Lockheed Vega - $$8.50

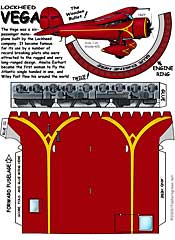

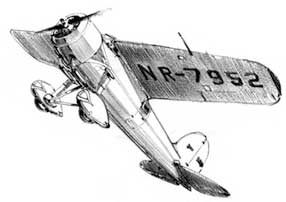

The Vega was a six-passenger monoplane built by the Lockheed company starting in 1927. It became famous for its use by a number of record breaking pilots who were attracted to the rugged and very long-ranged design. Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly the Atlantic single handed in one, and Wiley Post flew his around the world twice.

Lockheed Vega

|

|

Amelia Earhart's Lockheed Vega is shown flying into the rising sun on her solo flight across the Atlantic in 1932. |

|

The Fiddlersgreen downloadable Lockheed Vega model and the cute-as-a-button cutout of Amelia Earhart |

|

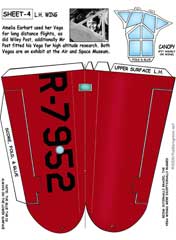

Amelia Earhart flew a Lockheed Vega 5B on many historic occasions including the 1929 first Women's Cross-Country Air Race (also known as the Powder Puff Derby), first female solo flight across the Atlantic, first female solo flight across the United States, and also set several women's speed and distance records. In its heyday the Vega 5B was known as a racing and record-setting aircraft and established a standard for many other transport aircraft.

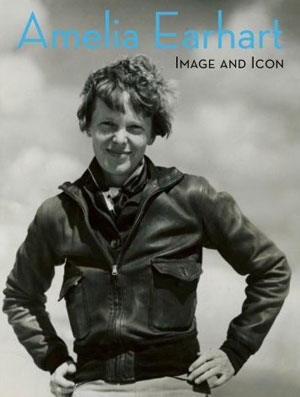

Earhart was born on July 24, 1897 in Atchison, Kansas. Earhart is perhaps best known for her mysterious disappearance which occurred somewhere near Howland Island in July 1937. The most extensive air and sea search in US Naval history was launched soon after and cost over $4 million. Amelia, her navigator Fred Noonan, and the plane, a Lockheed Electra, have never been found although there are dozens of theories as to what happened. Amelia's accomplishments include the first female to fly across the Atlantic (1928), first female to fly the Atlantic solo (1932), as well as several altitude and speed records. She was the first president of the Ninety-Nines, an organization created in 1929 to aid women pilots. The former tomboy was an advocate of women pursuing their dreams, particularly successful women in predominantly male-orientated fields.

Video about Amelia Earhart's Lockheed Vega |

What people say...

Nice job on the Vega. And thanks for including a proper engine for us. So how come so many of the planes of that era looked so fine? Now, if I could just find a good model of the Fairchild 24--with the inline engine! I think maybe I am the only modeler out here with a soft spot in the heart for that plane. Something to do with childhood....John

Lockheed Vega - Amelia Earhart and Wiley Post

Amelia Mary Earhart was born on July 24,1892 in Atchison,

Kansas. At the age of 10 she caught her first glimpse of an airplane at the Iowa State Fair.

A popular misconception is that this sparked a lifelong devotion to flight, but in fact it

was a further 10 years or more before Earhart began to develop a fascination with aviation.

Amelia Mary Earhart was born on July 24,1892 in Atchison,

Kansas. At the age of 10 she caught her first glimpse of an airplane at the Iowa State Fair.

A popular misconception is that this sparked a lifelong devotion to flight, but in fact it

was a further 10 years or more before Earhart began to develop a fascination with aviation.

After visiting her sister, who was studying at a Canadian college, she remained in Toronto and trained as a nurse before serving as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse in a military hospital until the end of World War I in November 1918.

Earhart next enrolled s a premed student at Columbia University in the fall of 1919. Yet some months later, at an air meeting in California, she took a 10-minute joyriding flight. "As soon as we left the ground I knew I myself had to fly!" she later reported. Soon after this she started to take flying lessons with one of the United States, pioneer women pilots, Anita Snook.

By October 1922, after gaining her 'wings," Earhart started to become involved in attempts to break flying records, her first success being a women's altitude record of 14,000 ft. She was also involved in the organization of the first Women's Air Derby race. During this race, Earhart was tied for first place with the great woman pilot Ruth Nichols at Columbus, Ohio, the event's penultimate intermediate landing point. Nichols crashed while trying to take off and Earhart, awaiting her turn to take of, jumped out of her machine and dragged Nichols, badly shaken but without any injury, from the cockpit of her wrecked airplane. Only then returning to her own airplane and lifting off. Earhart finished the race at Cleveland, Ohio, in third place.

Earhart continued her racing

and record-breaking career, securing personal satisfaction but also making a major contribution to the further popularization of flying and the role of women in the field.

In 1928 her life was permanently changed by captain H. H. Railey, who had been

asked by George Palmer Putnam, a New York publisher, to find the person to become the

first woman to complete a transatlantic flight. Caught by Earhart's resemblance to Charles

Lindbergh, Railey coined the nickname "Lady Lindy" for Earhart. Just one week later

Earhart and Putnam met in New York, and Putnam quickly decided that Earhart was the

woman for the flight on which she would be a passenger, with the formal designation commander, rather than a real member of the crew as she lacked multiengined and instrument

flying experience.

