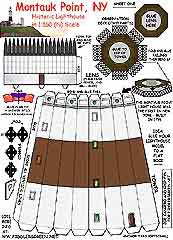

Montauk-Point, NY - $$5.50

Montauk is situated at the very end of Long Island, which juts straight out into the Atlantic Ocean for 175 miles. The Lighthouse was authorized by the Second Congress, under President George Washington in 1792. Construction began on June 7, 1796 and was completed on November 5, 1796. This 100 foot tower has been part of Long Island's land and seascape for over 200 years and still serves as an active aid to navigation.

Montauk Point, LI, NY Light House cardmodel

The Montauk Point Lighthouse, the oldest lighthouse in New York State

The Montauk Point Lighthouse, the oldest lighthouse in New York StateMontauk is situated at the very end of Long Island, which juts straight out into the Atlantic Ocean for 175 miles. The Lighthouse was authorized by the Second Congress, under President George Washington in 1792. Construction began on June 7, 1796 and was completed on November 5, 1796. This 100 foot tower has been part of Long Island's land and seascape for over 200 years and still serves as an active aid to navigation.

In 1797, John McComb, one of the United States' earliest famous builders and architects, and the son of a well-known builder and architect, completed the lighthouse at Montauk Point on the eastern tip of Long Island, New York. In compliance with his contract with the government, McComb erected an 80-foot tower of "Chatham freestone, fine hammered." The light was 160 feet above sea level. This tower has survived through the years, continuing to be ....

Chip, No problems. It downloaded just fine. By the way. You are really making it difficult for me :-) My wife loves lighthouses, so now I have to do these also. Maybe I can get her interested. Keep up the great work. Frank (3/31)

This is my first buy from Fiddlers Green. Just finished downloading, and its a little beauty.. if you're a fan of lighthouses like I am your going to love this new series...P.Crow (3/31)

Looks beautiful, Chip. Joe Cangero has done another stunning job. I especially like the additional buildings around the tower. Congratulations to Joe, and here's to the start sofa successful series. This is great news for the building section of Fiddler's Green. :-) David T. Okamura (3/31)

On Montauk Lighthouse:I found that a half ping pong ball fits nicely under the dome to give the strips something to hold onto whilest the glue (Alene's Tackey) is drying. Mike Banke

The Montauk Point Light House

In 1797, John McComb, one of the United States' earliest famous builders and architects, and the son of a well-known builder and architect, completed the lighthouse at Montauk Point on the eastern tip of Long Island, New York. In compliance with his contract with the government, McComb erected an 80-foot tower of "Chatham freestone, fine hammered." The light was 160 feet above sea level. This tower has survived through the years, continuing to be a significant mark to those vessels entering and leaving Long Island Sound. In the mid nineteenth century the Lighthouse Board called this station "a very important light, especially for navigators bound from Europe to New York." The Lighthouse Board greatly increased the effectiveness of the light in 1858 when it installed a first order Fresnel lens on the tower.

The Lighthouse Keeper

Members of the U.S. Lighthouse Service and the U.S. Coast Guard have been the residing keepers, tending the light for those at sea. Whaling ships, steamers, submarines, fishing and sailing vessels of all kinds have passed this tower on Turtle Hill, guided and reassured by its presence. On land, generations of visitors have made the trek to Long Island's easternmost tip, marveling at this lighthouse, the work of the keeper, and the beauty of Montauk Point.

Automated by the Coast Guard in 1987, the Montauk Point Lighthouse

no longer needs a light keeper; however, a keeper of its history

is essential. Under a program to provide for the continued maintenance

and preservation of this historic lighthouse, the Coast Guard

has transferred ownership of the lighthouse to the Montauk Historical

Society.

By George, It's Still Here

Built by President Washington in the aftermath of the Revolutionary

War, the Montauk

Lighthouse has withstood wind, time and tide

By George Dewan

Staff Writer

LEGEND HOLDS that even before there was a lighthouse, before the

white man came to claim the land, Montauk Indians would build

great fires at Montauk Point to call council meetings. And during

the Revolutionary War, when the British occupied Long Island for

seven years, the Royal Navy kept a huge fire burning at Turtle

Hill -- the Europeans' name for the bluffs that resembled the

carapace of a huge turtle -- as a signal beacon for their ships

that were blockading Long Island Sound.

Now there stands on Turtle Hill a 200-year-old lighthouse, almost as old as the nation itself. For two centuries, the Montauk Point Lighthouse has been a beacon for sailors navigating the treacherous waters that envelop the eastern end of Long Island. Sometimes the sea has won the battle, and the stories are legion of ships that have wrecked within range of the glaring beam.

