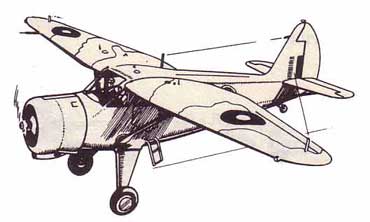

Stinson V-77 Reliant "Gullwing"

The prototype of Reliant was first flown in July of 1942. Needing a navigational trainer to bolster the training program, the USAAF ordered a batch of the redesigned "Reliant," but, strangely enough, the need was not all that critical after all and nearly all of the Reliant (AT-19s) were shipped overseas. A few did stay in this country and a few were flown off to Canada, but the bulk of the AT-19s went to England to serve in the Royal Navy's "Fleet Air Arm." (below)

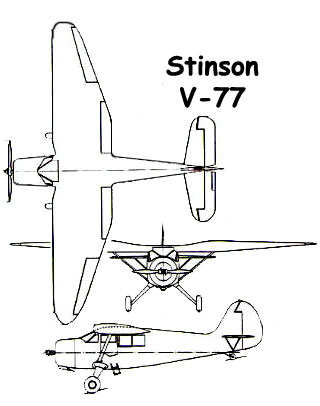

An easy way to tell the difference between a Straight Wing Reliant and a Gull Wing Reliant are the wing struts. The Straight Wing Reliant's have two struts on each side, the Gull Wing Reliant's have a single strut for each wing.

I saw that there is an FG Stinson Gullwing in the future. I think that's great! My grandpa used to have one. He stopped flying a few years ago because of heart problems and sold the plane to a local air museum. If you need any pictures of the plane I can get some. I am a member of the air museum where the plane "lives" now. My grandpa might also still have photos from when he had the plane restored. V Cleveland

Stinson V77 Reliant

The

AT-19 version as "Reliant 1" was a five-place airplane

used to ferry personnel, the AT-19A as "Reliant 2" was

equipped with radios and used to train navigators; the AT-19B

as the "Reliant 3" was used for observation and photo-work,

while the AT-19C as "Reliant 4" was used mostly for

cargo hauling and air express shipments. The "Reliant 2 and

3" were not actually war-machines, but were used to train

British military personnel in the arts of navigation, radio communication,

and aerial photography.

The

AT-19 version as "Reliant 1" was a five-place airplane

used to ferry personnel, the AT-19A as "Reliant 2" was

equipped with radios and used to train navigators; the AT-19B

as the "Reliant 3" was used for observation and photo-work,

while the AT-19C as "Reliant 4" was used mostly for

cargo hauling and air express shipments. The "Reliant 2 and

3" were not actually war-machines, but were used to train

British military personnel in the arts of navigation, radio communication,

and aerial photography.

Five hundred of the AT-19 series were built into late 1943 and nearly all had been sent out on a lend-lease basis. Extremely rugged, the AT-l9 ("Reliant") served the British well and the attrition rate was very low; more than 350 were shipped back to the U.S.A. after the war waiting to be declared surplus.

In June of 1946 some 350 of the various AT-19 were on the surplus airplane listings and were selling for $1500 to $2500 (cash only) each, depending on the airplane's condition. Needless to say, they were bought up in no time and reconditioned to qualify for civil use under this ATC approval as the V-77. The Stinson plant in Wayne, Mich. did most of the reconditioning, and some of the airplanes rolled out in nearly new condition. Built tough to lead a rugged life, many of them did just that, and were used extensively "in the bush." The classy-looking ones you see nowadays at air meets are just showpieces.

From 1933 to 1941, Stinson delivered 1,327 Reliant's ranging from the SR-1 through the SR-10 each variation building upon its predecessor with upgraded engines and design refinements. The Stinson Reliant SR-10, introduced in 1938, was considered the ultimate, featuring leather upholstery, walnut instrument panels, and automobile-style roll-down windows. |

The Stinson "Reliant" model V-77 as modified from a military-type AT-19 was a high-winged cabin monoplane with seating normally arranged for five. Like the many "Reliant's" before it, this was a big and impressive airplane, the size of which was not really appreciated until you stood under it. The V-77 was rather massive, but yet proportionate and graceful even parked. Versatile as any "Reliant" ever built, the V-77 was often operated "in the bush" on wheels, skis, or pontoons, and did an admirable job in either case.

