction

in the engine sounds like a software problem.

Test complete, data from the run stored in computer memory,

the crew shuts down the engine and attaches fans to the nacelle to flush out

the heat. Crew chief Bruce Evans isn't talking. Nor is anyone else. All discussion

of the Pond Racer must come from the front office. It is a tense and frustrated

crew that is trying to nurse the airplane through its first public performance.

A longtime Rutan supporter is quick to pronounce its appearance Reno's "story

of the year." Air race veterans privately wonder if the machine will last the

week. Reno seems an unlikely site to run a methodical test program.

Gold Sunday. Late in the afternoon the fans in Section Three

are on their feet as Steve Hinton, flying a crimson Lockheed T-33 pace jet,

leads the Unlimited's down the chute for the big race. For the next 10 minutes,

the world's fastest propeller-driven airplanes roar around the 9 1/2 mile course

eight times in loose trail. Midway through the race, Strega edges slightly closer

to Rare Bear. The mere prospect of a position change drives the crowd to fever

pitch. It never happens.

It is no picnic in the cockpit of Rare Bear, despite the

apparent ease with which Shelton maintains the lead. It is not just the periodic

onset of G forces in the wrenching pylon turns. The mismatch of propeller to

airframe demands constant special handling. The stubby prop blades set up such

a gyroscopic effect that every time Shelton pulls in or out of a turn, which

is roughly half the time spent in the race, the nose wants to slew around. "It's

the most physically demanding thing I've ever done," Shelton says later. "My

legs, upper thighs are tired from working the rudders. It's a heavy prop, and

that gives me a significant torque. When I pull G the nose wants to swing to

the right, then as the G eases off the nose wants to swing back to the left."

Strega spends the race nipping at Rare Bear's heels. Skip

Holm in Tsunami, a home built Mustang look alike, chases the two around the course,

hoping to pounce into the lead in the event either of them blows an engine.

(This will be Tsunami's last race. On the way home both the airplane and its

owner builder, John Sandberg, are lost when a flap actuator breaks and the airplane

corkscrews into the ground on approach to the Pierre, South Dakota airport.)

Strega spends the race nipping at Rare Bear's heels. Skip

Holm in Tsunami, a home built Mustang look alike, chases the two around the course,

hoping to pounce into the lead in the event either of them blows an engine.

(This will be Tsunami's last race. On the way home both the airplane and its

owner builder, John Sandberg, are lost when a flap actuator breaks and the airplane

corkscrews into the ground on approach to the Pierre, South Dakota airport.)

The Pond Racer sits out the day in a hangar. While the crew

had focused its attention all week on a series of problems with the right engine,

it was the left that surprised pilot Rick Brickert by throwing five rods and

bursting into flames as he was joining the formation for the Silver race's start.

This baptism of fire concluded the craft's first competitive appearance. (Months

later, Pond, Brickert, and pilot Dick Rutan are all upbeat. This was the Pond's

rookie season. They came just to see how it would do in race conditions. They

learned a lot. There is pair of bigger engines waiting back in Chino. They know

they have to shield the wiring. There will be other years....)

Destefani was right. His average speed on Sunday is faster

than Shelton's Saturday one-lap record of 477 mph. But it is not fast enough

to win. Shelton's average race speed of 481.618 is the new Gold race record.

Strega takes second with 478.68, and Tsunami is a close third at 478.14. After

a year of preparation and weeks of anticipation, the thing is over almost as

soon as it starts. An airplane covering 73 miles at nearly 500 mph behind a

4,000-horsepower engine and a propeller is a brief but marvelous thing to behold.

By early evening the grandstands are empty. Shelton, now a six-time champion,

has shown up at the press conference, said a few words of thanks to his crew

and sponsor, kissed the air race queen, and taken home $51,403 in prizes. It

is a token compared to the cost of running Rare Bear.

Traffic out of the airport is thinning. The Healer, a Mustang,

is parked near the pit entrance. The airplane is tired. A torrent of exhaust,

pressed back against the body of the airplane by the slipstream, has burnt its

mark. Iridescent bluing of heat on the polished met al blends with the reflections

of the deepening pink sky, giving the Mustang a fire-opal coat. The main gear

inner doors slowly ease down as hydraulic pressure ebbs.

A couple approaches, silent, almost reverent. Twenty-dollar

pit-pass bands on their wrists mark them as serious enthusiasts. They stand

at the angle off the nose where every definitive aspect of a Mustang looks best.

They are out of film, so they just stand, marveling, absorbing the moment.

They met by chance. They both liked airplanes. One of their

first dates was a Reno air race. When it was over, she said, "If we're still

together at this time next year, can we come back?" That was 12 years ago.

They have done a Reno ever since.

|

Two P-51 Mustangs approach the southern end of Runway 18/36 for what appeared to be a formation landing when the propeller of one Mustang caught the tail of the other, flipping it onto its nose. The aircraft in the rear tried to pull around the crashed aircraft and flipped over in the process. The pilot of the P-51 that ended up on its nose was able to walk away from the crash, the pilot of the green and silver P-51 was killed. (AirVenture 2007) |