The task of flying the three-engined Fokker FVII, named Friendship, was entrusted to Wilmer Stultz and Louis Gordon. On June 3,1928, following a delay of several days as the weather improved, the Friendship left for Halifax, Nova Scotia, where adverse weather again imposed a delay to June 18. Flying through dense fog for most of the trip, the Friendship landed at Burry Port in South Wales and not in Ireland, as had been planned. Earhart entered the aviation history books. Earhart entered three Bendix transcontinental air races, and during 1933 took a special prize for the first woman to complete the course. In the early 1930s Earhart also set women's speed and distance records with 181 mph and 2,026.5 miles respectively, and also secured an Autogiro altitude record of 18,415 ft.

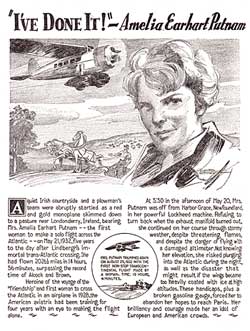

Then on May 21 1932, Earhart entered the "big time" of flying when she completed the first solo flight over the Atlantic by a woman, in the process becoming the first person to have crossed this ocean by air on two occasions. This flight also qualified for two records, for the longest nonstop distance by a woman and for the most rapid crossing. Earhart additionally set and then improved some women's transcontinental speed records, and achieved many point-to-point records.

In 1931 Earhart married Putnam, and after this became a part-time counselor to women students at Perdue University.

On June 1 1937, Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, lilted off from Miami, Florida. in their Lockheed Electra twin-engined mono- plane on a flight round the world. The flight progressed via San Juan in Puerto Rico, the northeast coast of South America, across the Atlantic to Africa and then the Red Sea before progressing to Karachi, Calcutta. Rangoon. Bangkok. Singapore. Bandoeng, Port Darwin, and Lae in New Guinea. This was the last point at which anyone saw Earhart and Noonan, who failed to arrive at their next staging point, Howland Island in the Pacific.

On July, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized a $4-million search by nine ships and 66 aircraft, but this failed to find the Electra or its crew. Many theories about her fate have been advanced over the years, including the suggestion that she was involved in a reconnaissance authorized by Roosevelt to determine Japanese military developments in the Pacific.

It, has also been claimed that she deliberately crashed her Electra into the ocean; that she was captured by the Japanese and forced to broadcast to American GIs as "Tokyo Rose" in World War II: and that she lived for years on an island in the South Pacific with a native fisherman.

More recently, the results of a series of four archaeological expeditions to uninhabited Nikumaroro atoll suggest that Earhart's and Noonan's Electra may have landed there, out of fuel, and that the two perished for lack of water.

|

|

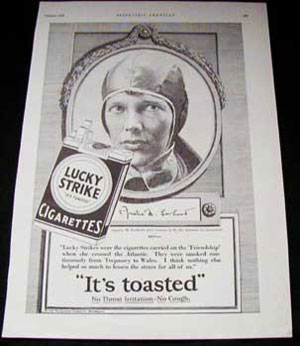

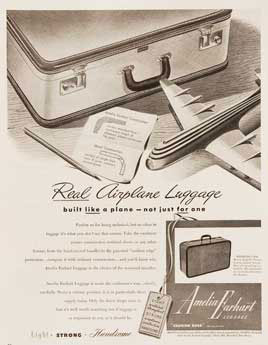

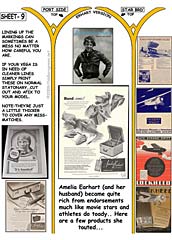

Amelia Earhart's Advertisements from the 1940's. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

These are some images of Amelia Earhart's Lockheed Vega. |

I don’t actually have a question. I just wanted to thank you for the great model of the Lockheed Vega (the plane that Amelia Earhart flew). My 9 yr old daughter is named Amelia after Amelia Earhart and because grandpa was a pilot. Grandpa and my husband built an airplane kit (full size plane that actually flew) together when my husband was in high school. At any rate my daughter dressed as Amelia Earhart to give a book report to her fourth grade class. I downloaded and built the Lockheed Vega for her to use as a prop. It was challenging and took quite a bit of effort on my part. The book report and the model plane were a great success. We are planning on suspending the model from her ceiling eventually. I don’t actually have a question. I just wanted to thank you for the great model of the Lockheed Vega (the plane that Amelia Earhart flew). My 9 yr old daughter is named Amelia after Amelia Earhart and because grandpa was a pilot. Grandpa and my husband built an airplane kit (full size plane that actually flew) together when my husband was in high school. At any rate my daughter dressed as Amelia Earhart to give a book report to her fourth grade class. I downloaded and built the Lockheed Vega for her to use as a prop. It was challenging and took quite a bit of effort on my part. The book report and the model plane were a great success. We are planning on suspending the model from her ceiling eventually.So thanks again for the great model. I have attached a photo of my daughter in costume with the Vega. Carol R |

|

|

Lockheed Marketing Photo Op: Amelia Earhart (rolling a cigarette) & Wiley Post posing for the media |

|

|

|

These beautiful illustrations from 1933 of Amelia Earhart, and Wiley Post come in full size 8.5x11 PDF in your MyModels folder. |

