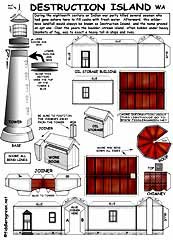

Destruction-Island WA - $$4.95

During the eighteenth century an Indian war party killed several seamen who had gone ashore here to fill casks with fresh water. Afterward, this wilderness landfall would always be known as Destruction Island, and the name proved an apt one. Over the years the boulder-strewn island, often hidden under heavy blankets of fog, was to exact a heavy toll in ships and lives.

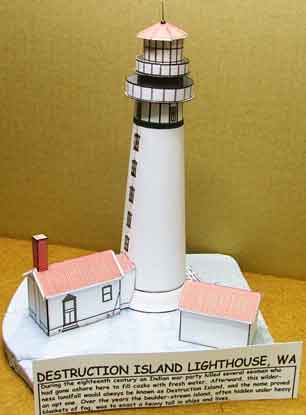

Destruction Island Light House, Wa

During the eighteenth century an Indian war party killed several seamen who had gone ashore here to fill casks with fresh water. Afterward, this wilderness landfall would always be known as Destruction Island, and the name proved an apt one. Over the years the boulder-strewn island, often hidden under heavy blankets of fog, was to exact a heavy toll in ships and lives.

During the eighteenth century an Indian war party killed several seamen who had gone ashore here to fill casks with fresh water. Afterward, this wilderness landfall would always be known as Destruction Island, and the name proved an apt one. Over the years the boulder-strewn island, often hidden under heavy blankets of fog, was to exact a heavy toll in ships and lives.

Destruction Island Light House (1891)

As early as 1855 the Lighthouse Board saw the need for a powerful navigational light to warn ships away from Destruction Island. Building a lighthouse on this remote and extraordinarily rugged offshore site, however, was a daunting task. Although Congress set aside $45,000 for the project, it was deemed impractical, and the money was spent elsewhere.

Spurred on by a sharp increase in shipping along the Washington coast and the lengthening list of wrecks on the island's jagged rocks, work on the lighthouse finally got underway in 1888. Materials had to be brought ashore in small boats from a tender anchored in a cove near the construction site, and the tower, dwelling, and outbuildings took nearly three years to build. At last the steam-driven fog signal began to sound in November 1891, and one month later, keepers lit the lamps inside the station's first-order Fresnel lens. Although the Destruction Island station was automated in 1963-much to the relief of its lonely Coast Guard keepers-its classic lens remains in operation.

Travel information: Destruction Island Lighthouse is off-limits to the public, but it can be seen from a parking area along U.S. Highway 101, about a mile South of Ruby Beach.

Destruction Island :

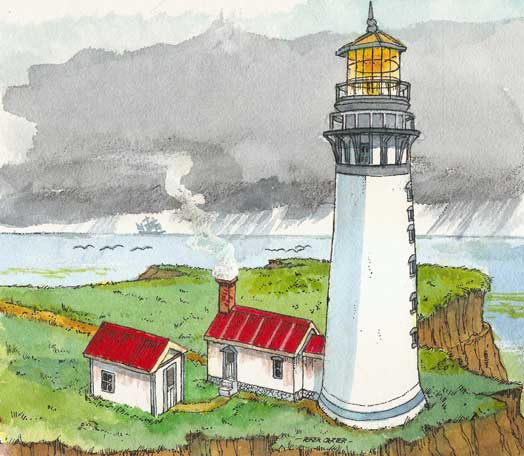

Remote and uninhabited, except by healthy numbers of seals, seabirds, and rabbits, half-mile-long Destruction Island rises from the Pacific, three miles off the northwest Washington coast. Its steep, irregular sides are surrounded by a wave-lashed jumble of craggy rocks and ledges which keep the outlying spot almost unapproachable even in calm weather.

Despite the seeming barrenness, the interior of 30-acre Destruction Island forms a broad, grassy terrace, one that generations of local Native Americans found well-suited to growing potatoes. Tribes people often remained here during the warm weather months while they fished the surrounding waters. When the Lighthouse Board first reviewed possible sites for lights along Washington's Pacific coast, it selected Destruction Island as a prime candidate. In 1855, Congress appropriated $45,000 for a major beacon here, but officials allocated the money to other jobs and the light was never built.

Thirty years later, lawmakers earmarked a pair of appropriations totaling $84,000, expressly for a station on Destruction Island. Beginning in 1888, the Army Corps of Engineers supervised construction of a 94-foot masonry tower on the southern part of the land and had it sheathed with curved iron plates for protection against the elements. The new lighthouse, which went into full operation 31 December 1891-included the lighthouse, two dwellings, a barn, fog signal house, and several smaller outbuildings.

The walls of the sturdy conical tower taper from 48 inches at ground level to 18 at the parapet. The black lantern cage enclosed a first-order Fresnel lens, whose 1,176 beveled prisms magnified a white light that could be seen 24 miles at sea.

Charles Zauner was appointed Destruction Island's first civilian keeper. In the interests of economy. The station was automated in 1968. Destruction island has no public access.

Destruction Island

Lighthouse was built between 1889-91, all building materials brought

in by lighthouse tenders, lighters into the rough landing area

and hauled up to the isle's plateau. It was a laborious undertaking

and the builders did a splendid job on the 94 foot masonry tower,

which, because of its isolated location, was encased in iron plates.

The Army Corps of Engineers supervised the building of the station

for the Lighthouse Service, and when one considers the difficulty

of water transport and the landing of materials in a spot tantamount

to an obstacle course of river rocks, the accomplishment is more

readily appreciated.

