Cape Hatteras - $$4.95

The southern coast, especially from Cape Hatteras southward, had a navigational problem peculiar to it: namely, the Gulf Stream. Coming out of the Caribbean, the stream rounds the end of Florida and courses northward to the vicinity of Cape Hatteras in North Carolina. The sound of ocean waves, the starry night sky, or the calm of the salt marshes, you can experience it all. Shaped by the forces of water, wind, and storms these islands are ever changing. The plants, wildlife, and people who live here adapt continually. Whether you are walking on the beach, kayaking on the sound, or climbing the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse there is something for everyone to explore!

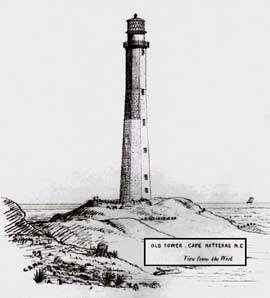

Cape Hatteras Lighthouse (1803)

The southern coast, especially from Cape Hatteras southward, had a navigational problem peculiar to it: namely, the Gulf Stream. Coming out of the Caribbean, the stream rounds the end of Florida and courses northward to the vicinity of Cape Hatteras in North Carolina. Here the stream apparently goes beneath the water and surfaces occasionally in unpredictable places. That it remains an entity north of Hatteras there is no doubt, for several northern ports that one would normally expect to be closed during the winter in view of their latitude remain open year around because of the warmth brought by the Gulf Stream. Murmansk in Russia is an example of an ice-free port, thanks to the Gulf Stream.

Cape Hatteras Lighthouse

As the Gulf Stream passes along the coast of the southern United

States it is well defined in its width, a fact known to Benjamin

Franklin; indeed, a 1770 chart of the stream is attributed to

Franklin. This 11 river in the sea," as it has been termed,

is almost as sharply defined as any river whose width is controlled

by banks of earth. Spaniards soon found that the stream could

speed their treasure-laden ships bound from the Caribbean to Spain.

Their ships followed the Gulf Stream out of the "Spanish

lake" and continued northward along the coast of Florida.

as they called the mass of land north of Cuba, to about Cape Hatteras

where they jumped off for Spain.

As the Gulf Stream passes along the coast of the southern United

States it is well defined in its width, a fact known to Benjamin

Franklin; indeed, a 1770 chart of the stream is attributed to

Franklin. This 11 river in the sea," as it has been termed,

is almost as sharply defined as any river whose width is controlled

by banks of earth. Spaniards soon found that the stream could

speed their treasure-laden ships bound from the Caribbean to Spain.

Their ships followed the Gulf Stream out of the "Spanish

lake" and continued northward along the coast of Florida.

as they called the mass of land north of Cuba, to about Cape Hatteras

where they jumped off for Spain.

The stream does not hug the shore of the southern states but rather is kept off-shore by a south-flowing cold stream called the Labrador Current. American seamen engaged in the coastal trade followed the Labrador Current when south-bound and the Gulf Stream when headed north. A vessel pointed southward could lose much time attempting to buck the swift Gulf Stream, which at times flows as rapidly as four knots. Moreover, getting into the Gulf stream under certain conditions could be unnerving. One nineteenth-century skipper of a coasting schooner described his experience:

"Had a good run to Cape Hatteras. Here a heavy northwester hit me and blowed my spanker away It blew a heavy gale and began to freeze tee ropes hard, And for the want of after sail I could not hold the beach and I drifted ever so far offshore into the Gulf Stream. This cold air on this warm water made the ghostliest sight I ever laid my eyes on before. For miles, before getting into the warm water of the Stream, it would seem I saw thousands of water spouts. Then it would look like forestry. This would pass off for a minute. Then next I would see some great city and to Maryland to the Florida Keys.

To be honest I felt scared. After a while I drifted out of the cold water into the warm water and then I was enclosed into this vapor and I could see nothing but cities, towns, forestry, and ships of all kind of rigs. And this was all vapor rising off of this warm water. Sometimes the sailors would squeal out, "There is a ship on the port." I would jump forward to get the bearing of her and about that time she would disappear [sic] and roll away as nothing but mist. Now I was lying right in the track of ships from New York or Philadelphia bound south. All that night I never shut my eyes in sleep and none of the crew got much. I expected every moment to be runed [sic] over. All day the next day, the wind continuing to blow a gale from the northwest, we continued to see these phantom ships, cities, forestry and water spouts. I was hove to all this time drifting to north and east."

The

most dangerous place along the southern coast was Cape Hatteras.

Here, a rocky, shallow finger known as Diamond Shoals extended

out from the cape about eight miles, thus leaving only a narrow

path a few miles wide that southbound vessels could follow in

getting past Cape Hatteras. A course too much to port put the

vessel into the counter-running Gulf Stream; too much to starboard

piled the ship on the shoals. Consequently, from the beginning

the desire was to put a lighthouse on the end of Diamond Shoals

where it could more effectively aid the mariner. But in reality

by the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when the

subject was first discussed, technology simply had not progressed

to an extent where man could successfully put a lighthouse on

such a wild and tempestuous spot. Therefore, Congress had no choice

but to put the lighthouse they proposed in the 1700s on land at

Cape Hatteras.

The

most dangerous place along the southern coast was Cape Hatteras.