|

|

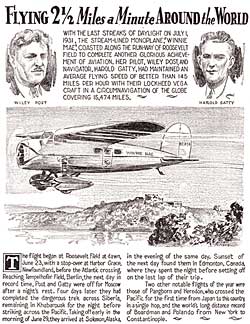

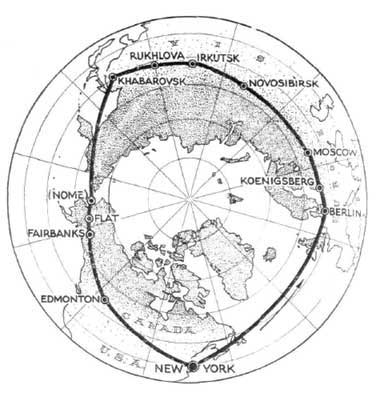

Wiley Post and his Magnificent Winnie Mae Vega: Not willing to rest on his accomplishment, Post set out in 1933 to top his record. Between July 11 and 22, 1933, he flew his Vega 5 Winnie Mae around the world again but this time in seven days 18 hours and 43 minutes. He would have done it faster, but when he landed in Alaska on the last leg, he damaged his propeller and lost seven hours waiting for repairs. Post had not only bested his own record, but in the process, he also became the first person to fly around the world solo. Pilot Wiley Post later flew it to altitude record of 55,000 feet. Ground speed of 340 mph at that height suggests that he was first aviator to fly a jet stream. |

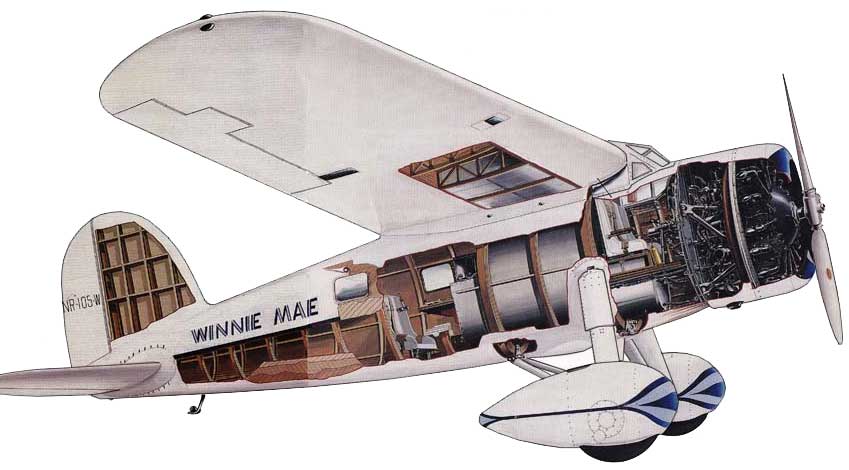

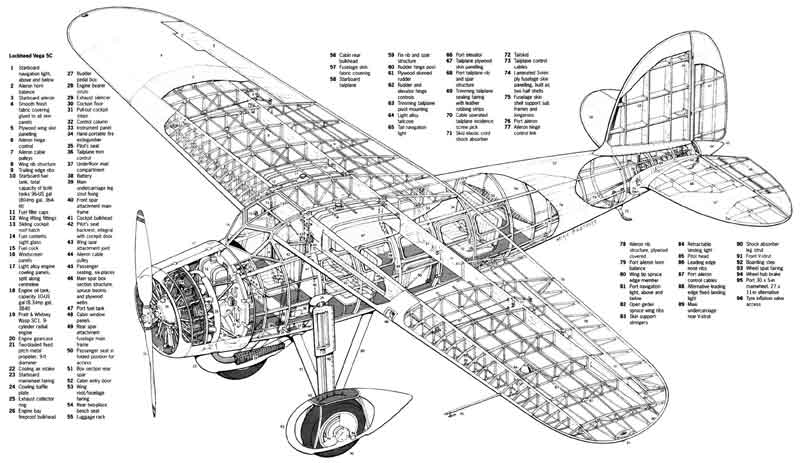

The Lockheed Vega Winnie Mae (cutaway) flown by Wiley Post which set round-the-world speed record in 1931. |

|

|

Painted on the side of Winnie Mae, are Wiley Post's stops on his around the world solo flights. |

This is a map (right) of Wiley Post's stops on his second round the world trip.  |

|

|

Natives of Flat, Alaska, helping right Wiley Post's plane, the Winnie Mae, after Post had nosed over in a cross wind July 20 after being in the air 22 hours and 32 minutes on his flight from Khabarovsk, Siberia. The only damage was a broken propeller, and a new one was brought to Flat by Joe Crosson, pioneer Alaska flier. The new propeller installed, Post continued his flight to Fairbanks. |

Wiley Post & Will Rogers Their Last Flight

In 1932 Post met the famous humorist (and fellow Oklahoman) Will Rogers and the two became close friends. Rogers often flew with Post as a passenger and he contributed an introduction to the book Post had done with Gatty about their flight. In 1935, looking for new material for his newspaper column, Rogers asked Post if they could fly to Alaska.

The Lockheed-Orion Model 9E Special, formerly owned by TWA, that was modified by Wiley Post for his trip to Alaska. Among other modifications, Post replaced the engine with a 550 horsepower type, installed a three-bladed variable pitch propeller, swapped out the wing with one that was six feet longer from a Lockheed-Explorer Model 7 Special, that had fixed landing gear. It is interesting to note

that the modified Orion was more like an Altair than an Orion. Lockheed built

these aircraft with interchangeable parts and several were actually hybrids.

