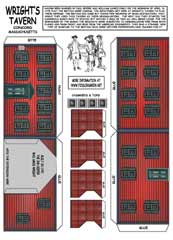

Wright's Tavern - $$4.95

April 19, 1775 dawned clear and cold. On the road from Boston to Lexington a British force, numbering between 700 and 800, marched on its way to Concord to "seize and destroy all the Artillery and Ammunition, Provision, Tents, and all other military stores you can find." They had been marching most of the night unobserved, they hoped.

Lexington Mass, New England - Wrights Tavern

April 19, 1775 dawned clear and cold. On the road from Boston to Lexington a British force, numbering between 700 and 800, marched on its way to Concord to "seize and destroy all the Artillery and Ammunition, Provision, Tents, and all other military stores you can find." They had been marching most of the night unobserved, they hoped.

April 19, 1775 dawned clear and cold. On the road from Boston to Lexington a British force, numbering between 700 and 800, marched on its way to Concord to "seize and destroy all the Artillery and Ammunition, Provision, Tents, and all other military stores you can find." They had been marching most of the night unobserved, they hoped.No sooner had they left Boston, however, than two couriers, Paul Revere, a silversmith by trade, and William Dawes, a young cordwainer and experienced express rider, mounted and rode hard for Lexington and Concord by different roads to sound the alarm that the British Regulars were coming to capture the supplies.

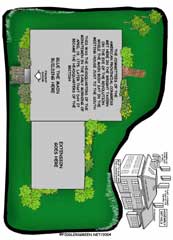

"The shot heard 'round the world" and Wrights Tavern

April 19, 1775 dawned clear and cold. On the road from Boston

to Lexington a British force, numbering between 700 and 800, marched

on its way to Concord to "seize and destroy all the Artillery

and Ammunition, Provision, Tents, and all other military stores

you can find." They had been marching most of the night unobserved,

they hoped.

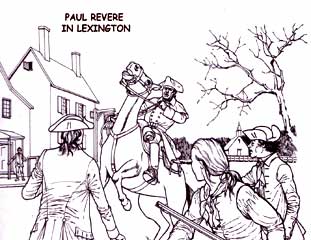

No sooner had they left Boston, however, than two couriers, Paul

Revere, a silversmith by trade, and William Dawes, a young cordwainer

and experienced express rider, mounted and rode hard for Lexington

and Concord by different roads to sound the alarm that the British

Regulars were coming to capture the  supplies. Revere reached Lexington

first and stopped to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock, two radical

leaders hiding out from the British, that if they stayed there

they probably would be captured as the soldiers marched through.

Shortly afterward Revere was captured by a British patrol, but

Dawes and Dr. Samuel Prescott, who had been courting a girl in

Lextington, continued on.

supplies. Revere reached Lexington

first and stopped to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock, two radical

leaders hiding out from the British, that if they stayed there

they probably would be captured as the soldiers marched through.

Shortly afterward Revere was captured by a British patrol, but

Dawes and Dr. Samuel Prescott, who had been courting a girl in

Lextington, continued on.

As the scarlet tip of the sun burst over the horizon, flushing

the cloudless sky, the advance guard of six companies of light

infantry commanded by Major John Pitcairn approached the small

village green in Lexington. On the green stood sixty or seventy

armed minutemen, farmers mostly and dressed as such, in two uneven

ranks, commanded by Captain John Parker. "let the troops

pass by," Parker ordered, "and don't molest them without

they begin first."

Pitcairn, a seasoned Marine veteran and patient, tactful Scotsman,

was relieved to see only a handful of armed men, but he could

not ignore them. If he continued his march on the Concord road

he would expose his right flank to the armed civilians, and he

was too good a soldier to take that risk. He ordered his six light

companies into line of battle and advanced across the green. Parker,

sensing the hopelessness of the situation and conscious of his

responsibility as company commander, ordered his men to disperse.

Some of them began to drift away.

