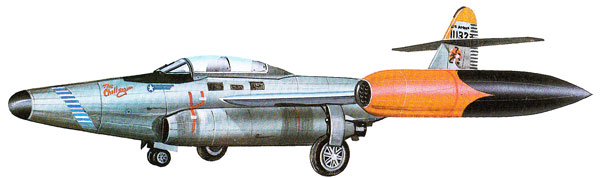

Northrop F-89 Scorpion All First-Generation All Weather Jet Interceptor

Possibly the most capable of the first-generation all weather jet interceptors, the Northrop F-89 was created in response to a USAF proposal for a a successor to the P-61 Black Widow. Entering server in 1950, the clumsy-looking Scorpion actually outlasted its contemporaries, the F-86D Sabre and the F-94 Starfire, in service. During the course of its career, the F-89's armament changed from cannons to rockets and nuclear missiles.

Northrop F-89 Scorpion

The first successful all-weather fighter to

be designed specifically for the role was

Northrop's F-89. Outlined in a ProPosal

made to the Air Force in December 1945, a

development contract was approved in May

1946. The mock-up passed inspection in

September, and the first of two prototypes

flew on August 16, 1948. The XF-89 carried

jettisonable wingtip tanks, but production

models had permanent tanks mounted to the

tips. The bulbous nose of the prototype was

also subject to change on the production

planes. The original intent had been to in-

stall a Martin nose turret of the type to be

used in the Curtiss XF-87, but this was

abandoned and conventional nose armament was mounted. Although large, the

fuselage was relatively slim, this due to the

tandem placement of the crew members. An

upswept tail led to the name "Scorpion."

The first successful all-weather fighter to

be designed specifically for the role was

Northrop's F-89. Outlined in a ProPosal

made to the Air Force in December 1945, a

development contract was approved in May

1946. The mock-up passed inspection in

September, and the first of two prototypes

flew on August 16, 1948. The XF-89 carried

jettisonable wingtip tanks, but production

models had permanent tanks mounted to the

tips. The bulbous nose of the prototype was

also subject to change on the production

planes. The original intent had been to in-

stall a Martin nose turret of the type to be

used in the Curtiss XF-87, but this was

abandoned and conventional nose armament was mounted. Although large, the

fuselage was relatively slim, this due to the

tandem placement of the crew members. An

upswept tail led to the name "Scorpion."

During flight testing, the ailerons on the XF-89 were replaced by a combination aileron/speed brake of the type used on the Flying Wings. Working conventionally as ailerons, the new controls divided top and bottom when used as speed brakes. Called "decelerons" by Northrop, they became standard equipment on all production Scorpions.

Production of the F-89A was approved on July 14, 1949, and 18 of this model were completed before an improved F'898 replaced them on the line. This model differed mainly in internal gear. Both the "A" and "B" models originally carried external balances on the elevators to dampen a high-frequency vibration. They were eliminated by development of an internal balance system. Thirty F'89B's were delivered before the first of 164 "C" types entered production. The first three production models carried six 20 mm cannons in the nose with the radar gear.

In 1951, an F-89B was redesignated YF- 89D and flown with two wingtip pods, each carrying 52 Mighty Mouse rockets plus fuel. Production F-89D's carried these rocket/fuel pods instead of the cannon armament. Six hundred eighty-two of these were built. Additional underwing tanks on the "D" increased its fuel capacity and range. With each model change, there was an accompanying uprating of the engines. The first Scorpion flew with two 4,000 lb. thrust Allison J35-A-15 engines. The F-89D was propelled by a pair of afterburning J35-A-33A's or -41's with 7,200 lbs. maximum thrust. The single YF-898 was an engine test bed.

The final production Scorpion was the F- 89H with tip pods constructed to carry three Hughes Falcon missiles and 2l Mighty Mouse FFAR rockets. An additional six FFAR's could be mounted beneath the wings. Two J35-,4-35's provided the driving force for this model. Modifications to permit launching of Douglas MB-1 Genie missiles changed the designation of 350 "D's" to F-89J's.

The design of the F-89F was a major departure from the Scorpion configuration. Although it reached the mock-up stage, technical problems involving the use of nuclear weapons led to its cancellation. Huge tanks were mounted at the midspan of the wing, these housing the main units of the landing gear, fuel and missiles. The fuselage was faired straight back from the front cockpit and a one-piece stabilizer was attached to the fuselage.

The F-89H has a span of 59 feet 8 inches and a wing area of 650 square feet with rip pods. Overall length is 53 feet 10 inches, height is 17 feet 7 inches. Empty weight is 25,194 pounds and gross weight is 42,241 pounds. The F-89H has a maximum speed of 636 mph at 10,600 feet. Range is 1,300 miles. Service ceiling of the F-89H is 49,200 feet.