Post went to Lockheed and asked the engineers to add pontoons to the Orion-Explorer aircraft, but they refused, telling him that pontoons would upset the aerodynamic of the plane. Post (believing -Rogers’ weight would compensate) had pontoons placed on the plane himself and flew Rogers up to Alaska. On August 15, 1935 the fears of the Lockheed engineers were realized and the plane stalled while taking off from a lake near Point Barrow. Post and Rogers died in the crash sending the nation into mourning for two of its most popular cultural heroes.

|

|

Maybe he should have been taking a field sobriety test because of his thinking of modifying an aircraft with modifications that Lockheed engineers had refused to make. |

Last photo taken of Wiley Post and Will Rogers, only hours before their fatal crash. |

|

|

Wiley Post and Amelia Earhart cutouts come with the model folder! |

|

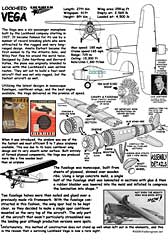

About the Lockheed Vega

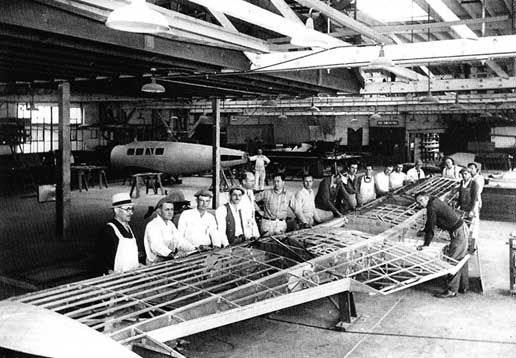

Allen and Malcolm Loughhead (pronounced Lockheed) first began building airplanes in San Francisco in 1916, but their company folded in l92l. In December 1926, the brothers resurfaced in Hollywood, California, with new investors, to form the Lockheed Aircraft Company.

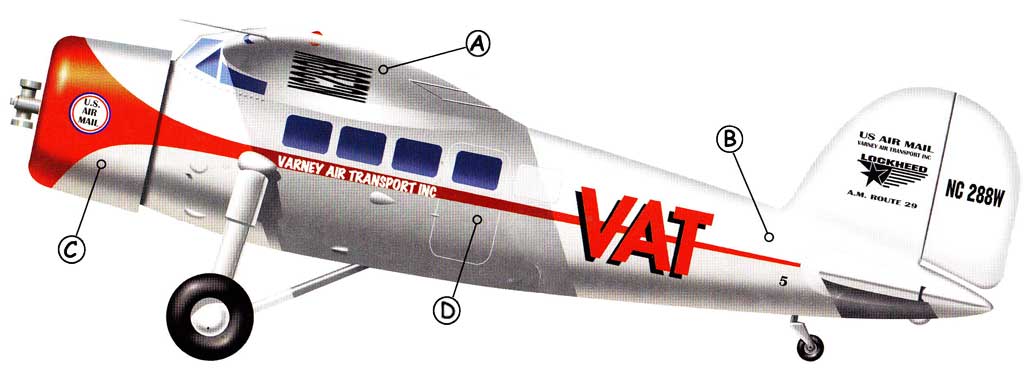

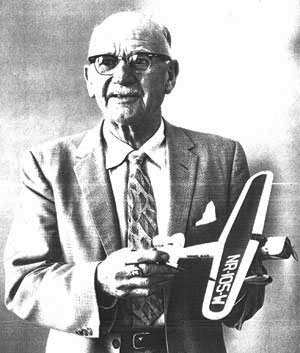

The first product was the Vega, a high-wing monoplane designed by an up-and-coming young airplane designer named John K. Northrop. (image below-more about him later). The four-passenger Vega was one of the first important and successful American commercial transports, and it marked the beginning of one of the world's most important aircraft makers.

The aircraft was named for the fifth brightest star visible from the Earth, setting for Lockheed the tradition of naming aircraft after stars and other astronomical features. Though the prototype Vega-the Golden Eagle flown by Jack Frost-was lost in the infamous Dole Derby race from California to Hawaii in August 1927, the Vega attracted a good deal of interest from pilots intent on endurance flights and later from commercial airlines.

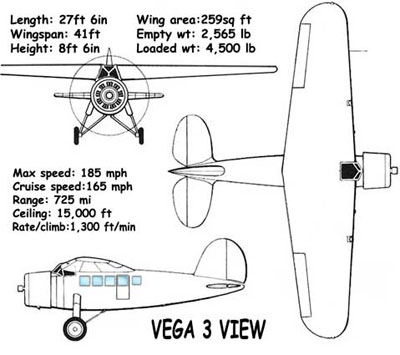

Meanwhile, the original four-passenger Vega 1 evolved into the much more capable Lockheed Model 5, or Vega J. The Vega 1 had a wingspan of 4l feet and a length of 27 feet 6 inches. It weighed 2,900 pounds fully loaded and fueled and had a service ceiling of 15,000 feet. It was powered by a single 225-horsepower air-cooled nine cylinder Wright whirlwind J-5 engine that gave it a cruising speed of 118 miles per hour and a range of 900 miles. The Vega 5 had the same dimensions as the Vega I and had a gross weight of 4,265 pounds. it was powered by a single 450-horsepower, air cooled Pratt & Whitney R-1340 Wasp engine that gave it a cruising speed of 155 miles per hour.

