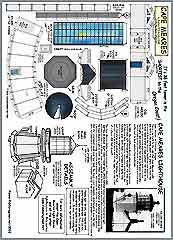

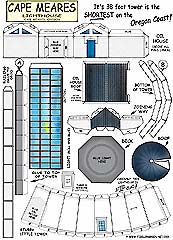

Cape Meares OR - $$4.95

Cape Meares Lighthouse was built in 1890 on the outer edge of a high, bold headland just south of Tillamook Bay. The Cape was named after Captain John Meares who first charted it in 1788 and was deemed as ideal site for a lighthouse. Easily seen from the sea, the outer point is below the fog line making the light visable during conditions when it's most needed.

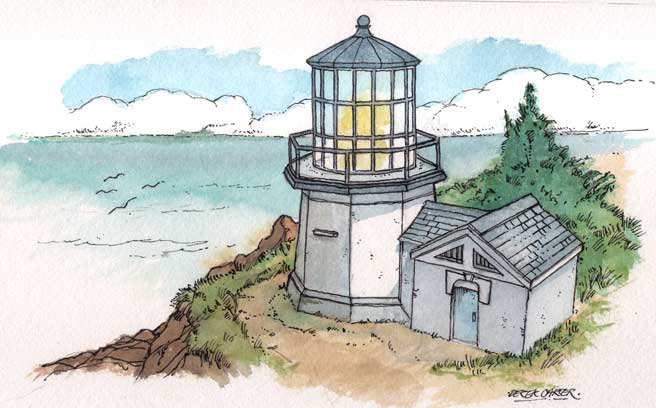

The Cape Meares Lighthouse, Cape Meares, Oregon

Cape Meares Lighthouse was built in 1890 on the outer edge of a high, bold headland just south of Tillamook Bay. The Cape was named after Captain John Meares who first charted it in 1788 and was deemed as ideal site for a lighthouse. Easily seen from the sea, the outer point is below the fog line making the light visible during conditions when it's most needed.

The 38-foot tower is the shortest on the Oregon coast and stands 217 feet above the water on near vertical cliffs. In 1963 the original first-order Fresnel lens was de-commissioned and replaced with an automatic beacon in 1963. Visitors today can view the lighthouse by taking a leisurely stroll through a corridor of trees down to the lighthouse.

The 38-foot tower is the shortest on the Oregon coast and stands 217 feet above the water on near vertical cliffs. In 1963 the original first-order Fresnel lens was de-commissioned and replaced with an automatic beacon in 1963. Visitors today can view the lighthouse by taking a leisurely stroll through a corridor of trees down to the lighthouse.

After being retired and neglected for a few years, the original workroom was dismantled and there was talk of doing away with the lighthouse as well. Public outcry was heard, and between the Friends of Cape Meares and the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department (OPRD) the lighthouse was saved. Now it's one of the prime attractions on the Three Capes Loop.

Even with a public outcry, it took the cooperation of more than one group to save Cape Meares Lighthouse. And that's the case with many of the lighthouses along the Oregon Coast.

Cape Meares Lighthouse, (1890)

Cape Meares, near Tillamook, Oregon

There's no truth to the tale that Cape Meares Light was built in the wrong place. For years, the story has circulated that the compact lighthouse was supposed to have been located at Cape Lookout, ten miles to the south. A government engineer scouted both locations thoroughly and concluded that while both were desirable, loftier Cape Lookout would make a far more difficult and costly spot to land construction materials.

In 1886, the Lighthouse Board asked Congress to approve a first-class light station at Cape Meares, five miles south of Tillamook Bay. Responsive lawmakers voted funds the following year. With them, a Portland iron works firm constructed an octagonal brick tower sheathed with cast-iron plates and painted white. The sloping, 38-foot sentinel stood at the west end of the cape, near the brink of a steep, 216 -foot drop off.

The Cape Meares station began service on 1 January 1890, sporting

an unusual, eight-sided Fresnel optic, whose bullseye lenses focused

a fixed white light, interspersed with a red flash, from a height

of 223 feet above the ocean.

Electricity began powering the Cape Meares Light in 1934. In April 1963, the Coast Guard installed an automated aero beacon atop a nearby concrete building, removed the keepers, and closed the station. A year later, news spread that the government would soon tear down the tower. Local residents, determined to save the light, were instrumental in having it leased to Tillamook County. Four years later, the property was turned over to the Oregon Parks and Recreation Dept, which removed deteriorated buildings, landscaped the grounds and, in 1980, opened the popular spot to the public.

Viewing spot: On site, Cape Meares State Scenic Viewpoint

Directions: From US 101, in Tillamook, turn west onto Third St (which becomes Netarts Rd beyond the city limits) and proceed 1.75 miles. After crossing the Tillamook River bear right onto Bayocean road to Cape Meares Lake.. Turn left and follow the signs.