The lighthouse was born in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War, when it became clear that safe coastal navigation was essential to the new nation's economic well-being. President George Washington agreed with Congress that a series of lighthouses along the Eastern Seaboard was a priority.

In 1795, Washington approved plans for a structure that would

rise 110 feet above the bluffs that mark the place where the eastern

edge of Long Island meets the sea at Montauk Point. Two hundred

years ago this Friday -- June 7, 1796 -- the first stone was laid

for what would be the first lighthouse built in New York State

and the fifth completed by the United States government.

In its lifetime, the lighthouse has progressed from smoky whale oil lamps to sophisticated modern lenses. Along the way, it has survived both nature's onslaughts and human neglect. The bluffs on which it stands have been chewed at by erosion, and the tower has been buffeted by gales and hurricanes. By the middle of the last century, the lighthouse had deteriorated so completely that it came close to being torn down.

Today, that would be unthinkable for the 110,000 visitors who

trek out to see one of Long Island's best-known landmarks every

year. Some

wear T-shirts that bear the inscription: ``Montauk -- The End.''

They walk the shell-and-stone-strewn beach, picnic in the adjacent

state park and look out into the Atlantic: The view from the end

of New York State is sublime.

And not just at night, when moonlight rides the ocean and the

lights of distant ships dot the dark. ``Summer at the lighthouse

is a time to arise

early to watch the sunrise,'' writes Marge Winski, who for the

past nine years has lived in an apartment where the keepers stayed

before the light was automated. Writing in the Montauk Historical

Society Beacon, Winski adds: ``Every morning is a spectacle as

the huge globe rises from the ocean's depths and turns the cliffs

lining Turtle Cove red with the first blush of light. For a brief

instant the sea is transformed into molten gold flowing toward

shore. As the waves break over the rocks everything becomes gilded

with liquid sunlight.''

The reasons that prompted the founding fathers to put a lighthouse on Montauk Point are explained by historic preservationist Robert J. Hefner. In an article for the Long Island Historical Journal, Hefner says: ``Perhaps its foremost appeal was as a landfall light for ships bound to New York from Europe. These vessels could take bearings from Montauk Point and use its light to conduct themselves from the Atlantic to safe anchorage northeast of Gardiner's Island, or in Gardiner's Bay. The light would guide ships on their way in or out of Long Island Sound, and those bound eastward in the Atlantic for Newport, New Bedford, and the Vineyard Sound. Also, Montauk Point was high enough to allow a tower to serve as a landmark within the Sound, especially to guide ships through the Race to New London and other mainland ports.''

John McComb Jr., a New York architect who had already built

a sturdy

lighthouse on Cape Henry in Virginia, was the low bidder for the

John McComb Jr., a New York architect who had already built

a sturdy

lighthouse on Cape Henry in Virginia, was the low bidder for the

project at $22,300. The federal government paid $250 for the 13-acre

site -- now reduced to three acres -- needed for construction

of the

lighthouse, a storage vault for whale oil for the lamp and a small

house for the keeper and his family, with room for livestock and

a garden.

Construction was completed in November, 1796, but the ship carrying

the initial supply of whale oil, caught in a violent storm, went

aground at Napeague Beach, 14 miles down the coast. The new lighthouse

was not lighted until the spring of 1797. Jacob Hand, the first

keeper, was hired at an annual salary of $266.66.

The original lighthouse, an octagonal, 80-foot tower made of

sandstone probably imported from Connecticut, had a base 28 feet

in diameter,

tapering to 16 1/2 feet at the summit. On top of the tower was

a 10-foot-high octagonal lantern room, glazed with storm panes.

Atop this was a large copper ventilator in the shape of a man's

head, used for venting the smoke. The first lighting device, set

in the middle of the lantern room, consisted of 13 whale oil lamps.

In 1838, each of the lamps was backed by a metal reflector. The

range of the light then was about 20 miles.

By the middle of the 19th Century, the lighthouse was falling apart, in large part because it had for years been poorly cared for. "The lamps and chandelier are in very bad order, the first showing decided marks of wilful abuse, or gross neglect,'' wrote inspector A. Ludlow Case in an 1854 report. "The lantern is dry -- but rain beats through under the deck in every storm, and runs in streams down the inside walls. The woodwork was wet and appeared to be rotten on the south, southeast and east faces.''

Inspector Case was back two years later and found the lighthouse ``in its usual untidy state,'' and the keeper nowhere to be seen. ``On his return he stated the reflectors had not been cleaned or the lamps put in their usual order as he had been obliged to go for a load of corn stalks to feed his cow.''

While the lighthouse may have been in disrepair, visitors,

especially paying visitors, became welcome guests, even though

the practice was

frowned upon by the federal Light-House Board. For a while, the

keepers kept a register in which visitors could make comments.