Captain George Hubert

The flight of Wilkins and Eilson was a miraculous combination of navigational skill, bravado, and plain luck, and it made the Vega. The company was deluged with orders. The backlog soon totaled more than a quarter of a million dollars. This was not enough to hold Jack Northrop, who wanted to move on to metal construction. He left and was replaced as chief engineer by Gerry Vultee (who was also to start his own airplane company in time). |

Even as Wiley Post was chalking up accomplishments in the Winnie Mae, others were setting new records in their Vegas. These daredevil aviators included Amelia Earhart, Jimmie Mattern, Ruth Nichols, and Roscoe Turner. Known as "The Flying Debutante," Ruth Nichols set both transcontinental endurance and altitude (28,743 feet) records in her Vega, while Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly the Atlantic solo. Earhart's Atlantic flight is a testimony to the Vega's durability. She landed in Ireland on May 21, 1932, after a flight of 14 hours 54 minutes. During this flight, her Vega suffered severe icing while trying to climb over a weather front and went into a 3,000-foot plunge from which Earhart was able to recover.

Even as Wiley Post was chalking up accomplishments in the Winnie Mae, others were setting new records in their Vegas. These daredevil aviators included Amelia Earhart, Jimmie Mattern, Ruth Nichols, and Roscoe Turner. Known as "The Flying Debutante," Ruth Nichols set both transcontinental endurance and altitude (28,743 feet) records in her Vega, while Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly the Atlantic solo. Earhart's Atlantic flight is a testimony to the Vega's durability. She landed in Ireland on May 21, 1932, after a flight of 14 hours 54 minutes. During this flight, her Vega suffered severe icing while trying to climb over a weather front and went into a 3,000-foot plunge from which Earhart was able to recover.

Eventually, over 128 Vegas were built, including the Model 4 Air Express, which was built for Western Air Express (later known as Western Airlines) and for the Texaco Oil Company. Though the two aircraft were similar, the Model 4 Air Express differed from the Vega in that it had a parasol wing and the pilot was positioned in an open cockpit behind the passenger cabin.

The Lockheed Sirius, Altair, and Orion were the successors to the Vega throughout the early 1930s. They were in the same size and weight class as the Vega, and like the Vega, they were powered by single radial engines. These were low-wing aircraft, and the Altair and Orion had retractable landing gear. Just as they had done with the Vega, many important pilots of the era flew her low-wing sisters.

Charles Lindbergh operated a Sirius, and Jimmy Doolittle flew an Orion for the Shell Oil Company.

Lockheed Company Background:

Lockheed Martin Corporation was formed in March 1995 with the merger of two of the world's premier technology companies, Lockheed Corporation and Martin Marietta Corporation. In 1996, Lockheed Martin completed its strategic combination with the defense electronics and systems integration businesses of Loral.

Lockheed Martin traces its roots back to the early days of flight. In 1909 aviation pioneer Glenn L. Martin organized a company around a modest airplane construction business and built it into a major airframe supplier to U.S. military and commercial customers. Martin Marietta was established in 1961 when the Glenn L. Martin Company merged with American-Marietta Corp., a leading supplier of building and road construction materials. In 1913, Allan and Malcolm Loughead (name later changed to Lockheed) flew the first Lockheed plane over San Francisco Bay. The modern Lockheed Corporation was formed in 1932 after the fledgling airplane company was reorganized.

His mother was a well-known novelist and journalist. She raised her two boys on a small ranch after separating from her husband. The boys attended elementary school only, but were ardently mechanically inclined from an early age. Allan became an automobile mechanic in San Francisco and by 1909 was driving race cars.

How did Allan get into aviation? He had an older, half-brother named Victor who was an engineer in Chicago with an early aviation firm. That firm negotiated rights to manufacture and distribute the Montgomery Glider (the parent company was a San Francisco organization). Through Victor, the Lockheed brothers got involved with installing a 2-cylinder, 12 HP motor on the glider with Victor acting as engineer. Allan, without any flying experience, soloed this airplane on a dare at the Hawthorne Race Track in Chicago in December, 1910. And so his career in aviation began.

The first plane to bear the Lockheed name was built by Allan and Malcolm in San Francisco in 1913. It was a seaplane, the “Model G”, used by the brothers to take persons on flights for $10 an hour.

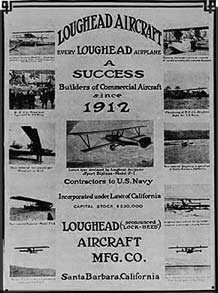

The brothers moved to Santa Barbara in 1915 and formed the Loughead Aircraft Manufacturing Company. The firm won contracts for military seaplanes during WWI –some of the first awarded – but after the war the company floundered. Malcolm left in 1919 to pursue hydraulic automobile brakes, but Allan persevered.

As a post-war effort, and just before Malcolm left, they linked up with Antony Stadlman (an Early Bird colleague from Chicago) and John K. Northrop. They designed and built a novel sport biplane, called the S-1, for the commercial market. It was tested successfully at Redwood City, CA in 1919 by Gilbert Budwig and flew well. In competition with WWI surplus planes, the S-1 did not sell well, however, and the project was dropped.

As a post-war effort, and just before Malcolm left, they linked up with Antony Stadlman (an Early Bird colleague from Chicago) and John K. Northrop. They designed and built a novel sport biplane, called the S-1, for the commercial market. It was tested successfully at Redwood City, CA in 1919 by Gilbert Budwig and flew well. In competition with WWI surplus planes, the S-1 did not sell well, however, and the project was dropped.

Interestingly, Malcolm formed the Lockheed Hydraulic Brake Company and moved to Detroit. He succeeded in working with Walter Chrysler to introduce hydraulic brakes on his 1924 automobiles. Malcolm sold his business to Bendix in 1932.

Meanwhile, in California, the Lockheed aircraft project went out of business in 1921. Allan went into real estate and became the west coast representative for Malcolm’s brakes. With new financial backers Allan reformed the company in Hollywood during 1926. Stadlman and Northrop returned to work with him and their first airplane out the door was the famous, advanced design Lockheed Vega.