Then "the shot heard 'round the world" was fired,

from where and b y

whom will probably never be known. Pitcairn, who had ordered his

troops not to fire unless fired upon, lost control of his men

temporarily. The Redcoats fired at the dispersing rebels and rushed

after them with the bayonet, despite Pitcairn's order to cease

fire. When the rising east wind cleared away the acrid smoke,

it revealed the green deserted except for the Redcoats and the

rebel casualties. Eight Massachusetts men had been killed and

two wounded; one British soldier and Pitcairn's horse had received

minor flesh wounds.

y

whom will probably never be known. Pitcairn, who had ordered his

troops not to fire unless fired upon, lost control of his men

temporarily. The Redcoats fired at the dispersing rebels and rushed

after them with the bayonet, despite Pitcairn's order to cease

fire. When the rising east wind cleared away the acrid smoke,

it revealed the green deserted except for the Redcoats and the

rebel casualties. Eight Massachusetts men had been killed and

two wounded; one British soldier and Pitcairn's horse had received

minor flesh wounds.

Who fired the first shot? All the minutemen denied that it came

from their ranks, but it must be remembered that it was to the

Americans' advantage to make it appear that the British had started

it. Pitcairn, an honest and efficient officer, reported that he

did not give the order to fire and did not believe his men fired

first. It is possible, of course, that one of his junior officers

or men might have fired without Pitcairn's knowledge. It is also

high possible that the first shot came from someone not on the

green at all, but hiding behind a wall or tree, or from the group

of spectators in front of the tavern on the green, or even, as

some maintained, from an upper window of White Tavern itself.

Whoever he was, he was certainly a poor marksman, which would

seem to rule out the men on the green who had the advantage of

point-blank range at the massed British troops.

Of more significance is the question of why Captain Parker and

his men were on the green in the first place. At midnight they

had agreed "not to be discovered nor meddle," but just

a few hours later they stood boldly exposed on the open green.

Parker, an experienced soldier, realized they were too few to

halt the British advance, b ut

if he had by any chance decided to make a stand he surely would

not have exposed his men in the open like that. He would have

placed them behind trees, fences, or houses, Indian style. Why,

then, this peculiar maneuver?

ut

if he had by any chance decided to make a stand he surely would

not have exposed his men in the open like that. He would have

placed them behind trees, fences, or houses, Indian style. Why,

then, this peculiar maneuver?

The finger of suspicion points to wily Sam Adams, the tireless

agitator and the dynamo who kept the revolutionary movement going

when the interest of others flagged. He believed that to "Put

your enemy in the wrong and keep him so, is a wise maxim in politics,

as well as in war." Organizer of the Boston Tea Party and

propagandist for the so-called Boston Massacre, Adams was adept

at practicing what he preached. "It must come to a quarrel

with Great Britain sooner or later," he wrote, "and

if so, what can be a better time than the present?"

At this time the American cause was not going well and the

rebel leaders believed that some dramatic incident was needed

to fan the flames, provided, of course, that the British could

be made to appear in the wrong. It would certainly seem logical,

then, and in character for Sam Adams to suggest to the Reverend

Jonas Clark, the undisputed political leader in Lexington, and

one whom Captain Parker would undoubtedly obey, that if the minutemen

were to appear armed on the green it might provoke the British

into making a mistake. In any event, Adams was not surprised at

what did occur. Fleeing in a carriage with Hancock when they heard

the Redcoat volley, Adams exclaimed, "Oh! What a glorious

morning is this," and few believe he was talking about the

weather.

The British immediately regrouped and continued to Concord. By

now the alarm had gone far and wide. Bells, guns, and drums called

out for the minutemen

and the militia. Express riders passed the word from town to town:

"To arms! To arms! The war has begun!" Men seized muskets

and powder horns and streamed toward Concord. Most of the military

stores had already been removed or hidden, but what was left was

now hastily taken to the woods, concealed in barrels and attics,

or buried in ploughed fields. When the British entered Concord

the Americans retreated to Punkatasset Hill, just west of the

North Bridge over the Concord River, and the Redcoats proceeded

to search the town, leaving only a small force at the bridge.