As powered with the 9 cyl. "radial" Lycoming R-680-E3B engine of 300 h.p., the V-77 had a marvelous performance despite her size, and had a very deliberate character. Control was light and response was good, but she did everything in her own time, and she knew best. Normal flight was unwavering with a good, solid feel and she would fly hands-off (with an occasional nudge from the pilot) for the longest time if "trimmed" properly.

The V-77 was honest, predictable, and had no low-speed tricks, but it was a lot of airplane and it required almost continuous management for best results. Some have said the V-77 had to be catered to to keep her in a good mood.

The construction details and general arrangement of the model V-77 were typical to that of the SR-10 series, and varied only in basic detail The V-77 had room enough for 5, but fuel load had to be reduced if any large amount of baggage was carried. A large stepladder and entry door were on the left. Interiors with roll-down windows in front varied from airplane to airplane; some were done up plush to carry 4 or 5, and others had stripped cabins that were lined and fitted to carry cargo.

The baggage compartment behind the rear seat had 12 cu. ft. capacity for up to 105 lbs. Fuel capacity was normally 76 gal. (38 gal. tank in each wing-root), but capacity to 126 gal. was optional.

The wing flaps were vacuum-operated and would bleed-up for a go-around; some airplanes were later modified to all-electric operation.

The robust cantilever landing gear of 9'8" tread used long-stroke

"oleo" shock struts and 7.50x10 wheels with 8.50x10

(6-ply) tires and toe-operated hydraulic brakes; the full-swivel

tail wheel had fore-and-aft lock. All controls were on ball bearings

and had aerodynamic balance; elevator had an adjustable trim tab.

The robust cantilever landing gear of 9'8" tread used long-stroke

"oleo" shock struts and 7.50x10 wheels with 8.50x10

(6-ply) tires and toe-operated hydraulic brakes; the full-swivel

tail wheel had fore-and-aft lock. All controls were on ball bearings

and had aerodynamic balance; elevator had an adjustable trim tab.

A Hamilton-Standard constant-speed prop, electric engine starter,

engine-driven generator, 12V battery, oil cooler, carburetor heater

& air filter, engine exhaust muffler, cabin heater muff, normal

set of engine & night instruments, airspeed indicator, compass,

vacuum pump, fuel gauges, dual control wheels, bonding & shielding,

navigation lights, cabin lights, parking brake, map & gadget

pockets, fire extinguisher bottle, assist ropes, seat belts, and

first aid kit were generally included as standard equipment.

Stinson Reliant's became the mainstay of Alaskan bush operators

for more than a quarter of a century. The large flaps enabled

a pilot to land thousand pound loads on unimproved sand bars.

|

The A.A.A. pilots, using Stinson SR-SOF aircraft, were eventually able to perform the in-flight pick-ups and deliveries at a speed of 190 mph. Early-developed shock absorbing equipment was later replaced by an electrically operated winch device which absorbed the shuck of attachment more efficiently. A pick-up plane and ground-rig are preserved in the National Air and Space Museum. |

Note an easy way to tell the difference between a Straight Wing Reliant and a Gull Wing Reliant are the wing struts. The Straight Wing Reliant's have two struts on each side, the Gull Wing Reliant's have a single strut for each wing. The SR-5A was powered by the 245HP Lycoming R-680 engine.

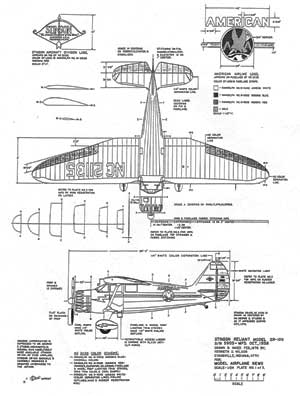

There were 3 basic versions of the SR Reliant series airplanes.

The SR, SR Special, SR-1, SR-2, SR-3, SR-4, SR-5 and the SR-6 together

are one version commonly known as the "Straight Wing"

Reliant's. A total of 287 straight wing Reliant's were built by Stinson.