On March 23, 1945, the USAAF's Requirement Division announced a competition for an all-weather fighter-bomber to guard the northern-most zones of the United States, with particular reference to Alaska where the severe weather conditions led to fighter interceptors being grounded when they should have been ready to defend American territory against possible attack.

The specification called for an aircraft

which was to be the Northrop P-61's immediate successor, a piston-engine fighter, but in December that same year the requirement was

changed to stipulate a jet powered aircraft. Bell, Consolidated, Douglas,

Goodyear, Northrop and Curtiss-Wright all entered projects in the con-

test and it was Curtiss-Wright whose submission, the four-jet XP-87

(q.v.) found the most favor, in part influenced by the fact that this

illustrious company was threatened with closure if it did not win the

order. Air Materiel Command also thought highly of John K. Northrop's proposal and in December, 1946, ordered two prototypes,

designating them XF-89.

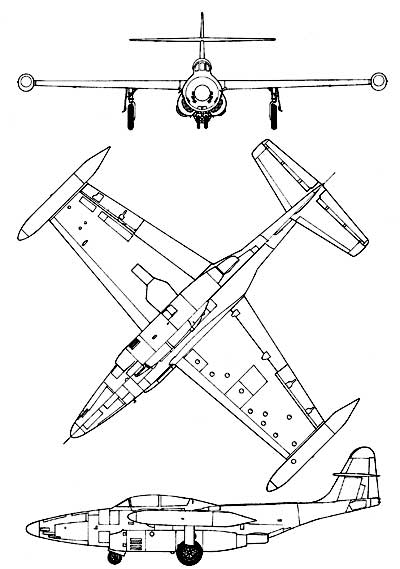

This was the last project on which Northrop himself collaborated before retiring from the day to day running of the business: the design was for a cantilever mid-wing monoplane, with a long, slim, elegant fuselage. In spite of the current trend in designs of that time for a swept-wing, Northrop's designers had opted for an unswept, laminar flow wing to ensure maximum stability at low speeds, important for a plane which would have to make frequent landings in bad visibility or all-instrument landings.

In the early stages of development, traditional ailerons and flaps were fitted to the wing trailing edge but later replaced by Northrop's patented "decelerons" which could divide and open up like a clamshell design and which could also function as normal ailerons or as airbrakes when they were fully opened. Removable tip tanks on the wings were an early design feature, later replaced with fixed tanks and eventually by pods containing rockets and fuel.

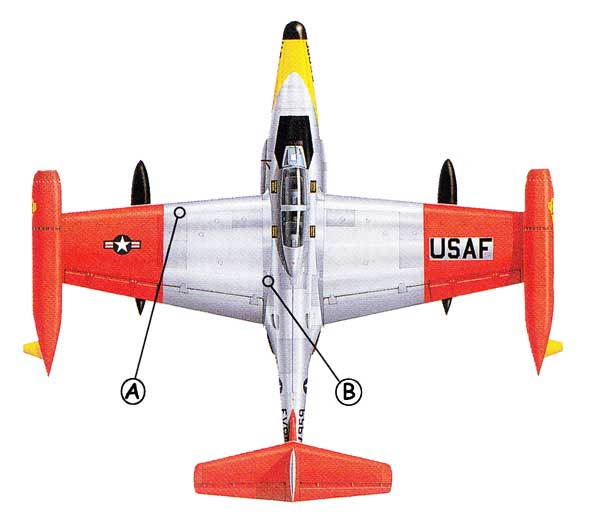

Two Allison J35-A engines with afterburner were mounted one on either side of the belly of the fuselage, only just under the wings with the air intakes mounted flush in front exactly in line with the engine nacelles. The semimonocoque construction aluminum alloy fuselage had an Al radar and four (later increased to six) 20mm cannons installed in the nose, but the cannons were completely deleted in the D variant, making room for another fuel tank and this version's only armament consisted of rockets.

The pressurized cockpit, seating the pilot and radar observer in tandem was positioned well forwards, had ejector seats and a large bubble canopy. The horizontal tailplanes had been lifted to a position half way up the vertical tailplane, well out of the way of the exhaust from the afterburners.

The retractable landing gear had unusually large diameter wheels. On August 16, 1946, Fred Bretcher took off from the Edwards AFB runway in the first XF-89 and flight testing began, with mainly positive results but the plane was clearly underpowered. In March, 1949, the plane was officially called the Scorpion (its designation having changed from XP-89 to XF-89 nine months previously), a name suggested by the ground crews at the base who thought the parked plane looked very much like that dangerous creature, crouched and ready to attack.

On July 14, 1949, the USAF decided to order 48 series F-89 aircraft when the Curtiss P-87 program had ground to a halt and to fill the gap until the Scorpion could enter ser- vice, Lockheed's F-94 Starfires (q.v.) were to be used, as they would be available at an earlier date. On February 22, 1950, the first XF-89 crashed while making its 102nd flight but this did not lead to any change in the orders already placed. On June 27 that year John J. Quinn gave the second prototype, designated YF-89A, its maiden flight; this plane differed greatly from the XF-89 which had been destroyed.