Here, a rocky, shallow finger known as Diamond Shoals extended

out from the cape about eight miles, thus leaving only a narrow

path a few miles wide that southbound vessels could follow in

getting past Cape Hatteras. A course too much to port put the

vessel into the counter-running Gulf Stream; too much to starboard

piled the ship on the shoals. Consequently, from the beginning

the desire was to put a lighthouse on the end of Diamond Shoals

where it could more effectively aid the mariner. But in reality

by the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when the

subject was first discussed, technology simply had not progressed

to an extent where man could successfully put a lighthouse on

such a wild and tempestuous spot. Therefore, Congress had no choice

but to put the lighthouse they proposed in the 1700s on land at

Cape Hatteras.

The date of the establishment of the Cape Hatteras lighthouse is given by most sources, including the usually reliable Coast Guard Light List, as 1798. But the lighthouse was not established until 1803. Congress authorized the lighthouse at Cape Hatteras in 1794, but difficulties over obtaining the land and securing a contractor to build the structure resulted in construction not starting until late 1799.

The contractor was Henry Dearborn, former congressman later to become secretary of war, collector of customs in Boston, senior major general of the army, minister to Portugal, and the one for whom the well-known Michigan city was named. In addition to the Cape Hatteras light, Dearborn's contract called for him to build the Ocracoke beacon about forty miles to the southward.

Construction was slow, due primarily to Dearborn's workmen being hard hit by sickness during the summers. Illness, probably malaria, was to be a factor in the building of many of the southern lighthouses. Finally, however, Dearborn completed his contract in August, 1802, but for some reason the lighting of the tower did not take place until some time between June 28 and October 29, 1803.

This tower, with its light ninety-five feet above the sea, suffered the usual vicissitudes of weather and bad the normal upkeep and repair. It experienced at least one fire in the lantern, and the fifth auditor received a number of complaints through the years about the quality of the light. When the Lighthouse Board investigated the country's lighthouses in 1851, the members found the reputation of the Cape Hatteras light among navigators to be poor. The board concluded that "no single light on the coast" required improvement more than Cape Hatteras. The board felt the tower should be raised and a first-class illuminating apparatus put on it, since "there is perhaps no light on the entire coast of the United States of greater value to the commerce and navigation of the country . . . ...

In 1854, the Lighthouse Board raised the tower so that the

focal plane of the light from the new first-order lens was 150

feet ahove

sea level. The light could now be seen twenty miles at sea, well

beyond the end of Diamond Shoals.

In 1854, the Lighthouse Board raised the tower so that the

focal plane of the light from the new first-order lens was 150

feet ahove

sea level. The light could now be seen twenty miles at sea, well

beyond the end of Diamond Shoals.

At the beginning of the Civil War, the rebels removed the lens from the tower, but they did no damage to the structure. Playing a role as a rendezvous point during the struggle for military control of the Outer Banks of North Carolina, the tower remained unlighted until the federal troops had driven the Confederates from the banks. The Lighthouse Board used a second-order lens when it relighted the tower in June, 1862, but in 1863 it installed one of the improved first-order lenses on the tower.

By the end of the war the Lighthouse Board, upon recommendation of the district engineer, decided that Cape Hatteras needed a new tower, since the old one was beyond repair. In 1867, Congress appropriated the necessary funds, and in 1868, construction began on a new brick tower to be thirty feet taller than its predecessor and situated 600 feet northeast of the old tower. Various problems plagued the builders, including the sickness that had caused the workers on the original tower so much trouble. An army doctor sent to find a solution recommended giving each man a daily issue of one and a half ounces of whiskey and five grains of quinine as a preventative.

Despite these problems construction proceeded well, and on

September 17, 1870, the keeper lighted the lamp in the new first-order

lens. The light was 190 feet above mean low water. The district

lampist removed the lens and lantern from the old tower, and,

since there was danger it might topple in a storm, the district

engineer set off in the tower three charges of explosives, "blowing

out," be reported, a large wedge on the side toward the beach

& this old land mark was spread out on the beach a mass of

ruins."

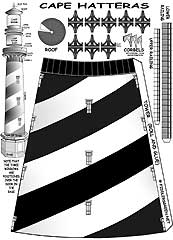

The new tower functioned well. To make it a better day mark the Lighthouse Board in 1873 had the tower painted with black and white spiral stripes.

At about the end of World War I erosion began to threaten the tower. Efforts through the 1920's and into the 1930's to halt the incursion of the sea were of little avail, and in 1936 the Lighthouse Bureau erected a new skeleton tower safely away from the marauding sea and moved the Cape Hatteras light to that point. The bureau then turned over the light station to the National Park Service to be included in Cape Hatteras National Seashore. In time the erosion threat eased, and in 1950 the Coast Guard made arrangements with the Park Service to re-exhibit the light in the old brick tower. Today visitors to the national seashore can visit the old station, view the maritime museum the National Park Service has created in the large keeper's dwelling, and, if in good physical shape, climb what was, and still may be, the tallest brick light tower in the world for a fine panorama of the Outer Banks, the sounds, and the Atlantic Ocean. The visitor, however, cannot go into the lantern where the lens, now automatic, is located.

Fittingly, this old tower, considered by the Lighthouse Board

and others during the nineteenth century to be the most important

light on the Atlantic Coast, is the national seashore's symbol.