Second SR series were the SR-7, SR-8, SR-9 and SR-10 which together

are known as the "Gull Wing" Reliant's. A total of 488

Gull Wing Reliant's were built by Stinson, all prior to World War

II. Last Stinson Reliant was the V-77 which was a modified SR-10

built during World War II primarily for the British. The American

military did use some of these aircraft under the designation AT-19.

A total of 500 V-77/AT-19 Reliant's were built by Stinson during

World War II. The V-77 is actually a Vultee model number, by this

time Stinson had been purchased and was the Stinson Division of

Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corporation.

The Stinson Aircraft Company was founded in Dayton, Ohio, in 1920 by aviator Eddie Stinson 9 years after he learned to fly with the Wright Brothers. In 1925 Stinson would make Detroit, Michigan, the base of operations for his company. Over the next three decades, more than 13,000 aircraft would carry the Stinson brand. The Stinson Reliant was a rugged aircraft built of fabric-covered welded steel-tubing structures with a single strut-braced double-tapered wing, and one of the last of the tail draggers. From 1933 to 1941, Stinson delivered 1,327 Reliant's ranging from the SR-1 through the SR-10 each variation building upon its predecessor with upgraded engines and design refinements. The Stinson Reliant SR-10, introduced in 1938, was considered the ultimate, featuring leather upholstery, walnut instrument panels, and automobile-style roll-down windows. |

Veteran aviator Edward "Eddie" Stinson founded the Stinson Aircraft Corporation in Detroit, Michigan

and, in 1926, introduced the Stinson Detroiter, a rugged monoplane

with sophisticated features for the time: a heated, sound-proof

cabin, wheel brakes, and a starter. In 1928, the Stinson Aircraft

Company produced the SM-2 Junior,

a three-to four-place high-wing cabin monoplane for corporate

and private use. In 1929, Stinson merged with E.L. Cord and

the Cord Corporation for more secure financial backing. This

merger allowed Stinson to offer its aircraft at lower prices

and still develop new designs, the 1931 Model W and the 1932

Model R-2/3 series, the direct forebears of the famous Reliant

series.

Veteran aviator Edward "Eddie" Stinson founded the Stinson Aircraft Corporation in Detroit, Michigan

and, in 1926, introduced the Stinson Detroiter, a rugged monoplane

with sophisticated features for the time: a heated, sound-proof

cabin, wheel brakes, and a starter. In 1928, the Stinson Aircraft

Company produced the SM-2 Junior,

a three-to four-place high-wing cabin monoplane for corporate

and private use. In 1929, Stinson merged with E.L. Cord and

the Cord Corporation for more secure financial backing. This

merger allowed Stinson to offer its aircraft at lower prices

and still develop new designs, the 1931 Model W and the 1932

Model R-2/3 series, the direct forebears of the famous Reliant

series.

Powered by Lycoming or Wright radial engines in the 200 to 300 hp range, these aircraft combined solid and reliable performance with plush cabin interiors. In 1933, Stinson delivered the SR-1 and SR-2, and with a progression of refinements and engine upgrades, the series continued from the SR-4 to, in 1938, the SR-10. The SR-10s were truly the limousine class of personal transport with fine leather upholstery, walnut-faced instrument panels, and roll-down side windows similar to automobiles.

The SR-10 series was produced until the beginning of World War

II when existing Reliant's served assorted utility missions as

UC-81s. Stinson later produced 500 military versions of the

Reliant's as the AT-19/V-77 for the British Royal Navy which

used them mostly as instrument trainers along with utility passenger

carrier and photo-reconnaissance work. About 350 AT-19/V-77

were returned to the United States after the war and refurbished

by Stinson for the post-war civilian market. Many of these are

still in existence today and can be seen at fly-ins of antique

aircraft.

The Reliant was a ruggedly built airplane made mostly of welded

chrome-mol steel tubing structures covered with fabric. The

fuselage framework was faired to shape with wood formers and

fairing strips. The fuselage forward of the doors was covered

and faired with a duralumin sheet that included removable engine

accessory panels. The single strut-braced, double-tapered wing

was built with a girder-type spar with riveted square aluminum

tubing ribs attached to the spars with riveted gussets.