They were three brothers, born Loughead, an Irish name which is properly pronounced something like Lockheed. (After half a lifetime of being miscalled Log-head, they bowed to the inevitable and decided to spell it like it is.)

Their mother, Mrs. Loughead, was on her own, maintaining a modest place on the shores of San Francisco Bay. She supported her four children (there was a sister, too) by selling feature articles to the San Francisco Chronicle, and grapes and prunes from her groves to all comers. But fruit held no fascination for her sons, nor feature writing, either. They all wanted ,to be engineers. Victor, the eldest, departed first, migrating to Chicago to be an automobile engineer. Malcolm got a job in 1904 as a mechanic for White steam cars. The youngest, Allan, was still a kid when he was hired as a solderer in a repair shop. Before long Allan followed Victor to Chicago to work as a mechanic for Victor's boss, a truck and automobile distributor who dabbled in aviation on the side.

Allan was fascinated. In 1910 his boss bought a Curtiss Pusher, but neither of the two appointed pilots could get it airborne. Allan did by then have a few minutes of copilot time, and talked his way into being allowed a try. "I've got a twenty-dollar gold piece that says I'll make it fly," he boldly announced, but such was his confidence that there were no takers, even at three to one. He did indeed get the Curtiss up and down, whole and in one piece. "Now I was an aviator," he later announced. Aviation in 1910 meant barnstorming, and that was how Allan Loughead aviated until one wet September day in 1911 , when he tried to take off in a Curtiss that was sodden with rain.

"AVIATOR IN GREAT PERIL"

was how the local paper headlined the crash. "Aviator Loughead has miraculous escape from death" was the newspaper's opinion.

Aviator Loughead evidently agreed, for he returned home to San Francisco with a midwestern bride, and became once more a mechanic. But that was not all; on the side, together with brother Malcolm, he designed and built a small seaplane. It was called the Model G, for no better reason than that the Loughead brothers wished the purchasing public to think that all the previous experience of building models A through F had gone into it. For eighteen months they planed and glued and stitched away at their creation, a conventional biplane of its era, with a cruciform tail hinged on a universal joint, and an 80-hp Curtiss OX driving a Tractor propeller. The Model G first flew (Allan piloting, recovered from his previous funk) on June 15, 1913, and it flew well, in spite of grossly oversensitive controls due to that all moving tail.

In 1915, when the Panama-Pacific Exposition opened in San Francisco, the Loughead brothers finally saw a chance to make some money with their own seaplane. In fifty days of hopping passengers they made $6,000. Emboldened by success, they next formed the Loughead Aircraft Manufacturing Company, and set to designing and building a monster twin-engined ten seat flying boat. They hired a likely lad who was always in and out of their shop-a garage mechanic named Jack Northrop-to do some stress analysis and help with shaping the hull. This new seaplane flew strongly, and the Lougheads had hopes of selling it to the Navy. But when America entered the war, the Navy decided on a policy of standardization, and the Loughead F-l seaplane wasn't to be the standard. The Curtiss seaplane was. The Lougheads next rigged the F-1 as a land plane, and tried flying it to Washington as a demonstration of its excellence. After it ended up on its nose in Arizona, they took it back to California where they flew passengers, and also movie cameramen who gladly paid $150 an hour for flying time whenever aerial footage was needed.

Their next air craft was a beauty: a biplane with a single-seat and cigar-shaped fuselage, neatly tapered wings, and a 25-hp two-cylinder engine of Loughead design. The S-1 would do 70 mph and land at 25 mph, and it had folding wings so it would fit in any garage. For 1919 it was an advanced design, but, with that fleet of cheap surplus Jennies available, nobody wanted it. The S-1 cost $30,000 to develop, and not one was ever sold.

Malcolm Loughead had long held the idea that he could build a four-wheel hydraulic brake system for automobiles. "Keep at it," Allan told him, with classic understatement. "It's a million-dollar idea." So, in 1921, they liquidated Loughead Aircraft. Malcolm went of to Detroit to develop hydraulic brakes-using for the first time the phonetic name Lockheed. Allan, meanwhile, sold real estate in Los Angeles and later became a regional distributor for Lockheed brakes. But in spare moments he and Jack Northrop, now working for Donald Douglas, would meet to work on the design of an all plywood monoplane. In 1926, they drew up a stock prospectus for a new company and showed it to a wealthy brick and tile manufacturer named Kenneth Jay. Jay took one look at the drawings of their streamlined monoplane and offered to put up all the $25,000 they were asking, in return for fifty-one percent of the common stock and all of the preferred. But he insisted the company be called Lockheed, to capitalize on the growing success of brother Malcolm's brakes.

They called the plane the Vega, a simple name that connoted astronomical speed and distance. They built the first Vega for a grand total of $17,500, including machine tools. The biggest cost was the Wright Whirlwind engine. For 1926, the Vega was an astonishingly futuristic airplane. It had the same cigar-shaped, plywood fuselage as the unsuccessful S-1, but this fuselage was hung from a beautiful, one-piece tapered wing which was so clean it didn't even have a bracing strut.

They called the plane the Vega, a simple name that connoted astronomical speed and distance. They built the first Vega for a grand total of $17,500, including machine tools. The biggest cost was the Wright Whirlwind engine. For 1926, the Vega was an astonishingly futuristic airplane. It had the same cigar-shaped, plywood fuselage as the unsuccessful S-1, but this fuselage was hung from a beautiful, one-piece tapered wing which was so clean it didn't even have a bracing strut.