One entry reads: ``Epicurean Dinners served at Montauk. Bill of

Fare: October 17, 1854: Wild Goose, Broiled Chicken, Fried Oysters,

Raw Oysters.''

On Dec. 4, 1857, the Light-House Board wrote to the superintendent in Sag Harbor: ``This office is reliably informed that the keeper of the Montauk Point Light House repeatedly violated the instructions and regulations of the Department by entertaining boarders for pay in the dwelling house at that station and in vending intoxicating liquors on the government premises.'' The keeper was promptly dismissed.

Around this time, the government started replacing local keepers with career personnel. And a general program to upgrade all of the nation's lighthouses was begun. This included adding a lens designed by the French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel. Made up of a series of concentric glass rings, the new lens increased the intensity of the light so that it could be seen, in clear weather, at a distance of 53 miles. In addition, the Montauk station was changed so that its normally fixed light would be interrupted every two minutes by a brilliant flash of light.

This new flashing light, installed in 1858, almost immediately led to one of the worst maritime disasters in Long Island's history. The fixed-beam Shinnecock Lighthouse had just gone into operation at Ponquogue Point in Hampton Bays, about halfway between the Fire Island Lighthouse and the Montauk Lighthouse.

Ephraim Harding, captain of the full-rigged sailing ship ``John

Milton,'' did not know about the opening of the Shinnecock Lighthouse.

Nor did

he know that Montauk had switched to a flashing light. Returning

home in February, 1858, from a two-year voyage and heading for

New Bedford, the ``John Milton'' ran into gales and a heavy snowstorm

as it sailed east along Long Island's South Shore. When Captain

Harding

saw the steady beam of the Shinnecock Light on Feb. 20, he mistakenly

took it to be the Montauk light. Traveling a bit further east,

he turned to port and headed north, thinking he was heading into

the waters of Block Island Sound. Instead, the ``John Milton''

crashed into the rocky Long Island coast about five miles west

of Montauk Point. All 33 men aboard died.

In her memoirs, "An East Hampton Childhood,'' Mary Esther

Mulford Miller recalled being a 9-year-old girl at the time, and

going down to the shore with her father the next morning to see

the wreck. ``The morning saw a hopeless wreck piled on the rocks

five miles west of the

In her memoirs, "An East Hampton Childhood,'' Mary Esther

Mulford Miller recalled being a 9-year-old girl at the time, and

going down to the shore with her father the next morning to see

the wreck. ``The morning saw a hopeless wreck piled on the rocks

five miles west of the

lighthouse. Ship, masts, spars, sails, officers and crew lay in

a confused and frozen mass on the bleak beach.''

A number of other shipwrecks have occurred in the vicinity

of Montauk. Perhaps the worst happened on Sept. 1, 1951, when

the 42-foot fishing

excursion boat ``Pelican'' capsized in heavy seas just north of

the Point. Of the 64 people on board, 45 lost their lives.

Some maritime mishaps near Montauk Point have left their names on the maps. In 1862, the huge, double-hulled iron ship ``Great Eastern'' out of Liverpool, England, with 820 passengers aboard, scraped an underwater rock near Montauk that left an 86-foot-long gash in her outer hull. She limped into New York, but since then the culprit rock has been known to seafarers as Great Eastern Rock. And Culloden Point, near Great Pond Bay, was named for the British warship Culloden, which in 1781 was blown onto Shagwong Reef near Montauk. No lives were lost, but the ship was burned to the water line, and what remained now sleeps 15 feet under the water at Culloden Point.

One of the lighter Montauk shipwreck stories predated the lighthouse

-- it was told in 1794 by Mrs. Sarah Miller, a 78-year-old East

Hampton resident. She said she remembered the first tea kettle

ever seen in those parts, and it was taken off the wreck of the

``Captain Bell,'' which had gone aground on Montauk when she was

a young girl. All the farmers in the area came to look at the

tea kettle, but no one could figure out what it was. Finally,

one man said decisively that it must be the ship's lamp. The farmers

all agreed that yes, indeed, that's what it was -- the ship's

lamp.

Major storms were a huge problem at the lighthouse. Glass windows were constantly being blown out of the lantern, and sometimes just getting from the keeper's house at the bottom of the hill to the tower was a struggle. On April 5, 1799, Henry Dering, the superintendent of the lighthouse, wrote a letter to Tench Coxe, his superior in Washington:

``I have to inform you that a terrible tornado on Tuesday night ... accompanied with a violent wind and heavy storm of large hail broke more than half the glass of the lantern of the lighthouse ... The keeper ... was badly cut in the face and hands by the glass as it was drove in by the violence of the wind and hail.''