The leading edge was wrapped with duralumin sheet and the ailerons and slotted vacuum-operated wing flaps were of similar construction. The fabric-covered tail assembly was built of welded steel tubing with aerodynamically-balanced control surfaces and an adjustable horizontal stabilizer. The aircraft had a nine-cylinder Pratt and Whitney Wasp Junior radial that developed 450 hp for take-off and it was usually equipped with an aluminum two-blade Hamilton Standard constant speed propeller.

The wide-tread cantilever landing gear was equipped with low-pressure tires and hydraulically-operated disc brakes. The SR-10F Reliant came equipped with a full complement of options including: instruments for poor weather flight, 12-volt battery system, electric starter, cabin heater and ventilation system, ash trays, cabin assist straps, shatter-proof glass, roll-down windows, navigation lights, landing lights, and leather upholstery. This final version of the Reliant was re-engineered by famed racing plane designer Gordon Israel with many refinements, such as retractable cabin entry steps.

May 7, Guido has started the V77 Stinson Reliant (more below) |

|

|

|

Three

more beta photos about a week later. Look how Guido has rounded

the nose BUT still needs to sort out the front of the cowling..

Watch this space.. Three

more beta photos about a week later. Look how Guido has rounded

the nose BUT still needs to sort out the front of the cowling..

Watch this space.. |

The

following is an article that was sent in to us...

The

following is an article that was sent in to us...

Antique airplanes were still fairly inexpensive and parts more available. In fact, most had yet to be restored even for the first time, as they were still on the first fix-enough-to-keep-it-flying go around. This must have been one of the first three or four pilot reports I penned. It's interesting to read my own words over three decades after the fact.

I've edited nothing in this text, so you're hearing the words

of a twenty-seven-year-old writer/photographer just beginning to find

his way. Also, magazines like Air Progress were limited to four pages

of color per issue and the black and white reproduction was awful.

Things in that area have come a long way.

The Reliant was built in the days when airplane was spelled with a

capital "A." People liked to travel first class, in style,

with all the comforts of home. Nobody was going to go anywhere if

they had to suffer discomfort. When the airplane progressed to the

stage where it could offer more than a rough ride and a case of pneumonia,

big business began to view it in a completely new light. No longer

a daredevil machine, it was now a means of travel. Affluent travelers

demanded comfort even in the air, and so, the cabin airplane started

out as a summer home with wings.

The foregoing philosophy yielded many beautiful ships: the Staggerwing

Beech, the Howard DGA-15, the Noorduyn Norseman, and the Gullwing

Stinson Reliant. Before technology brought this golden era to an end

after World War II, these planes ruled supreme as the original mini airliners.

These queens of the low-frequency airways have become favorites among

the more ambitious restorers. Ambitious, because recovering a Reliant

or a Staggerwing is like trying to recover a house.

Although

highly tapered wings supposedly lead to tip stall you can't prove

it by the Reliant. Its stalls are super benign and well mannered.

Although

highly tapered wings supposedly lead to tip stall you can't prove

it by the Reliant. Its stalls are super benign and well mannered.

The model R Reliant was born in 1931 as a redesigned, hopped-up version

of the older Stinson Junior. Bob Ayer, of Gee Bee fame, had come on

board, specifically to get speed out of the Junior. The cantilever

gear and new fuselage shape were his ideas. The original Reliant wing

was the straight barn door of the Junior, but as the design was refined

through to the SR7, the platform was changed to a birdlike shape and

the thickness was made to taper out to the struts and then back down

out toward the tips, giving it a gull shape-the Gullwing Stinson was

created.

The crash survivability of a Reliant must be fantastic, judging from

its construction. The fuselage is a maze of steel tubing; the wing

spars are also a tubing truss. A thousand years from now some archaeologist

will dig up the fossilized remains of a Reliant and think he's come

upon the skeleton of a huge prehistoric bird.

There are conflicting theories and tales about the heat treating of

the steel truss works of the Reliant and the problems involved in

repairing certain parts. According to Fred Morris, in the civilian

SR series, only the gear is heat treated, while in the military version,

the V-77, the wing spars are heat treated.