Destruction Island

Lighthouse was built between 1889-91, all building materials brought

in by lighthouse tenders, lighters into the rough landing area

and hauled up to the isle's plateau. It was a laborious undertaking

and the builders did a splendid job on the 94 foot masonry tower,

which, because of its isolated location, was encased in iron plates.

The Army Corps of Engineers supervised the building of the station

for the Lighthouse Service, and when one considers the difficulty

of water transport and the landing of materials in a spot tantamount

to an obstacle course of river rocks, the accomplishment is more

readily appreciated.

The completed tower was fitted with a first order Fresnel measuring 8.9 feet in height, 6.2 feet in diameter, composed of 24 bulls eyes and a total of 1,176 prisms. One writer described the scintillating beauty of the lens as a "fairy tale greenhouse." All the components were landed in crates and assembled in the lantern house. By the time the light was put in operation in 1891, nearly three years had passed, including the erection of derricks and hoists to lift the materials up to the island plateau. The tower sat on a sandstone base with massive masonry walls four feet thick on the lower levels tapering to 18 inches beneath the lantern house. The spiral staircase circled artistically upward 115 steps. On completion, the Light List described the station in the following terms:

White conical tower; black lantern and parapet; two oil houses, 75 feet; two dwellings, 550 feet, a barn 650 feet, ENE, and a fog-signal building 130 feet northwesterly of the tower; buildings white with brown roofs.

The boiler-fed first class steam siren in later years was replaced by a diaphragm horn which caused the station bull to go on a rampage thinking he had a rival for the cows grazing in the pasture. He knocked down several fences and dug up mounds of sod before he could be controlled.

Visitors were almost nonexistent during the years the station was manned except for those on special missions. Some families dwelled on the island and made the best of their lot despite the isolation, separated by a 20 mile trip by water from LaPush. It was a hard but rewarding life for those who lived there, and it was a naturalist's paradise with an abundance of sea creatures and birds. The elements of weather were extremely harsh at times. According to a report in the 1930's, a fierce gale sent seas crashing up to the plateau of the island, doing some damage to the station outbuildings, and cracking some of the windows in the tower.

Though there exists a rugged switchback trail from the landing, when the station was manned a derrick and boom with an attached box-like conveyance were employed for raising and lowering personnel and supplies. In an emergency, if something goes wrong at the lighthouse, maintenance crews can be flown in by helicopter, though occasionally Coast Guard motor lifeboats from the Quillayute station are used for the purpose. Automation came to the station in 1968, which left the place void of life for the first time in seven decades. Four keepers were originally attached but when the Coast Guard manned the facility there was frequent rotation; some personnel had their wives reside on the island. The station mascot for several years was a small deer named Bambi. The early keepers raised much of their food on the island and kept cows, pigs and chickens. The soil was sufficient for raising vegetables.

Before the lighthouse was constructed, by executive order of June 8, 1866, Captain James S. Lawson went to the island in the U. S. Coast Survey ship Fauntleroy and officially reserved it for lighthouse purposes. No bids were let however, for 22 years thereafter. The initial outlay for the station, monetarily speaking, was $45,000, but the difficulties incurred demanded almost twice that amount before the station was completed. The work was so tedious the first winter that by the end of the year only one house was completed, part of the second dwelling, a barn and cistern. Some initial work had also been accomplished on the water catchment basin and a landing area, but bitter weather soon put the damper on progress and considerable time elapsed before work was resumed.

Just what the future of the lighthouse and the island are, only time can tell. As of now the lighthouse continues to function much as it did

Thank You Ed Banke !! |

from its inception, the big Fresnel still doing its job. The Coast Guard has dismantled many of the former buildings that comprised the station, and visitors to the island are extremely few. It is generally considered off limits to the public unless one is escorted by Coast Guard personnel, but it is readily viewed from a section of Coast

Highway 101, or from the commercial fishing craft that work the bountiful waters lying Off the island. The Coast Guard has from time to time given serious consideration to closing down the facility as an economy measure. In 1963, it was proceeding with plans to do just that, but the maritime industry strenuously objected and the agency relented.

When the light was first illuminated on December 31, 1891 it was a Happy New Year for mariners. Principal keeper was Christian Zauner, and he and his assistants put in considerable time supplying fuel to the boilers to get up a head of steam for the fog signal. Four keepers were usually in attendance, some of whom had their wives and children present. Sometimes their offspring had to get room and board on the mainland during their school years, and on other occasions the wives became the school mistresses on th e island Frequently, when the sea had a calm spell, off-duty keepers would use the station dory to go out fishing for additional morsels for the lighthouse menu.

Destruction Island, since resident personnel departed, has become somewhat like a ghostly plot in the ocean. The lawn is no longer mowed and weeds have grown up along all the cement walkways. The buildings not torn down are boarded up and the tramway rails are red with rust. The horn-billed auklets are back in large numbers living in harmony with the gulls, and the bracken and salmon berries are growing. Except for the buildings, it is almost like it was when the natives paddled out in ancient times to plant potatoes, gather berries, collect bird eggs and feast on mussels-almost as though time has stood still.

The lighthouse chores of scraping metal, applying red lead and white paint, cleaning glass prisms, polishing brass, hand wiping the five-wick lamp or packing coal oil up the spiral staircase to the watch room are only fragile memories of the past. The tenantless sentinel struggles on toward the century mark, its light and foghorn operating automatically, almost as if ghostly hands were in control.

From the Book: "Lighthouses of the Pacific"