More changes came at the close of the 19th Century. A foghorn was permanently established in 1873, and although it has gone through many variations, its loudness has remained a constant. Earsplitting loudness. Margaret Buckridge Bock, whose father, Thomas Buckridge, was lighthouse keeper before World War II, remembers it well.

``I hear people talking about foggy weather,'' she wrote in a 1987 article in The Beacon. ``Nobody has any conception of fog unless they have lived at the Montauk Lighthouse. Sometimes, the fog engines would run steadily for a week to ten days. All the pictures on our walls would be crooked. When the horns finally stopped, it would feel as though the world had suddenly come to an end.''

The most conspicuous change as the century ended was a matter of paint. In 1900 the all-white lighthouse was given a horizontal brown band to distinguish it in daytime -- although it has been variously been described as ``red'' and ``maroon.'' The paint that is used today is Benjamin Moore's ``Van Dyke Brown.'' In addition, the original Fresnel lens was replaced in 1903 by a smaller -- but more powerful -- bivalve Fresnel lens (it looks like a clamshell) that flashed every 10 seconds. The original Fresnel had a range of 53 miles in clear weather; the replacement went to 64 miles.

Not long after the beginning of World War II, the lighthouse was made part of the Eastern Defense Shield guarding New York against possible invasion from Axis forces. Part of that shield, was Gun Battery 112 at adjacent Camp Hero. The two 16-inch guns are long gone, but the concrete structure that enclosed them is still visible, just a short walk down the beach.

Change came slowly to the lighthouse. Electricity and indoor plumbing weren't installed in the lighthouse and the keeper's dwelling until 1938. The rotation of the Fresnel lens was driven by a clockwork mechanism, and had to be wound -- like an alarm clock -- by hand every four hours. It was not until 1961 that an electric motor was installed, and the flashing pattern was reduced to five seconds.

At one point, the lighthouse seemed doomed. In 1968, continual erosion threatened to topple it into the sea. The Coast Guard revealed plans to close the lighthouse and replace it with an automated light on a steel tower a little farther inland. But two years later the plan was scuttled, in large part because of an all-out local effort to save the lighthouse, both from the wrecker's ball and two centuries of erosion.

The Coast Guard fully automated the lighthouse on Feb. 3, 1987, making the lighthouse-keeper's job obsolete. A new type of low-maintenance lens was installed, one which used a 1,000-watt bulb in front of a parabolic mirror, with a range of about 24 miles. The Coast Guard then leased the property to the Montauk Historical Society for 30 years. Although the beacon still flashes on top, the remainder of the lighthouse has become a museum.

The white tower with the brown stripe remains one of Long Island's special places.

The poet Walt Whitman knew this long ago. Here is what he wrote in his essay, ``Paumanok, and My Life on it as Child and Young Man,'' from ``Specimen Days'':

The designs for the 1860 renovation are entitled ''Montauk Light house as altered in 1860.'' Pasted on the drawing is a small paper inscribed ''Wm. F. Smith, Engineer Secretary Light-House Board''.

|

Captain William F. Smith's plans for the

Montauk Point Lighthouse transform it as closely as Focal Plane Elevation of 150'. The Light-House

Board required an elevation of 150' for first First Order Lantern. A first order lantern was

designed specifically to accommodate the radius Service Room and Watch Room. A service room below the lantern was required for the pedestal and revolving apparatus of the first order lens. Because the lamp of a Fresnel lens needed to be watched throughout the night, a watch-room was required for the keeper on duty. The easiest solution at Montauk Point was to set a standard assembly of service room, watch room, and balcony on top of the 1796 tower, Thus the height of the tower was increased in 1860 to provide a standard watch room and service room, not to provide a higher elevation for the first order lens. Fireproof Construction. The introduction of iron stairways, decks, windows, and doors by the Light-House Board probably had several goals: to make the towers more fireproof by eliminating wooden components; to allow a standard design to be manufactured in quantity and allow monitoring of quality; and to provide components ready for assembly to be shipped to remote locations. In 1860 the tower at Montauk Point was gutted of its wooden floors, stairs, and windows. A new spiral iron stairway was built in a new circular brick stairwell, The watch-room and service-room stairways were built up of standard iron units, iron decks, casement sash, and components in the renovated tower were installed, The only wooden components in the renovated tower were the interior main balcony doors. The renovation of the Montauk Point Light Station in 1860 involved more than the tower itself, Other elements of the Light-House Board's standard plan for the first order lighthouse were also introduced, An oil house containing a room for oil storage and a workroom for maintenance was built adjacent to the tower. A double keeper's dwelling was built to house the three keepers appointed to a first order lighthouse. And a passage connected the living and working areas of the station. |

Joe Cangero's Main Dwelling mock up |

Thank You Ed Banke !! |