To make a 3,800-pound, 42-foot, high-wing airplane perform takes a

lot of brute force; the force ahead of 39's firewall is a Lycoming

R-680-9 with 300 hp. Nothing carries the old time airplane sound quite

as well as a big radial at idle, and the Reliant's big round engine

certainly has that sound.

Fred and John take great care in keeping their monster machine well-groomed;

the engine is as clean looking as it is clean sounding. Because of

the sheer mass in the engine package, and the sculptured cowl, one's

eyes automatically track straight to the engine when the airplane

is first sighted. Its blunt, chromed nose and the many-cylindered

round engine are a good introduction to the rest of the airplane.

Going back down the fuselage, and stepping around the barrel-sized

pants, we climb aboard via a short stepladder. The ladder isn't there

to make boarding easier, it's there to make boarding possible. The

bottom edge of the door is nearly waist high—it would take a

second-story man to make it up without the ladder.

The door is thick and the opening it covers is large. The interior

resembles a well-appointed sitting room. The rear seat accommodates

three normal-sized men with a minimum of squashing and a maximum of

legroom.

The impression of size heightens as you move forward and settle down

in the driver's seat, with the huge, polished, round wheel in front

of you. The interiors of most restorations are disappointing, especially

in regard to details that go toward making a panel appear clean. The

inside of 39 is just as sharp as the outside; the panel is a work

of art. Its black enamel is spotless and every screw head, every instrument,

looks as if it has never been touched. The 1936 Ford-type panel grouping

has flight and engine instruments completely separated and mounted

in recessed panels. The width and height of the panel and the elbow

room on the flight deck give one the impression of being in an old

airliner or perhaps on the bridge of a ship.

The Stinson is started with the prop in the low rpm position. The

big 300 Lyc took a bit of priming to coax to life, but it eventually

belched the oil it had collected in the lower cylinders, blew a cloud

of smoke, and settled into that low, throbbing rumble that raises

goose bumps.

Almost all taxiing and tight maneuvering on the ground is done with

brakes because the tail wheel is full swiveling with a lock for straight

ahead. Visibility is adequate, but just barely. There is a tremendous

blind spot to your right because the other side of the cockpit is

so far away that you have to S-turn tightly to see anything on your

right front quarter.

The Reliant's, like all airplanes of their day had an art deco flair

to their panels that would be a shame to smudge with stuff like modern

radios and gyros.

It seemed as if every airplane in the country picked this day to shoot

touch-and-goes, and a Reliant is definitely not the perfect vantage

point for monitoring traffic. It has too much airplane and not enough

windshield.

Once traffic decided to let us go, we lined up and I reached under

the seat and pushed the tail wheel lock down to lock the wheel in position.

Fred had told me to pick the tail up at about 65 mph, and to lift

off at about 80.

I guess I'm used to an airplane that tells me when it's ready to lift

its tail, but there was absolutely no feeling in the controls that

said the tail was light and ready to go. Fred had to tell me when

to push, and then he had to help me because I wasn't being forceful

enough. The same is true of lifting off. When 80 mph comes around

on the dial, it takes a fairly good tug to get 39 off the deck. Fred

says she'll fly herself off, but it takes a lot less runway if you

forcefully pick it up.

In

a cruise climb of 100 mph, we were getting better than 1,000 fpm with

full tanks and three aboard. Some airplanes let you know that you're

climbing fast because they grunt and groan and show how hard they're

working. Not the Reliant. It climbs as effortlessly and as smoothly

as a hot-air balloon. The only indication of vertical velocity is

the rapidly vanishing ground.

In

a cruise climb of 100 mph, we were getting better than 1,000 fpm with

full tanks and three aboard. Some airplanes let you know that you're

climbing fast because they grunt and groan and show how hard they're

working. Not the Reliant. It climbs as effortlessly and as smoothly

as a hot-air balloon. The only indication of vertical velocity is

the rapidly vanishing ground.

All size, or bulk, disappeared as soon as we left the ground. At cruise,

it handles better than many so-called sports/ trainers. I was really

surprised how it responded to aileron and elevator. It's no fighter,

but it doesn't need two hands, which the tractor size wheel would indicate.

