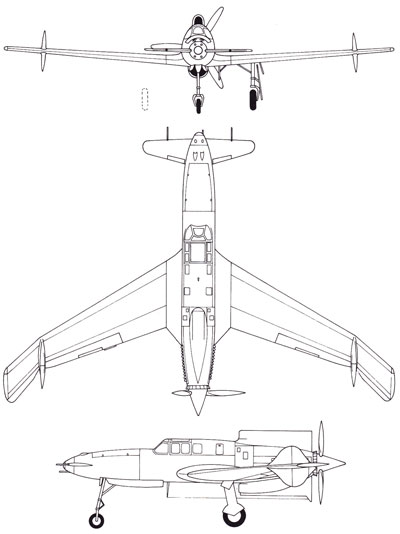

Curtiss XP-55 Ascender

Resulting, like the Vultee XP-54 and Northrop XP-56, from a 1940 competition for 'unconventional' fighter designs, the XP-55 was built with a pusher prop, highly swept wings and a canard foreplane. Named 'Ascender' by Curtiss, this title was often corrupted to 'Ass-ender' due to its backwards-facing appearance. Designed around the Pratt & Whitney X-1800 engine, the cancellation of this project led to the fitting of a standard Allison V-1710. Not surprisingly for such an unusual configuration, the XP-55 suffered stability problems, and all flying surfaces were enlarged at one time or another in an attempt to cure these. Until the canard foreplane was modified the XP-55 showed a marked reluctance to leave the ground at all. Four Ascenders were built, of which two crashed, killing one of the pilots and an unfortunate passerby.

Both crashes were the result of the Ascender's vicious stall characteristics. Even though an early form of stall warning was fitted to the aircraft, most of the pilots who flew it considered the XP-55 to be very dangerous, with extremely poor handling characteristics. A great deal of trouble was also caused by the rear-mounted powerplant; many problems were encountered with engine cooling, resulting in the engine temperature nearly always being in the red danger zone.

Curtiss Ascender XP-55

The tail-first Curtiss XP-55 was certainly one of the most novel American fighters to actually be constructed, although the canard configuration was far from new. It will be recalled that the Wright Flyer of 1903 was constructed in the same manner, but it was unusual to see such a design on a modern, high performance aircraft.

The tail-first Curtiss XP-55 was certainly one of the most novel American fighters to actually be constructed, although the canard configuration was far from new. It will be recalled that the Wright Flyer of 1903 was constructed in the same manner, but it was unusual to see such a design on a modern, high performance aircraft.

The XP-55, Curtiss Model 24, was the second type selected by the Army for the 1939 specifications for unorthodox designs. A request for specific engineering data was received by Curtiss on June 22, 1940. Results of wind tunnel testing did not satisfy the Army, so Curtiss constructed a full-size flying model to evaluate the radical layout. The model was successfully flown 169 times at Muroc, California. The flight tests did indicate several areas requiring improvements, mainly in vertical keel area, but the Army was satisfied with the potential of the design and approved construction of three XP-55's on July 10, 1942. Originally intending to use the Pratt & Whitney X-1800 engine, an Allison V- 1710-F16 was substituted when the P & W engine was cancelled. Because of the pusher arrangement of the engine, it was necessary to devise a means of jettisoning the propeller in the event of an emergency bailout.

The first XP-55, now named Ascender, was ready for flight testing on July 13, 1943. The initial take-off run was so long that the nose elevator area was increased fifteen percent for subsequent flights, and the ailerons were trimmed upward when the flaps were lowered.

On November 15, 1943, the XP-55 flipped onto its back during stall tests and attempts to recover failed. The plane stabilized in the inverted state but the engine quit and the XP-55 fell vertically 16,000 feet before the pilot decided an inverted landing would ruin his whole day and safely abandoned the stricken machine. The possibility of this condition had been predicted by the early wind-tunnel tests, and now it was necessary to correct the design. The second Ascender was nearing completion and flight testing was resumed when it was available, but stalls were restricted. The third XP-55 did incorporate the necessary revisions. These included extended wingtips with small additional "trailerons" outboard of the wing-mounted rudders.

The Ascender displayed satisfactory handling characteristics during normal flight, but at low speeds, it became overly sensitive; and, even after modifications, the stall was quite an experience. Engine cooling was inadequate and some stability problems remained, when the Army decided the unorthodox little fighter would not be an effective weapon.

The XP-55 was not a true canard since it lacked a fixed forward elevator. The entire surface was movable and trailed in normal flight. In effect, it was a flying wing with a forward trimming surface. Performance of the XP-55 was similar to many conventional fighters, having a top speed of 390 mph at 19,300 feet. Service ceiling was 34,600 feet, and it could reach 20,000 feet in 7.1 minutes. The swept-wing of the third XP-55 spanned 44 feet 6 inches, length was 29 feet 7 inches, height was 10 feet, and wing area was 235 sq. feet. Fuel capacity was 110 gallons. Empty and gross weights were 6,354 pounds and 7,330 pounds. Four .50 cal. M2 machine guns were located in the nose, each gun having 250 rounds.

An example of the XP-55 Ascender has been preserved by the Smithsonian Institution for display in the National Aerospace Museum.

This was one of the last Curtiss projects to be supervised by Donovan A. Berlin, who left to join Fisher before the outcome of the XP-55 submission was known, leaving George Augustus Page Jr. and E. M. Bud Flesh in charge of the design team.

