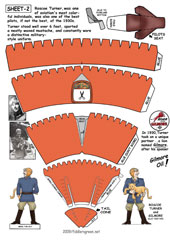

Lockheed Explorer - $$6.95

There was great hope for the Lockheed Explorer, with designs on Antarctic exploration, and Trans-Pacific flights. But alas, the Explorer model turned out to be the least successful of all Lockheed's great early planes. A total of four Explorers were built and all four crashed. Even tho it sure was a good looking 1920s airplane. A cartoon cutout model of Roscoe Turner (Google him :) and his lion mascot is included.

Lockheed Explorer Monoplane - Downloadable Cardmodel

There was great hope for the Lockheed Explorer, with designs on Antarctic exploration, and trans-Pacific flights.

But the Explorer was arguably the least successful of Lockheed's planes. A total of four were built.

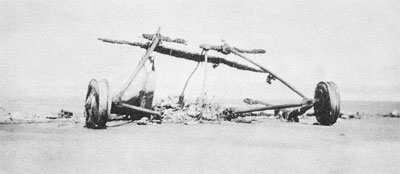

Of the four, three crashed and one was totally burned to the ground, only the landing gear survived.

Hi Chip! I just finished up your Lockheed Explorer. What a great model of a great plane! I built the larger version, and thought you might like to see some pictures. The rather curious streaking you see is the result of some experimental printing I did with a laser printer. Even with that it looks nice. Thanks for making this model available. Tim

The Ill Fated Explorer

The first Lockheed Explorer was commissioned by Sir Hubert Wilkins, for a new aircraft to be used for Antarctic exploration. The Explorer was named in honor of Sir Hubert. It was one of the last Lockheed planes designed by Jack Northrop before leaving Lockheed in 1928.

It was a revolutionary design, it was a Vega fuselage with a low-wing, single-float seaplane with retractable outrigger pontoons. But Wilkins decided to go with a standard high-winged Vega, with floats, as he would most likely be landing amid pack ice. This was not the death of the Explorer design.

John Buffelen, a Tacoma Washington lumber tycoon, and the Tacoma Chamber of Commerce, had a pilot. Lieutenant Albert Harold Bromley, with aspirations of world recognition, to be the first pilot to fly non-stop across the north Pacific. They searched all the West Coast aircraft factories, when they came upon the experimental "seaplane" the Lockheed Explorer. Bromley had made test flights with the Explorer in Burbank (home of the Lockheed factory) and was satisfied with the performance and flew it non-stop back to Tacoma.

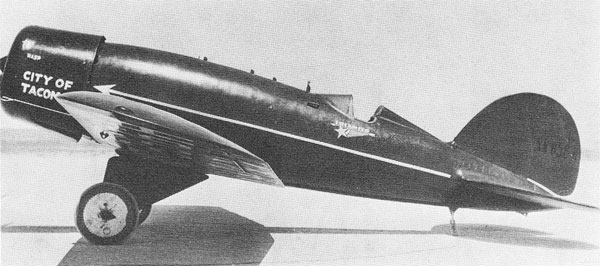

The plane was christened The City of Tacoma, and on July 28, 1929 she was ready for her attempt to fly to Tokyo, in front of 20,000 onlookers. Having filled the gas tanks, in the cool morning. The launch being late afternoon, due to expansion, gas began to spew out from the tank breathers covering the wind screen and obscuring the view. Bromley peered over the side of the windscreen only to have his  goggles covered in gasoline, in desperation he swept them off.

goggles covered in gasoline, in desperation he swept them off.

As the plane was heading down the runway the tail lightened, now being blinded by the gasoline, Bromley lost control of the Explorer and it ended up perched nose first into the ground. Thankfully there was no fire as the crowd of onlookers had rushed past the police and National Guardsmen and surrounded the wreckage. Bromley's aspirations were not dashed with this first failed attempt, "Nobody is to blame but myself," he said. "I can do it if they'll give me another chance."

John Buffelen and the Tacoma City of Commerce would not give up so easily either. They had the a new plane made but the new design had some issues. The tail rudder had some "fluttering". The new rudder came off in test flight and the test pilot Herb Fahy crashed and he suffered broken elbow and a few bruises.

Still undaunted and wanting to put Tacoma on the Pacific air map. Buffelen has a third Explorer built, this one looking more like a Sirius, but still having a lone cockpit. This one unfortunately did not have any more success getting off the ground than the first. She had barley lifted off the ground when she came crashing down and exploding in flames the test pilot Ben Catlin walked out of the flames a human torch. He died that evening. Shaken by the dismal chain of events, the Tacoma Chamber of commerce sought out a fourth and final plane from a different manufacturer.

This was not the end of the Explorer's story. A fourth Explorer was built, this one for Art Goebel, a rugged veteran of both the Dole Air Race and transcontinental record flights. Goebel had announced plans for a non-stop transcontinental record and a Paris-to-New York flight later in the summer. He named the blue and yellow ship Yankee Doodle, reminiscent of the previous Lockheed he'd flown to fame.

|

Roy Ammel with the Blue Flash before his non-stop flight from New York to Panama. |

Despite her capabilities, the Explorer did not satisfy the famous distance flyer, and he never took delivery. She went instead to the Pure Oil Company of Chicago, to be flown for advertising purposes. Repainted and rechristened Blue Flash, she was flown by a hired pilot, Captain Roy W. Ammel. Ammel flew the Blue Flash successfully in the first non-stop flight from New York to Panama on November 9-10, 1930, landing at France Field after a 24 hour flight.

But the return trip to Chicago brought disaster. Transferring to the longer, unfinished airfield at Ancon, Ammel found that the uneven terrain differed considerably from the concrete of Floyd Bennett Field back in New York; but he tried a take-off anyway. The Blue Flash skidded on a wet spot, dug her nose in the earth, and reared up to crash on her back. Luckily there was no fire, as Roy Ammel, was unconscious but not seriously injured, and had to be chopped out of the wreckage. Thus ended the ill fated Explorer, only to be heard of again when Wiley Post modified an Orion, with and Explorer wing, and floats. The terrible out come of that union cost both Wiley Post and Will Rogers their lives.

|

|

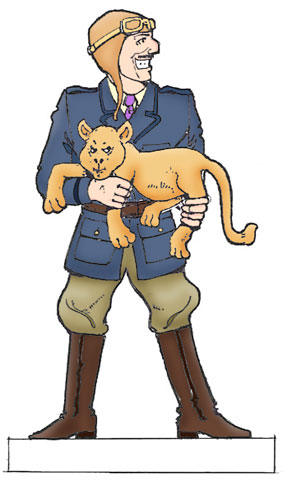

Roscoe Turner and Gilmore. |

This 2 sided Roscoe Turner Paper Doll comes free with the Lockheed Explorer model. |

The Full Story of the Explorer

Wilkins sent a tentative order from Europe for a second Lockheed airplane to be tested in the Antarctic. Before leaving the company in June 1928, Jack Northrop had proceeded with drawings and preliminary arrangements for the low-wing, single-float seaplane with retractable outrigger pontoons. This revolutionary design - one he'd started at the time Wilkins bought his Vega was now called the Explorer model in the flyer's honor. The fuselage was cut and work had begun before a final consultation between Sir Hubert and the designer brought out the possibility of landing amid pack ice. Therefore a high-winged monoplane would be preferable. The Explorer was temporarily shelved in favor of a regulation Vega joined by stilt like bracing to twin floats; thus it became the first seaplane in the wooden Lockheed series.

The enthusiasm for flying across the Atlantic was never matched by flyers who even idly contemplated a similar conquest of the North Pacific: the 4,500-mile trip over fog-shrouded and storm-lashed waters appealed to only a handful of hardy aviators. To stimulate interest, therefore, the air-minded Tokyo Asahi (Morning Sun News) offered a $25,000 prize for the first nonstop flight, either way, between Japan and America.

Airplanes were improving by 1929, but a single-engine ship capable of lifting the nearly 1,000 gallons of gasoline necessary to go the distance would have to be specially built. A Tokyo flight would also require some good solid financial backing; and, even in such boom times, the green stuff had to be carefully promoted. Fortunately an angel was available in the person of John Buffelen, a Tacoma, Washington, lumber tycoon who wanted to put his town on the Pacific air map.

Genial John Buffelen and the Tacoma Chamber of Commerce had a man to fly to Tokyo. All they needed was a suitable airplane.

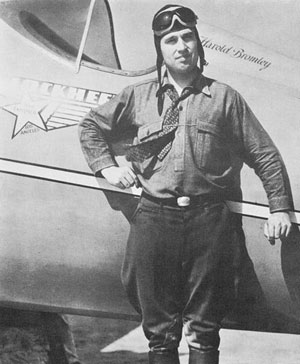

The pilot on whom the lumber city's committee

pinned their hopes for world recognition was

Lieutenant Albert Harold Bromley, a twenty-nine-

year-old Iowa flyer with Army training. Boyish,

taciturn Bromley had put up $2,000 of his own

money for the venture; with more cash assured,

he began to make the rounds of the West Coast's

aircraft factories.

The pilot on whom the lumber city's committee

pinned their hopes for world recognition was

Lieutenant Albert Harold Bromley, a twenty-nine-

year-old Iowa flyer with Army training. Boyish,

taciturn Bromley had put up $2,000 of his own

money for the venture; with more cash assured,

he began to make the rounds of the West Coast's

aircraft factories.

It was at the Lockheed plant in Burbank that the Lieutenant found the experimental "seaplane" which designer Jack Northrop had started for Hubert Wilkins. There had been little or no engineering done: it was merely a fuselage with the camber cut away to accommodate a lower wing. Bromley had to exercise considerable vision to see this dusty wooden shell as a finished airplane capable of flying him from Tacoma to Tokyo. But after talking to chief engineer Jerry Vultee, his enthusiasm was aroused, and he ordered the plane completed to his specifications for the long-distance attempt.

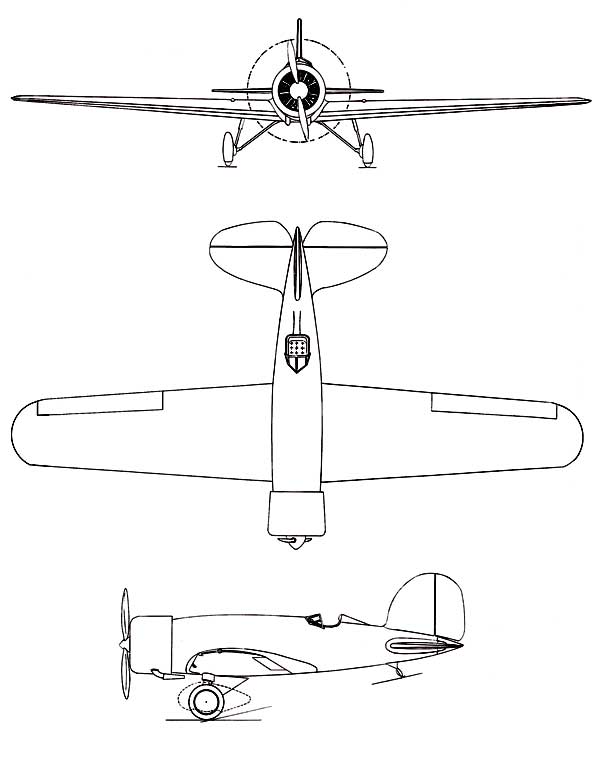

Within a few months Vultee and the factory crew had assembled the original Explorer model, Lockheed's first low-wing airplane. Its extra-long wing was broad and straight, with no dihedral angle-like the high wing of a Vega but at the base of the fuselage. A single cockpit, well to the rear, accommodated the pilot. The ship was painted the standard international orange.