The airframe had undergone an 80 percent redesign, the fuselage had been lengthened and the nose made more sharply tapering. The YF-89A was also equipped with AN/APG-33 radar. The USAF was able to take delivery of the first eight F-89As before the end of 1950; these were armed with six 20mm cannons and had Hughes radar installed.

Production continued with the remaining 40 F-898 version, differing only in detail changes to their avionics and, in September 1951, switched to the F-89C which had new, more powerful engines, a different tailplane and a new Hughes E-1 fire-control system. Production of a batch of 164 F-89Cs was in full swing when an F-89C broke up in flight at the International Aeronautical Exhibition at Detroit, on September XF-89 (46-678) Scorpion prototype. 22, 1952.

Public reaction was extremely strong and all Scorpions were grounded until the fault was detected in the airframe at the wing-root. Strengthening and modifications were carried out retrospectively on all Scorpions which were recalled to the plant, while these changes were applied to aircraft still in production. After a few more unfortunate accidents, the F-89 turned out to be a tough, reliable airplane.

The most numerous D variant went into production towards the end of 1951, with a total of 682 being built. These F-89Ds had 104 air-to-air rockets (instead of the previous versions cannons) guided by the new Hughes E-6 fire-control system; they could be launched singly or simultaneously, giving unprecedented fire-power.

September, 1955, saw the first series F-89H aircraft coming off the assembly lines and this production batch totalled 155. The series H planes were equipped with more powerful engines, the Hughes MG-12 fire-control system and were also able to carry and launch six Falcon missiles, besides the usual rockets.

The H proved to be the last distinct F-89 variant, since the F-89J was effectively a F-89D equipped to carry and launch Genie and Falcon missiles; as a result the Scorpion went down in history as the first American fighter capable of launching air-to-air nuclear missiles.

All 1,050 of the Scorpions produced, with the exception of the experimental and test planes, were deployed by Air Defense Command, equipping more than 30 Fighter Interceptor Squadrons. The first F-89Bs reached 84th Fighter Interceptor Squadron in February 1951 and 82nd FIS received theirs a little later. F-89Cs entered service with 27th,74th and 433rd FIS from 1952 onwards; 57th Squadron, based in Iceland, took delivery in 1953, as did 65th and 66th, based in Alaska, and 438th Squadron. F-89Ds were flown from 1954 onwards by 18th, 61st, 64th, 318th, 337th and 449th based in Alaska, as well as 497th FIS. 11th,58th and 59th Squadrons, based in Labrador, took delivery of F-89Ds and H versions from 1955; other units to receive these variants in that year were: 68th, 75th76th,83rd 32lst, 432nd,43'7th,445h,460th and 465th; from 1956: 98th FIS; 1957:29rh,54th and 319th; 1959: l5th and 49th. ln 1961 all Scorpions were taken out of service with the USAF and relegated to use by the Air National Guard, whose squadrons flew them for many F-89A (49-2435), the fifth series aircraft.

|

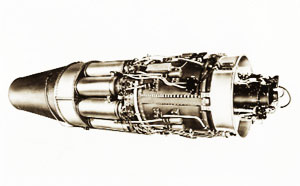

The TG-180 engine designed by General Electric was the axial-flow jet engine used in F-89A Scorpions and F-84 Thun. |

Specifications for the Northrop F-89 Scorpion

|

Crew: 2 |

|

|

| A: Mounting the engines under the fuselage resulted in a high rate of FOD (foreign object damage) and the F- 89 was often referred to as the 'Hoover Model F-89' because of this trait. | B: A major factor in the stability of the Scorpion was its straight, laminar flow wing. lt made take- offs and landings considerably easier. |

|

||

| A: Throughout their careers, the F-89s remained primarily in natural metal finish. To reduce glare and prevent pilot distraction, the area just forward of the windscreen was painted black. | B: Sitting under the sliding bubble canopy were a pilot and a radar operator. Despite its drawbacks, the F-89 was rock-steady in the air. | C: The 'D' model introduced new armament in the form of the FFAR (folding fin aircraft rockets). Crews were trained to fire these rockets in three salvoes. |

| D: F-89Ds introduced a longer and slightly slimmer nose profile. The six-cannon arrangement of earlier variants was dispensed with and extra fuel carried in the nose. | E: An unusual feature of the F-89 was its large- diameter main wheels. They were deemed necessary because of the shape of the wing and the F-89's considerable weight. | F: Like the Canadian CF-100 Canuck, the Scorpion featured a mid-mounted tailplane with zero dihedral. The XF 89 had encountered severe turbulence and buffeting at high speeds. |

|

A 2006 photo by Mark Sublette, looking west at the remains of an F-89D Scorpion (65-NO53-2584) & an A-4A Skyhawk on Peel Field. |