This was one of the last Curtiss projects to be supervised by Donovan A. Berlin, who left to join Fisher before the outcome of the XP-55 submission was known, leaving George Augustus Page Jr. and E. M. Bud Flesh in charge of the design team.

On November 27, 1939 the USAAC had announced a competition for a very high performance fighter, the emphasis being placed on low drag, good visibility for the pilot and armament to the standard of contemporary European fighters. Nine companies submitted designs but only three were selected to develop their projects further, all being for unorthodox designs with pusher propellers: these were the Vultee XP-54 (q.v.), the Curtiss XP-55 and the Northrop XP-56 (q.v.)

The XP-55 design was for a metal fuselage with four machine guns in the nose and the engine in the extreme rear of the fuselage, envisaging use of the liquid-cooled Pratt & Whitney X-1800-A3 G engine. The cantilever, laminar flow wings were "swept" and were equipped with ailerons and flaps on the trailing edge as well as directional fins and rudders near the wing tips, above and below the airfoil. The elevators were located near the front of the nose in a horizontal surface. The design was reminiscent of the canard type design formula used in some of the earliest flying machines. For the first time in a Curtiss fighter, the plane was equipped with a tricycle, completely retractable landing gear.

The USAAF was somewhat taken aback by this submission but nevertheless signed a contract for an option to buy on June 22, 1940, which meant that Curtiss was to finance construction of a full scale lightweight model (metal and wood structure with fabric covering) powered by a 275hp Menasco C-65-5 engine; the first flight took place on December 2, 1941 and a speed of 180mph was reached.

This model underwent 169 test flights without revealing any insuperable faults and on July 10, 1942 the USAAF ordered three prototypes. The 2,200hp Pratt & Whitney engine was not available, however, and a 1,275hp Allison V-1710-95 engine had to be installed instead which could certainly not be expected to power the plane to its originally projected speed of 507mph. J. Harvey Gray, Curtiss' test pilot, was at the controls for the plane's first test flight on July 19, 1943 and the test program continued until November 15, on that day Gray had to bail out of the aircraft when it went out of control and crashed.

A number of modifications were made to the second and third prototypes (which had their maiden flights on January 9 and April 25, 1944) aimed at improving directional stability and the efficacy of the elevators but the aircraft was not only slower than design specification, the engine also tended to overheat and the plane handled badly at low speeds and during landing.

Had more traditional fighters such as the P-51 and the P-47 not already proved that they were world beaters, the XP-55 might, perhaps, have had a future, but by 1944 jet propulsion was already forming part of the military's plans and the USAAF chose to abandon the project.

|

Cockpit of the Curtiss XP-55 Ascender. |

Specifications for the Curtiss XP-55 Ascender

|

Length: 29 ft 7 in Wingspan: 40 ft 7 in Height: 10 ft Wing area: 235 ft² Empty weight: 6,354 lb Loaded weight: 7,710 lb Max takeoff weight: 7,930 lb Powerplant: 1× Allison V-1710-95 liquid-cooled V12 engine, 1,275 hp Performance Maximum speed: 390 mph at 19,300 ft Service ceiling: 34,600 ft Armament 4x0.50-inch machine guns in the nose |

|

||

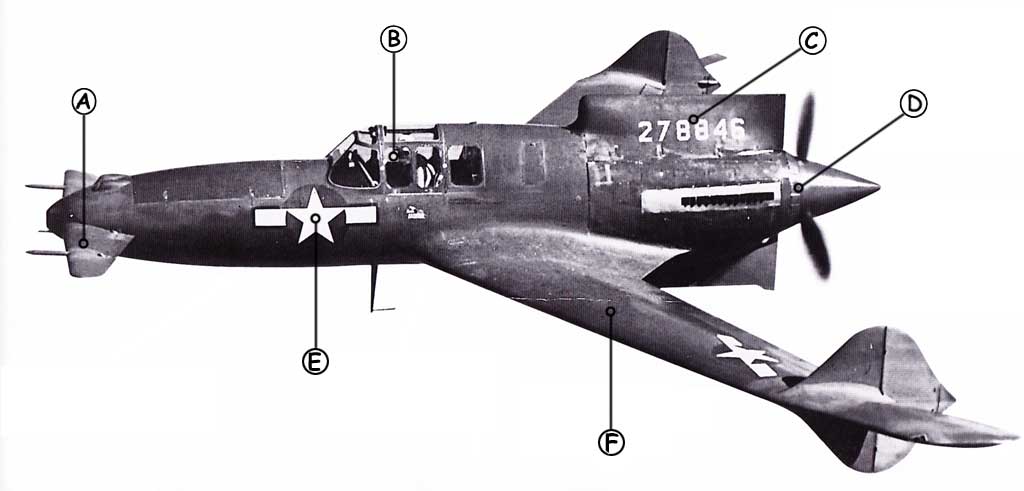

| A: The foreplane was not a canard in the true sense, but a free floating surface with no fixed stabilizer. | B: Entry to the cockpit was said by test pilots to be rather awkward, requiring a telescoping ladder that was stored behind the pilot's seat. | C: One of the XP-55 prototypes, serial number 42-78846, may be seen in the National Air and Space Museum, Washington D.C. |

| D: Because of the engine location, cooling was critical and the engine could easily overheat if taxiing time was not kept to a minimum. | E: The unconventional layout caused bad stall characteristics, with little stall warning and excessive altitude needed for recovery. | F: The XP-55 was essentially a flying wing, having only vestigial vertical surfaces, which were distributed on the rear fuselage and outer wings. |