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A LIGHTHOUSE KEEPER....

Cape Meares lighthouse was tended by three keepers: an appointed keeper and a first and second assistant. The main tasks were to keep the light burning from sunset to sunrise and to maintain the equipment. Among the daily tasks done by the keeper and his first assistant were to :

Clean and polish the lenses to prevent pitting by spray, trim or replace the large wicks, filter the kerosene and fill the lamp..

Kerosene was strained many time using fine

silk for the final filtering. The second assistant swept, dusted,

and cleaned the inside of the buildings. Keepers wore linen aprons

to avoid scratching the lens with their coarse clothing.

The French hand ground Fresnel lens at Cape Meares is one of the only two eight sided lights in the United States- the other is in Hawaii. Keepers were given detailed instructions for maintaining the masterpiece..

Shaped like a giant beehive , the outer surface of the lens

is made of prisms, that bend the light into a narrow beam. The

beam is then passes through a magnifying glass, or bull's eye

at the center of each side that intensifies it, producing a brilliant

sheet of light that's visible for 21 miles.

Shaped like a giant beehive , the outer surface of the lens

is made of prisms, that bend the light into a narrow beam. The

beam is then passes through a magnifying glass, or bull's eye

at the center of each side that intensifies it, producing a brilliant

sheet of light that's visible for 21 miles.

The original light was a heavy bronze five-wick kerosene lantern that was turned by weights and pulleys. Four sides of this 8-sided lens were covered with red glass, which produced an alternating red and white beams as the light turned. Cape Meares light of of the "first order'..the largest of seven lens sizes.

The Cape Meares Lighthouse, a short, stout tower, is anchored

to the outer edge of a high, bold headland just south of Tillamook

Bay. The seaward face of Cape Meares is cut by near-vertical cliffs,

and at the point where the tower stands, the cliffs drop nearly

216 feet to the waves below. Established in 1890, the tower is

all that remains of the original lighthouse station.

Visitors to the lighthouse park their cars in the place once occupied by the keepers' dwelling, a barn, and gardens. From the parking lot, a long, straight path leads down through a corridor of trees to the lighthouse. Though the tower's base is hidden from view, the lantern room, framed by trees, looms large with its original first-order Fresnel lens inside. This is the same path the keepers used to tend the light. When gale winds blew, they had to crawl, for then there were no trees to buffer the wind.

Like the Yaquina Head Lighthouse, the Cape Meares Lighthouse has been plagued with the rumor that it was built in the wrong place. As the rumor goes, the tower should have been built on Cape Lookout, ten miles to the south. Records, however, show that the lighthouse was built at the location designated by the Lighthouse Board.

In January 1886 a bill was introduced in Congress to build a first-order light at Cape Meares. Before the bill was passed, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers sent J. P. Polhemus to examine Cape Meares and Cape Lookout for a lighthouse site. Polhemus spent several days in May on both capes, hiking old Indian and bear trails. He camped out, taking measurements and compass bearings. To measure the height of Cape Meares, he dropped a marked cord down the cliff.

Polhemus reported that Cape Lookout "presents a very salient point for a Light House, and it more nearly divides the distance between the Light Houses on Tillamook Rk [sic] and at Cape Foulweather [Yaquina Head].... " A lighthouse at Cape Lookout, however, would be higher than desirable, and it would be difficult to get building materials there.

"Cape Meares," Polhemus continued, " . . . affords nearly as good a site as far as the view from sea is concerned, and being lower gives a better situation of light with references to fog." Cape Meares also had a fresh water supply from a spring and easier access for delivering building materials.

In March 1887 Congress passed the bill to build a lighthouse on Cape Meares. A wagon road was built from the bay to the site, and construction began in the spring of 1889. Charles B. Duhrkoop, one of the contractors, built the tower's octagonal exterior walls with sheet iron made in Portland. The inside walls were lined with bricks made and fired on the site. By September the thirty-eight-foot-tall tower was completed.

A first-order Fresnel lens, made in France, was shipped to the cape in crates. It was assembled in the tower by matching the numbers inscribed on the brass frames of each section.

By late November, three men-Anthony Miller, principal keeper, and his two assistants, Andrew Hald and Henry York-had moved into the two new dwellings. On January 1, 1890, they wound the clockwork mechanism to rotate the lens, and they lit the five-wick kerosene lamp. The eight-paneled lens, including four with bullseyes and red screens, began to turn slowly. (Bullseyes are circular, convex lenses.) The lens exhibited a fixed white light, with a red flash every minute, that could be seen for twenty-one miles. There was no fog signal at the station.