The Vega's timing was uncannily good, too. Just as the factory was putting the finishing touches to it came the furor over Lindbergh's flight to Paris and the wild boom in aviation that followed.

Lockheed's first Vega made its maiden flight on July 4, 1927. Before the month was out the company had a purchaser for the airplane-George Hearst of the newspaper empire. A pineapple millionaire from Hawaii named Jim Dole had put up $35,000 in prize money for an air race from California to Hawaii and Hearst wanted to enter the Vega. Dubbed the Golden Eagle, and carrying two pilots, it was one of four entrants to set off from Oakland on August 16, I927. It was never seen again. However, in its brief lifetime the Golden Eagle had made a profound impression on many people, notably on an Australian adventurer named Hubert Wilkins, who'd seen its slippery lines flash past the window of his hotel room in San Francisco.

Among the customers who came knocking, early in 1928, were officials of Western Air Express, who wondered whether Lockheed could increase the Vega's power and speed. Oh, and one other thing: Everybody knew no airline pilot could do a proper job without the wind on his cheek. Could Lockheed please give its plane an open cockpit? :))

Lockheed met the first request by substituting a 450-hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp for the old 220 Whirlwind. Because of the Wasp's powerful slipstream, fulfilling the second request meant moving the pilot from his usual position in a Vega, right behind the engine, to a newly fashioned cockpit in the rear fuselage, just ahead of the vertical stabilizer. To allow the poor goggled pilot to see anything forward, the wing had to be jacked up on stilts above the fuselage. The resulting airplane, called the Air Express, was ugly but it did go. With a 150-mph cruise it outran the Vega by 35 mph.

One Lockheed pilot who earned undying fame was the one-eyed oil field roustabout Wiley Post. Post flew a splendid blue and white Vega named the Winnie Mae in honor of the daughter of his boss, F. C. Hall. In 1931, Post, who had never crossed any body of water larger than Long Island Sound, set off on a flight around the world. He took with him a navigator named Harold Gatty who, like Hubert Wilkins, was an Australian. Gatty's six-month intensive preparation for the flight played a large part in its successful completion. Their time for the trip was under nine days. Two years later, Post was off again, solo this time, but with one of Lawrence Sperry's first autopilots to help him. He began the trip by flying nonstop from New York to Berlin in 25 hours, 45 minutes, and went through some notable adventures, including having the  autopilot twice go out on him. He achieved the almost unbelievable feat of beating by 21 hours solo the around-the-world record he had previously made with a navigator along for aid and assistance.

autopilot twice go out on him. He achieved the almost unbelievable feat of beating by 21 hours solo the around-the-world record he had previously made with a navigator along for aid and assistance.

Later, Wiley Post was fascinated by the prospects of flight in the stratosphere, and had Goodrich build him a pressure suit. Post added supercharging and a droppable landing gear to the Winnie Mae and achieved an altitude of' 55,000 feet and speeds of up to 340 mph. High-flying Wiley was perhaps the first pilot to chance upon a jet stream. Another extravagantly colorful Lockheed pilot was Roscoe Turner, a dandy who often flew with a lion cub (with its own parachute) for passenger.

Lockheed made several low-wing variants on the same basic design. There was the Explorer, which evolved into the Sirius, an open-cockpit airplane designed by Gerry Vultee to Charles Lindbergh's specifications. Lindbergh spent all his time in the Lockheed factory while the plane was a-building, much as he had done earlier at Ryan. He and his bride Anne Morrow flew the equivalent of several times around the world in this Sirius, prospecting air routes for Pan American, before the airplane was wrecked while being loaded onto a ship in China.

After the Sirius came the Altair, which had a hand-wound retractable gear and the same 450-hp Wasp that powered most of its predecessors; it could hit 230 mph. The last of the wooden Lockheeds was the Orion, which featured the first successful hydraulic retractable landing gear. With a 650-hp Wright Cyclone engine, it could cruise, with six passengers, at 200 mph, Prices varied from $13,500 in 1928 for a regular Vega, to $25,000 for a 1931 Orion. Far more Vegas were built than any of the other variants. Less than two hundred of all models were ever built.

The Lockheed company proved weaker than the airplanes it built. In 1929, the company was sold to that ill-timed and ill-conceived corporation, Detroit Aircraft, which was meant to be a General Motors of the air. Allan Lockheed warned against the deal. "Out of the group that ultimately made up the Detroit Aircraft family," he said, "our company alone had any degree of financial stability. I was certain only tragedy could come out of the proposed sale." But he didn't own a controlling interest and he was outvoted. He resigned, and sold his shares for $23 each. Detroit Aircraft lost $733,000 that year, and its own shares went from $15 to 12 1/2 cents in two years. In 1932, the Lockheed company was sold, for $40,000, to the only bidders, a group headed by Robert E. Gross, which still runs Lockheed today.