The roll rate and control feel is similar to a Cessna Cardinal, which

is saying a lot considering that the Reliant weighs about twice as

much.

In cruise, N18439 takes quite a nose-down attitude to maintain level

flight. This attitude helps forward visibility immeasurably, but the

cabin roof and wing roof juts far enough forward that a lot of sky

is hidden. In the 1930s, traffic problems were not what they are today,

so visibility wasn't quite as important. Most airplanes of this era

have the same problem.

This sucker redefines the term "big and beautiful." Its

300 hp R-680 Lycoming appears almost small on its wonderfully sculptured

nose. The cantilever gear system uses inboard shock absorbers a system

that would show up again on the 108 series Stinsons.

Radials don't make much noise, and the cabin walls are so thick that

the noise level is about as low as it could be. Normal conversation

was easy one of the reasons the Reliant was so popular with the prewar

"in" crowd.

No pilot report is complete without a thorough investigation of the

stalls, even though few airplanes exhibit really hair-raising characteristics.

The Reliant is like the rest, even though it's like full-stalling

a house. The nose comes up, the airspeed goes down, the airplane shakes,

the nose drops, and forward pressure and power remedy the situation.

No sweat! Old-time bush pilots used to be able to land Reliant's in

unbelievably tight corners, partially because of its power and the

absence of low-speed tricks. I later proved that it takes a better

pilot than me to park a Reliant in a pea patch.

One thing about the Reliant that really surprised me is that with

all that wing, I expected it to float down, but its glide is more

of a trajectory than a glide path. With zero power it bottoms out at

around -1,500 fpm, but with the power back and the vacuum-operated

flaps out, the VSI needle goes past 2,000 fpm like a shot. You wouldn't

have a whole lot of time to pick out a field when this one quits!

Keeping in mind that we were going to come to a screeching halt when

I brought the power back, I tip-toed into the pattern. I gave myself

plenty of room and moved the base leg out a bit so I could make a

power approach. Fred told me to make final a little high and add flaps.

I, naturally, overdid it.

In a normal airplane I would have floated right past the field, but

when those flaps came out and the nose pitched over, the runway came

right back up where it should have been. I held 85 mph most of the

way down final, slowing it to 80 mph over the fence. Fred says he

always wheels it on, so I thought I would, too. At least, that's what

I thought. As the speed fell and I tried to level off, the control

forces seemed to build up and were as heavy as they had been on takeoff.

What was supposed to have been a thistledown landing turned out to

be the original Jersey bounce. I dribbled and skidded and waddled

down the runway on the mains. Fred says he puts it on main gear first

and lets the tail fall immediately, rather than trying to hold it

up. I didn't get a chance to test his technique. My arrival was so

sloppy I couldn't really tell whether or not it was easy to land.

My only conclusion is that it must be fairly forgiving, all things

considered, or I would have wrapped it up right there. Fred said that

he had no trouble transitioning and he really had a transition.

At 130 mph and 15 gallons an hour, the Reliant is one of the classiest,

most luxurious ways of traveling. Each monthly issue of Trade-A-Plane

shows at least a couple Reliant's for sale, averaging between $4,500

and $8,000 (Ed: not any more!). You can move at the same speed, carry

more people, and have twice the fun of a Cherokee, for little more

than half the price. You do have to worry about fabric and oil leaks,

and a few parts are hard to find, but one look at the early morning

sun bouncing off that big cowling makes it all worth it. Besides,

you can always set up housekeeping in it.

From this angle it's easy to see how the Reliant got the nickname,

"Gullwing."

|

Even the Nazi loved the Gullwing! |

Specifications

|

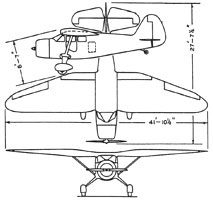

Crew: one, pilot Capacity: 3 to 4 passengers Length: 29 ft 6 in Wingspan: 41 ft 10 in Height: 9 ft 2 in Empty weight: 2,530 lb Useful load: 1,345 lb Powerplant: 1× Lycoming, 245 hp / Wright, 350 hp / Pratt & Whitney, 450 hp Performance Cruise speed: 152 mph Range: 650 mi Service ceiling: 12,700 ft |