Second assistant York was the only married man on the station. When he was settled, he sent for his wife and two children, ten-year-old Mabel and her three-year-old brother. The family left Portland for a three-day journey with a sewing machine, trunks, and crates packed with household goods. They traveled by steamer to Astoria, and the next day boarded a small schooner bound for Tillamook Bay.

York had alerted Indians living on the bay's shores to watch for them. When the family arrived, the Indians helped them come ashore and put them up for the night. The next morning the sewing machine, trunks, and crates were loaded on a flat sled and pulled up the steep, muddy road by four oxen. Mabel rode on one horse, her mother and brother on another.

Not all the outside work was completed when the family arrived. For several months they trudged about in mud and dirt until wooden walkways were built around the dwellings and down to the tower.

In a 1963 newspaper article, Mabel reminisced about her days at Cape Meares. She said she often accompanied her father to the tower and stayed with him during his watch. "I sat in a big chair reading a big book as we watched the clock [clockwork mechanism]." During the day, she watched him polish the lens' prisms, each one "shining like a diamond." One day while she was walking to the tower, gale winds flipped Mabel over. She grabbed a wood stake to keep from being blown over the cliff and clung to it until her father rescued her. Much as Mabel and her family enjoyed life at the lighthouse, they left after only one year. There were no schools nearby, and they moved so Mabel could continue her formal education.

Transportation was another problem. At that time the only route

from the isolated station to Tillamook was down the muddy road

on the north side of the cape, then up the bay by boat. Keepers

timed their trips to town with the tides. At high tide, they could

row the boat. At low tide, they had to pole the boat around mud

flats.

This route, however, was an inadequate way to haul heavy materials from Tillamook for ongoing building projects. By 1894 a wagon road was built down the south side of the cape, then inland, where it connected with county roads. Now the keepers had a choice of routes: one timed by the tides or a seven-hour ride by buckboard.

In 1895 a badly needed brick workroom was built at the base of the tower. Workrooms added comfort to a keeper's watch, especially on cold winter nights. There was a desk, a chair, and a wood stove which kept the keepers warm and the tower's interior dry.

During the next decade, life at the lighthouse station mirrored life in town, complete with a wedding, births, schooling, and a funeral.

George Hunt and his wife and children moved to Cape Meares when he was assigned principal keeper in January 1892. Several men assisted Hunt during the 1890s before George H. Higgins was appointed second assistant keeper in January 1901.

Higgins, a dapper young bachelor, wore a mustache and his dark hair parted in the middle. During his first year at the station, he courted Amelia M. Freeman, the daughter of a Tillamook pioneer family. On Christmas Day 1901, the couple was married at the lighthouse station. A photo displayed in the tower shows Amelia wearing a white wedding gown and George in his Lighthouse Service uniform with a white shirt and tie.

In the spring of 1903 Higgins, then a proud new father, was promoted to first assistant keeper. Two months later keeper Hunt became ill. On July 7, 1903, the lighthouse log entry read, "Attended to regular duties. Keeper sick with pneumonia." The entry was repeated each day until July 10, when a new entry read, "Commenced haying. Keeper died at 6 p.m." Hunt's funeral was held in Tillamook two days later. His widow served as acting principal keeper until August 2: "Keeper wife, Mrs. and children left station today."

The new principal keeper, Harry Mahler, arrived with his wife and three children a few days later. Mahler, mid-way in his forty-two-year career in the Lighthouse Service, had been transferred from Patos Island Lighthouse in Washington's San Juan Islands.

When the Mahlers arrived, there was a one-room schoolhouse about a mile away. The Mahler children and the assistant keeper's two daughters attended school during the summer months. With lunch buckets in hand, the five children rode two horses to school.

When Mahler left in 1907, Higgins was promoted to principal keeper, and then resigned two years later. He, his wife, and three daughters-all born at the lighthouse station-moved to Portland where Higgins entered the real estate business.

Only minor changes came to the station during the following years. In 1910 the original heavy bronze lamp was replaced by an oil vapor lamp. This eliminated the daily chore of trimming the wicks, but not the chore of winding the clockwork machinery. About every four hours the keeper on watch had to crank up the heavy weights by hand. If the mechanism failed, the keeper turned the lens by hand until morning, when repairs could be made.

The keepers' work was made easier in 1934 when two generators were installed to provide electricity to the tower. An electric light replaced the oil vapor lamp, and an electric motor rotated the lens. The two small buildings where oil for the lamp had been stored were torn down.

Cape Meares was one of the first Oregon lighthouses automated on the coast. A small concrete building holding a modern optic was built on the ledge above the tower. Then the original lens was decommissioned on April 1, 1963, and the new optic, flashing white, was switched on to operate twenty-four hours a day unattended.

The two Coast Guard keepers and their families moved away and the workroom was razed. When the Coast Guard was ready to raze the tower, local citizens rallied. They succeeded in saving the lens and tower and having the property leased to Tillamook County in 1964.