Test-flying the special job was carried out from the long flat surfaces of Muroc Dry Lake, some sixty miles north of Burbank. On one run of nearly a mile, Lieutenant Bromley got off in the new monoplane with 8,500 pounds, an unofficial load record for the times. Jerry Vultee experimented during the tests with three types of vertical tail surfaces on the ship, settling on a compromise of rounded fin and squared-off rudder, used only on this particular airplane.

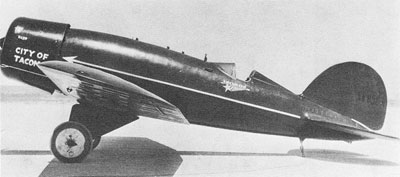

Satisfied with her performance, Bromley flew the big Explorer nonstop to Tacoma, where a special take-off ramp was being readied at Pierce County Airport. In the presence of 10,000 cheering onlookers the gleaming orange Lockheed was christened City of Tacoma by Clasina Madge Buffelen, the small daughter of the flight's backer. A tail wheel was substituted at the last moment for the conventional skid, to give the Explorer an even better chance of successful takeoff from the unpaved runway. With favorable weather predictions from the Aleutians and the Kuriles, and with plane and engine in the best possible shape, the chosen pilot was ready to start the longest over water flight ever attempted by man.

On Sunday, July 28, 1929, the City of Tacoma was poised atop the wooden ramp designed to give a boost to her take-off run. Harold Bromley, his goodbyes said, climbed in and listened carefully to the sweetly ticking Wasp ahead. The ship was in flying position, her tanks topped off full at 902 gallons. Gassing-up had already taken place-during the cool of the morning. It was this little overlooked detail that brought disaster.

As 20,000 onlookers quieted to watch, the Explorer rolled slowly down the ramp, gathering speed. At the bottom there was scarcely a jar, and Bromley thought that his last worry was over. Then a splatter of gasoline hit the windshield. With tail down, plus natural expansion, the fuel bubbled from the tank breathers atop the fuselage in a steady spray, fogging the view ahead. Building up speed, the pilot peered over to the side of the shield, only to have his goggles coat up with fuel. Desperately he brushed them back. A thousand feet further on the tail lightened at the 60-mph pace, but the stinging spray of gas was blinding Bromley. He could feel the ship wobble from the runway, swerving to the left. Then the right wheel crumpled on the rough ground, the wing followed, and in a moment the heavily loaded Lockheed was perched on her nose in a cloud of dust.

Harold Bromley leaped out as the ship careened to a stop. Gasoline gushed from the shattered wing and cracked fuselage. The massed and screaming spectators, converging on the wreckage, swept aside police, National Guardsmen, and a barbed wire fence. By some miracle there was no fire, and order was quickly restored. The Lieutenant, very low in spirits, did not offer any alibis. "Nobody is to blame but myself," he said. "I can do it if they'll give me another chance."

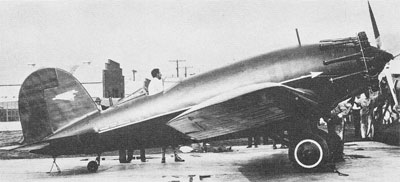

John Buffelen and the Tacoma committee assured the flyer that financing for a new airplane was certain. In Burbank the Lockheed factory worked like mad, and a new City of Tacoma was completed in a little more than six weeks. Innovations on the second version included droppable landing gear and a metal-sheathed belly skid along the bottom of the fuselage. Jerry Vultee was still experimenting with tail surfaces, and this Explorer was fitted with an overhung, counterbalanced rudder. With no wind tunnel, he had to "cut and try." Unfortunately, it was one of the talented designer's few bad guesses.

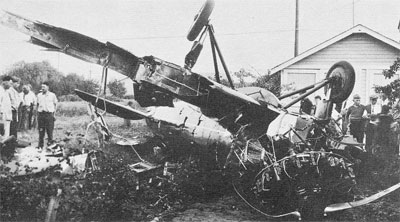

Test pilot Herb Fahy took the ship up for a trial hop on September 18, 1929, and quickly discovered a dangerous tail flutter. Three times he circled the Lockheed field at low altitude to show the engineers how it flapped. As they watched, the offending rudder whipped loose and fell practically at their feet, followed by the fin itself. Herb went into figure-eight contortions to control the uncontrollable. Off the east end of the runway the Explorer dipped under some wires, swished through the branches of a pepper tree, nicked the corner of a bungalow and came to inverted rest in a back yard. Fahy, lucky this time, crawled out with only a broken elbow and bruises.

Back at his drawing board Vultee had meanwhile designed the successful low-wing Sirius for Colonel Lindbergh. The third plane built for the Tacoma-Tokyo flight still retained the greater wingspread and single cockpit of the Explorer, but had a larger, Sirius-type fin and rudder. Two degrees of dihedral were given the wing for better flying characteristics. While waiting for his successive airplanes to be completed, Harold Bromley made ends meet with odd jobs of check-flying for Lockheed, and work piloting Vegas for Corporacion Aeronautica de Transportes, S. A., a Mexican airline that ran from El Paso to Mexico City and on down to Yucatan. Then in May 1930 the Pacific hopeful was back at Muroc Dry Lake for tests of the third City of Tacoma. Bromley did all the preliminary check flights himself. It looked like this Explorer was the plane in which he'd finally be heading for Tokyo. On thin financial ice, the Detroit-Lockheed management did not have the funds to cover Bromley's insurance for a full-load test. The crucial flight fell to their own new check pilot, big, friendly Hugh W. (Ben) Catlin, who was covered until May 25th.

At daylight on the day before the deadline the Explorer was readied with 900 gallons of gas in her tanks. Ben Catlin had to fly her, even when a leak in a gas tank delayed his take-off until the heat of the day. Harold Bromley drove to a pre- arranged position a mile down the shimmering lake bed: if the City was not off the ground by that point, the test pilot was to pull the dump valves. A mere half a mile ahead, the twelve-foot embankment of the Santa Fe Railroad angled across the long level expanse of Muroc.

Ben gunned the Lockheed and got rolling into the wind. Apparently riding a ground cushion, he whipped by Bromley's car with the tail wheel still touching, and resorted to bounce technique to clear by inches the railroad embankment on beyond. Floundering through the air, the City of Tacoma made a half-roll to land on her nose. The engine tore off on impact and the rest of the plane skidded on its back another hundred yards. Fire blazed around the hot exhaust stacks and licked up the trail of gasoline to the fuselage. Ben Catlin came walking out of the flames a human torch, only a hundred feet from the horrified Bromley rushing to the rescue. Whispering that he had been unable to reach down to trip the dump valves and mumbling apologies "for wrecking the ship," the test pilot died that evening.

Shaken by this dismal chain of events, the Tacoma Chamber of Commerce sought a fourth and final airplane for Lieutenant Bromley from another manufacturer, and any hopes of a Lockheed being the first plane to span the North Pacific appeared very dim indeed.

Built during the same period as Fierro's Anahuac was another low-wing Lockheed designed for the use of Art Goebel, the rugged veteran of both the Dole Race and transcontinental record flights. Art's plane was not a Sirius, but a single-cockpit Explorer like the planes built for Harold Bromley's proposed Pacific flights. Her eight tanks would hold 800 gallons of gasoline.

Goebel announced plans for an assault on the nonstop transcontinental record and a Paris-to-New York flight later in the summer. He named the blue-and-yellow ship Yankee Doodle, reminiscent of the previous Lockheed he'd flown to fame. Despite her capabilities, the Explorer did not satisfy the famous distance flyer, and he never took delivery. She went instead to the Pure Oil Company of Chicago, to be flown for advertising Purposes. Repainted and rechristened Blue Flash, the low-wing Lockheed was flown by a hired pilot, Captain Roy W. Ammel.

An ex-Army flyer and Chicago building materials broker, slight, balding Roy Ammel had kept drifting back to aviation after various business ventures. For his Pure Oil assignment the Captain went to California to take delivery of the big Explorer. Fire damaged the ship after a forced landing at Gila Bend, Arizona, and a crew from the factory under Don Young had to come out and disassemble it for shipment back to Burbank. It was September before Ammel and the Blue Flash reached New York, with plans for the first solo flight direct to Rome. Lockheed's ace troubleshooter Don Young was again retained by Pure Oil to speed Ammel on his way, and there was even some talk of stowing the curly-haired little mechanic in with the gas tanks. But the fall weather over the Atlantic did not co-operate, and after weeks of waiting Captain Ammel decided to make a lone visit to the Army base where he had once been stationed: France Field in the Canal Zone.

The first nonstop flight from New York to Panama came off on November 9-10, 1930. The Explorer loaded with 703 gallons of gas, Ammel got the ship off the runway at Floyd Bennett Field in 2,000 feet and headed south. He flew the blue plane by beacons, the sun, and dead reckoning all the way, fighting winds that kept blowing him off his course until he guessed he'd flown "about a thousand miles extra." Struggling to keep awake on the 24-hour-35-minute journey, the Captain sang to himself and lifted his seat to keep his head out in the slipstream. After the battery in the Blue Flash ran down, he read his instruments with a pocket flashlight. The leather flying suit which had seemed so snug and comfortable in New York nearly smothered Ammel as he approached the tropics. In the close confines of the cockpit he took nearly an hour to worm out of it. He was extremely happy to see the shores of Panama rise out of the Caribbean and to set the Explorer down on France Field.

A return flight to Chicago brought disaster. Transferring to the longer, unfinished airfield at Ancon, Ammel found that the uneven terrain differed considerably from the concrete of Floyd Bennett Field back in New York; but he tried a take-off anyway. The Blue Flash skidded on a wet spot, dug her nose in the earth, and reared up to crash on her back. Luckily there was no fire, for Roy Ammel, unconscious but not seriously injured, had to be chopped out of the wreckage. The New York-to-Panama hop was his one and only flying venture on a national scale.

|

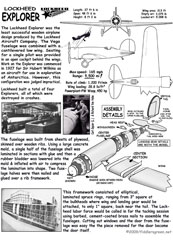

Length: 27 ft 6 in Wingspan: 48 ft 6 in Height: 8 ft 2 in Wing area: 313 ft Empty weight: 3,075 lb Loaded weight: 9,008 lb Max takeoff weight: lb Powerplant: 1× Pratt & Whitney Wasp, 450 hp Performance Max speed: 165 mph Range: 5,500 mi Rate of climb: 1,200 ft/min Wing loading: 28.8 lb/ft² |

The Lockheed Explorer, a high-wing monoplane from the late 1920s, was designed by Jack Northrop as a specialized variant of the Lockheed Vega for long-distance exploration. Built in 1929-1930, it featured a streamlined fuselage, cantilever wing, and powerful Pratt & Whitney Wasp engine, enabling extended ranges for polar and transoceanic flights. Famous aviator Wiley Post used an Explorer (named after Sir Hubert Wilkins) for a planned Alaska-to-Berlin flight in 1935, but it crashed shortly after takeoff near Point Barrow due to engine failure, tragically killing Post and humorist Will Rogers. Only a few were produced, with variants like the Sirius (used by Charles Lindbergh) sharing its innovative wooden construction and speed capabilities over 200 mph. The Explorer's legacy lies in advancing adventure aviation, though its production ended amid the Great Depression. Preserved examples, like a Vega variant at The Henry Ford Museum, showcase its role in Golden Age flying.

Before |

After |

|

|

|

|

|

|