The number of rebels on the hill steadily increased - minutemen,

militia, and unorganized volunteers, old men and young boys. Soon

they were over 400 strong and becoming surly and impatient. Were

they going to stand there and let the Redcoats burn the town?

No. The order was given to march on the bridge. It was all over

in a few minutes, as the Redcoats retreated. The British had three

killed and nine wounded; the Americans, two killed and three wounded.

out for the minutemen

and the militia. Express riders passed the word from town to town:

"To arms! To arms! The war has begun!" Men seized muskets

and powder horns and streamed toward Concord. Most of the military

stores had already been removed or hidden, but what was left was

now hastily taken to the woods, concealed in barrels and attics,

or buried in ploughed fields. When the British entered Concord

the Americans retreated to Punkatasset Hill, just west of the

North Bridge over the Concord River, and the Redcoats proceeded

to search the town, leaving only a small force at the bridge.

The number of rebels on the hill steadily increased - minutemen,

militia, and unorganized volunteers, old men and young boys. Soon

they were over 400 strong and becoming surly and impatient. Were

they going to stand there and let the Redcoats burn the town?

No. The order was given to march on the bridge. It was all over

in a few minutes, as the Redcoats retreated. The British had three

killed and nine wounded; the Americans, two killed and three wounded.

Unable to locate any significant amount of military stores, the British force regrouped and a little later started the dangerous march back to Boston. For the first mile or so the long column was not molested. The all hell broke loose, and for the remainder of the march the Redcoats were subjected to a galling demoralizing fire from both flanks and front and rear. Only about 400 rebels had been in the fight at the bridge, but as the day wore on the number increased to several thousand. They would shoot at the enemy column from behind fences, trees, barns, walls, from inside houses, then reload, hurry ahead, and shoot again. This was a strange, new type of warfare to the British, who were neither experienced nor trained for it. To them it seemed dishonorable, hiding and shooting at men in the open who could not even see their enemies. As one Redcoat wrote his family; "They did not fight us like a regular army, only like savages."

But the column staggered on, the dead lay where they fell,

the wounded tried desperately to keep up, and by late afternoon

they were hungry, thirsty, exhausted, and almost out of ammunition.

No longer an orderly marching column, they were now just a mass

of men crowding the road. Soldiers located homes, shot the occupants,

and ransacked taverns for food and drink. A British officer admitted

"that we began to run rather then retreat in order . . .

the confusion increased rather than lessened."

With any organization and leadership at all, the Americans probably

could have destroyed or captured the entire British force. But

this was not an American army, it was merely an armed mob, angry

and vengeful, with each individual more or less on his own. There

was no order, direction, or control; no objective except for each

man to get a shot at the hated Redcoats. So the column was allowed

to reach Boston that night, having suffered about 273 casualties;

the revels about 95. And as the disordered American militia milled

about Cambridge that night, one of the wrote his wife, "Tis

uncertain when we shall return. . . . Let us be patient and remember

that it is in the hand of God."

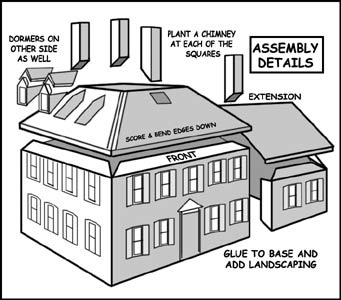

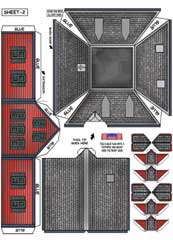

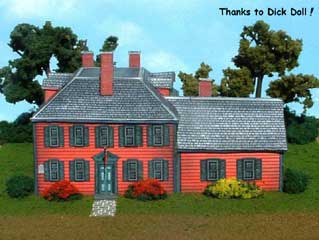

Thanks to Dick Doll for this beautiful diarama!