Of the 197 wooden Lockheeds that were built, only about a dozen survive. Most of the others were simply cracked up at one time or another. In the mid-thirties, as the airlines modernized, they sold their old wooden planes off to little transport companies in places like Mexico and Alaska, where short runways and the difficult climate or topography got them in the end. The retractable-gear Orions and Altairs often perished when the gear jammed in the up or half-up position. After 1936, large numbers of Lockheeds were smuggled across to Spain by the Republicans and later vanished in the debris of the civil war. One Vega is still privately owned, having been put out to grass after years of use in experiments by the military to see if a wooden airplane could be made transparent to radar. Lindbergh's Tingmissartoq is in Washington, and Wiley Post's Winnie Mae, the most magnificent Lockheed of them all, hangs proudly in the Smithsonian Institution.

|

|

|

|

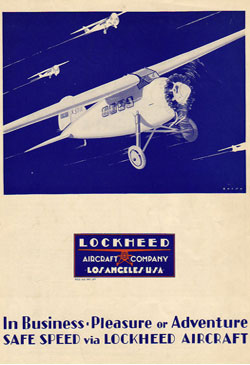

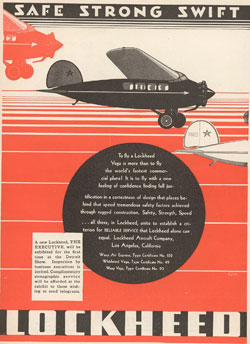

Lockheed did a pretty good graphical job of marketing their products as seen here with these 1920s-1930s posters. Lockheed had rolled out just three airplanes in 1927. Production the next year was sixty-four planes and sales were over $750,000. "It takes a Lockheed to beat a Lockheed" was the upcoming company's slogan; "Lockheed aircraft will carry the same payload farther, faster, and with less fuel expenditure," which about summed it up. The airlines became major customers for the planes and almost every speed king of the day flew Lockheed. |

|

|

|||

|

|

||

Loughead F-l seaplane. |

Loughead S-1. |

||

|

Specifications Performance Note: The three view (left) is to be taken with a grain of salt regarding accuracy. |

|

|||

| A: Exceptionally strong wing construction was the feature of the Vega. The wings were internally braced, removing the need for struts, and of cantilever design. | B: Lockheed's wooded monocoque construction methods were pioneered by company designer Jack Northrop (later a manufacturer in his own right). | C: Vegas were fitted with a wide variety of engines. As the aircraft grew in size and capacity, more horsepower was required. Most engines were conventional radial designs, although at least once airframe was fitted with a diesel motor. | D: Most early Vegas were initially equipped to carry four passengers, though airlines made their own modifications. This aircraft and others in the Varney fleet were able to hold nine people. More powerful engines were fitted to cope with the extra weight. |

|

|

The structure of these Lockheed Vegas was a true masterpiece of the cabinetmaker's art. The fuselage was built in two halves inside a concrete mold which was first lined with goreshaped, tapered strips of veneer. The inner surface was then liberally sloshed with casein glue, every man jack in the factory being called in to wield a pot and a brush. Then a cross-layer of birch veneer was laid on, followed by more glue, and another longitudinal layer to form the third ply. A rubber air bag was placed on top, a cover was bolted on, and the air bag inflated to apply an even pressure of twenty pounds per square inch while the glue cured. The fuselage design was never pure monocoque, for a sturdy wooden skeleton of longerons and ring formers was built, to which the two outer half-shells were later tacked and glued. Cutouts for doors, windows, and cockpits were easily made, and the piece of three-ply sawed for the door was later made into the door itself. The beautiful, thick, tapered wings were more orthodox, with long tapered spars, and ribs built up of strips, with a kind of Pratt truss used to maintain the airfoil. The whole wing was covered with birch veneer plywood. |

|

|

|

This highly detailed Vega cutaway comes in 8.5 x 11 PDF for FREE included in your MyModels folder! |

Cutout of Amelia included with model VEGA |

-Vega.jpg) |

|

These two photos above were of Dick Dolls beta build of the Earhart Lockheed Vega. Look how much the plastic prop disc looks when posed as a flying model. He emails: Finished the Vega but wasted a few days sending email, waiting for weather to break to take photos. Well "it ain't my purtiest work" ( my doing), but I got it done. |

|

|

downloadable-cardmodel.jpg) |

The three images above are From Dr John Glessner who reduced the regular version to 1:72 scale |

Wilkins was a man obsessed by polar exploration. He dreamed of flying clear across the Arctic Sea and had wrecked several lesser airplanes trying. Wilkins bought the second Vega, had it fitted with extra tanks, set on skis, and flown to Alaska by his friend Ben Eilson. On April 15, 1928, they left Point Barrow for Spitzbergen, 2,200 miles away across a wilderness of ice. After more than twenty hours of flying they put down in a blizzard and sat for five days in the plane, shivering and hoping their emergency rations would last. Then, with Wilkins pushing and heaving to free the stuck skis, they tried to take off. Each time Wilkins would lose his hold on the Vega, so that Eilson was forced to put down again. Finally, down to ten gallons of gas, they were airborne together and in only five miles they came to the Norwegian settlement they had been aiming for.

Wilkins was a man obsessed by polar exploration. He dreamed of flying clear across the Arctic Sea and had wrecked several lesser airplanes trying. Wilkins bought the second Vega, had it fitted with extra tanks, set on skis, and flown to Alaska by his friend Ben Eilson. On April 15, 1928, they left Point Barrow for Spitzbergen, 2,200 miles away across a wilderness of ice. After more than twenty hours of flying they put down in a blizzard and sat for five days in the plane, shivering and hoping their emergency rations would last. Then, with Wilkins pushing and heaving to free the stuck skis, they tried to take off. Each time Wilkins would lose his hold on the Vega, so that Eilson was forced to put down again. Finally, down to ten gallons of gas, they were airborne together and in only five miles they came to the Norwegian settlement they had been aiming for.

engine. John made his own wheels for his Vega model:

engine. John made his own wheels for his Vega model: